Eduardo Gudiño Kieffer

Selected stories from

Fabulario (1969) (II)

Link to part I:

E. Gudiño Kieffer: Selected stories from “Fabulario” (1969) (I)

Link to my commentary on the translation:

Commentary on the translation of “Fabulario”, E. Gudiño Kieffer

Eduardo Gudiño Kieffer

Herein you shall find the stories I chose in their original language, followed in each case by my translation into English. I would specially like to thank translator and professor Magalí Libardi for her help in revising my translations. I recommend visiting her excellent and most interesting blog, Nota del traductor.

Fabulario

Castillo

Rompiendo fantasmagóricamente la mansa línea del horizonte, todo el paisaje adherido a sus flancos, el castillo vigilaba con gesto espectral las míseras casas arrebujadas al pie del alcor. Desde la torre de homenaje, rampante sobre la roca abrupta, se divisaba el campo alucinado por el elemental poder de una naturaleza ocre y amarilla como la misma muerte. Por las noches, el viento jugaba entre las almenas, se recataba en los patios abandonados, ceñía los muros verticales con manos invisibles, se deslizaba locamente por las rampas o suspiraba en cada barbacana. El castillo permanecía inmóvil, manteniendo siempre su enorme gesto melodramático, su sonambulesca mudez de piedra, su altanero ademán. Pero le gustaba que el viento lo envolviera en gritos ululantes o en torvas charlas de brujas. El viento era lo único que mantenía aún nobleza, esa nobleza guerrera, empenachada de ideas de honor y de heroísmo, completamente ajena a la domesticidad de este siglo sin Lancelotes ni Bradamantes. El viento era leal y capaz de habitar lo inhabitable, de decir lo indecible. ¡Lo indecible! A veces vagos estremecimientos, o enloquecidas invocaciones a Príapo, o incoherencias místicas, o recuerdos de lides, torneos y Cruzadas. También traía olores: a mieses, a humo, a fangales. El castillo los respiraba con todas sus piedras y luego los devolvía en ráfagas con algo de humedad y algo de tristeza. Otras veces el viento llegaba furioso, a latigazos, a mordiscos. Solía traer consigo impulsivos golpes de lluvia, múltiples dedos mojados, relámpagos efectistas y truenos de utilería. Todo formaba parte del orden artificialmente natural de las cosas, de la sabiduría del demiurgo, de la inocencia inventada. Pero el castillo sentía que él no se ajustaba a ese orden. No era obra de la naturaleza: ni roca viva ni peñón altivo. Pero tampoco era cosa del hombre: lugar donde se come, se duerme, se copula y se vive. Era sólo una excrecencia de otro tiempo, definitivamente ido. El castillo comprendía que su culpa consistía en no haber perdido la vida en el momento oportuno, con gracia y dignidad, permaneciendo en cambio erguido en un inútil desafío a nada o a nadie. Eso no tenía remedio. Es difícil vivir en un sueño hibernal, pero más difícil aún es morir cuando la ocasión ha pasado. Ya no podía usar de la muerte con libertad… y eso quería decir que tampoco podía usar de la vida con libertad.

Pero una noche lóbrega el viento llegó con sus múltiples voces y sus múltiples dedos, y encontró el castillo sangrando. La sangre brotaba de las junturas de las piedras, deslizándose hacia los caminos de ronda y hacia el foso. Su gusto salado tenía un enorme poder orgiástico, y al poco tiempo el viento estaba ebrio de rojos y de púrpuras. Gimió, aulló, se golpeó el pecho y se mesó los cabellos; lamió los muros hasta que desapareció el último vestigio de sangre y luego cayó, completamente dormido, en un campo de trigo.

Al día siguiente, cuando los segadores braceaban entre el mar de espigas, el viento despertó. Miró hacia el alcor, pero en la cima sólo había piedras desnudas. Y era como si el castillo no hubiera existido jamás.

“No ser ahora es como no haber sido nunca.”

Castle

Phantasmagorically breaking the quiet horizon line, the whole scenery attached to its sides, the castle oversaw with a ghostly expression the meagre houses crumpled at the foothill. From the keep, lofty on the steep rock, there could be seen the field illuminated by the elemental power of a nature, ochre and yellow as death itself. At night, the wind played among the battlements, hid in the abandoned courtyards, encircled the vertical walls with invisible hands, slid wildly along the ramps or sighed at each barbican. The castle stood still, always with its huge melodramatic gesture, its dreamy stone muteness, its haughty expression. But he liked the wind to wrap him in howling vociferations or in grim conversations among witches. Only the wind still preserved its nobility, that war-like nobility, tufted with ideas of honour and heroism, far removed from the domesticity of this century lacking Lancelots or Bradamantes. The wind was loyal and capable of inhabiting the uninhabitable, of speaking the unspeakable. The unspeakable! Sometimes vague shudders, or frenzied invocations to Priapus, or mystical incoherence, or remembrances of combats, tournaments and Crusades. He also brought smells: of cornfields, of smoke, of bogs. The castle breathed them with every stone, and then would return them in gusts, somewhat humid, somewhat sad. On other occasions, the wind came in a fury, lashing, biting. He would bring with him impulsive blows of rain, multiple wet fingers, dramatic lightning and prop thunder. Everything was part of an artificially natural order in things, of the demiurge’s wisdom, of an invented innocence. But the castle felt he did not fit in such order. A work of nature he was not: neither living rock nor lofty outcrop. Yet he was not man-made either: a place to eat, to sleep, to copulate and to live. He was but a mere excrescence from another time, definitely gone. The castle was aware that his fault was not having lost his life at the appropriate moment, with grace and dignity, and instead having stood still, uselessly defying nothing or no one. That was without cure. It is difficult to live in an idle dream, but even more difficult to die once the opportunity is past. He could no longer use death freely… which meant he could no longer use life freely either.

But on a gloomy night the wind arrived with its multiple voices and its multiple fingers, just to find the castle bleeding. Blood oozed from the rocky joins, sliding towards the allures and towards the moat. Its salty flavour had an immense orgiastic power, and shortly the wind became drunk with reds and purples. He shrieked, howled, he smote upon his breast and tore his hairs; he licked the walls until the last remnant of blood was no more and then fell, in a deep slumber, on a wheat field.

The next day, when the harvesters made strokes among the sea of spikes, the wind awoke. He looked towards the foothill, but in the summit, all there was to see were naked stones. And it was as if the castle had never existed.

“Not being now is just like never having been.”

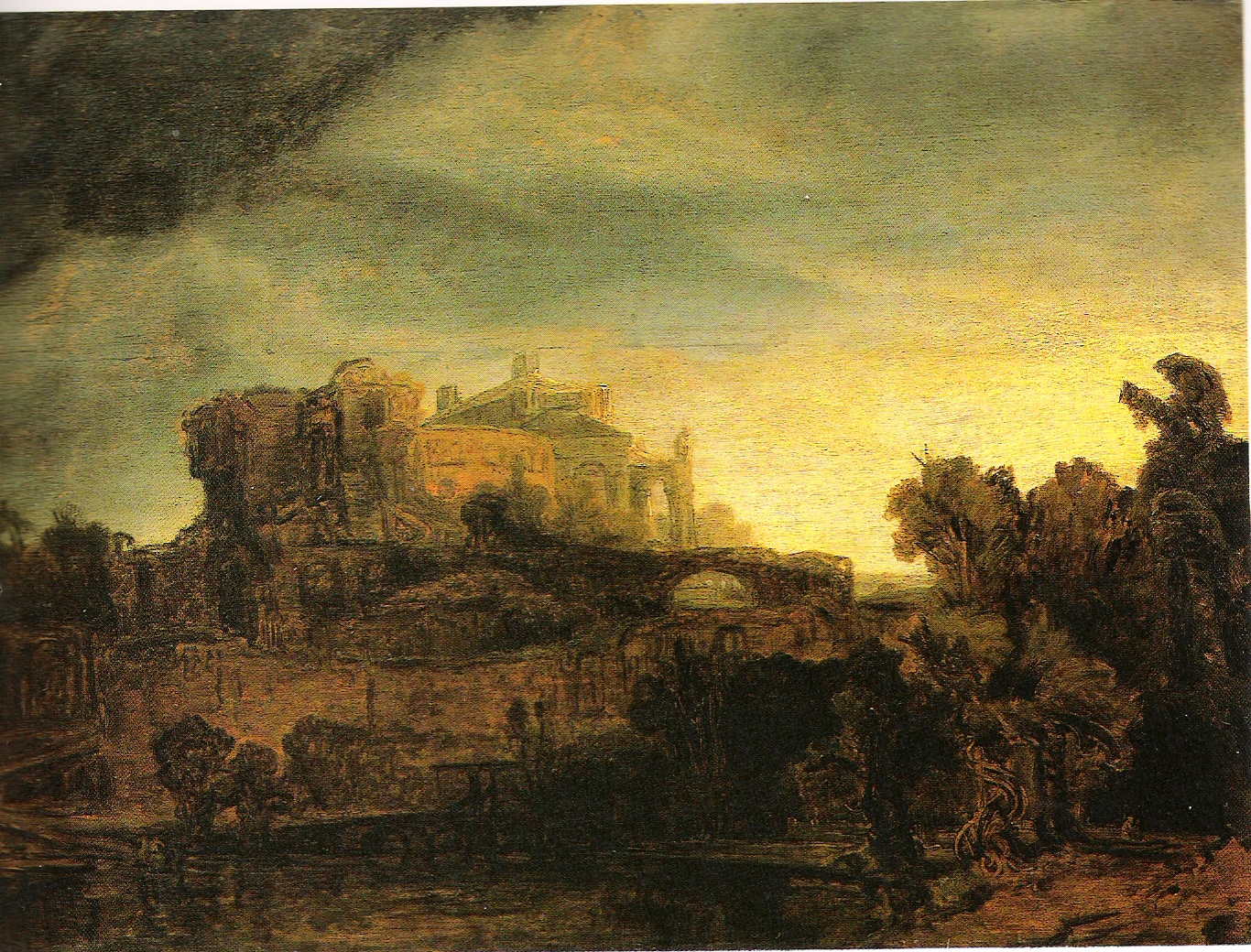

Landscape with a castle, Rembrandt

¡Titina vieja, nomás!

Sucede en todos los parques: al atardecer amanece el miedo. En las avenidas de Hampton Court, junto al lago de Palermo, entre los tilos de Wilhemshöle, en cualquier rincón del Bois. Ustedes lo saben, seguro. Más de una vez se habrán encontrado, quizás sin querer, en un parque a la hora en que los gualdas se transforman en grises y en violetas; cuando los árboles tiemblan y no de frío, cuando los cisnes se ocultan y la algarabía de los gorriones no es precisamente alegre. A pesar de la radio a transistores y del silbido que nos sale desafinado, a pesar de nada y a pesar de todo, es imposible evitar esa sensación aquí, justito aquí, en el hueco de la garganta; ese medio casi físico, o del todo físico. Y quién sabe por qué, quién sabe cómo. ¿No es cierto, Belgrave? El sol baja y el miedo sube. Ahora que caminás solo te das cuenta. Es como si te cercaran mil presencias desconocidas, mil Titinas sobrenaturales que pueden surgir del agua, del follaje o de las glorietas, con la roja pollera acampanada y la blusa blanca pero también con un halo de sombra y las cuencas de los ojos vacías.

Eso es, Belgrave: sentate de espaldas a un tronco. Si las sombras avanzan les darás la cara. No te pongás así, es sólo un poco de viento, un poco de viento que pulsa los cipreses y las casuarinas. También ¿cómo se te ocurrió citar a tu nueva conquista en este parque? Éste era el lugar de Titina. “Titina Vieja, nomás”, como solías decirle. Está bien, sí, Titina ya no existe, se ha transformado en menos que un recuerdo desde que vos dijiste basta, esto no puede seguir (buscate otro tipo percanta que yo no soy de los giles que se casan porque dejan a una mina de encargue). ¡Pobre Titina idiota! Hasta dicen por ahí que se murió porque tomó no sé qué cantidad de genioles. ¡Genioles! Los genioles no matan, y por otra parte una con cinco de clase se pega un tiro o se arroja desde un cuarto piso, lo menos. ¿Cierto, Belgrave? Pero la culpa es tuya, pelotas, por engrupir a una empleadita de tienda vulgar y silvestre. ¡Vos, Belgrave, vos que te parecés a Marcelo Mastroianni y que nunca pifiás con las mujeres! Cualquiera hubiera sido mejor que Titina, por supuesto. Acordate de la pituca aquella, la de Iturbe Nosecuántos. Y esa otra reina del girasol o algo así, tan gringuita pero tan mona. No, si cualquiera hubiera sido mejor. ¡Pero cuando vos te entusiasmas!… “¡Titina vieja, nomás!”, le decías a cada rato porque te gustaban sus ojos y ese hociquito de Bambi en decadencia. No era fea… ¡pero tan flaquita! ¡Menos carne que una bicicleta, viejo! Y para colmo el barrio y la mamá gorda y vos de novio y ravioles los domingos y ella tan honesta quiero conservarme pura pero no mi alma dame una prueba de tu amor y después las concesiones y en el momento oportuno voy a tener un chico qué hago. Vos estuviste espléndido, Belgrave, piolísimo. Hiciste bien: casarse por obligación es condenarse y condenar, jodete por sonsa, Titina, yo nunca te hablé de azahares ni de ta tan tatán, la vida hay que vivirla y yo tengo mil posibilidades, Titina vieja nomás, ya vas a ver como dentro de un mes ni te acordás de mí, yo no soy para vos, yo soy medio vago y muy bacán, olvídame por tu bien y te beso en la frente. Y resulta que a los dos días te enterás de la horrible cosa por los muchachos, jugando al billar. Y hasta ves pasar el entierro de Titina. ¡Ay, Belgrave! ¡Qué cosa fea los entierros! ¡Y qué cosa fea pensar en entierros cuando uno está en el parque, esperando a una piba más o menos linda y más o menos fácil! Vamos, parate y caminá hasta el rosedal. ¿Qué? ¿Vas a ir por la avenida principal? ¡Pero si podés acortar camino tomando ese senderito que serpentea entre las acacias, a tu derecha! ¿Tenés miedo? No, ya me parecía que no. Claro que hace un poco de frío, aquí nunca da el sol, mirá cuantos helechos y qué oscuro está todo, envuelto en una especie de neblina pegajosa. Si te levantás el cuello del saco, tal vez… ¡Pero no! ¡Si no hay ni un alma! ¿Qué es eso? ¿Por qué te detenés, Belgrave? ¿Fue el roce de una roja pollera acampanada? Otra vez Titina, Titina escondiéndose detrás de los gruesos troncos, Titina entre los helechos, Titina en la niebla, Titina mi Titina te busco por, no corrás, Belgrave, el rosedal queda para el otro lado y allí te están esperando, te están esperando, te esperarán en vano, Belgrave. En vano. Porque dentro de un minuto, justo cuando enceguecido y corriendo y buscando la seguridad de un café crucés la calle, pasará un gran camión rojo y chau Belgrave; mañana los diarios dirán un luctuoso accidente troncha joven vida etcétera. Pero a nadie se le ocurrirá agregar un pequeño detalle, un ínfimo detalle: la frase que el camionero feliz ha hecho pintar con letras blancas, entre guirnaldas y firuletes, en el frente de su vehículo. La frase que hace sonreír a veces: “Titina vieja, nomás”.

Good ol’ Titina!

It happens in every park: at sunset, fear dawns. At Hampton Court’s avenues, by the lake in Palermo, among Wilhemshöe’s lindens, at every corner of the Bois. All of you know that, for sure. More than once you must have found yourselves, perhaps unwillingly, in a park at the hour when the welds become grey and purple; when the trees shiver, not with cold, when the swans hide and the sparrows’ excitement is not precisely because of joy. In spite of the transistor radio and of our out-of-tune whistle, in spite of nothing and in spite of everything, it just cannot be helped, that feeling here, right here, in the hollow of the throat; that half-physical, or wholly physical, middle. And who knows why, who knows how. Isn’t it true, Belgrave? The sun sets and fear dawns. Now that you walk alone you realise. It’s as if you were surrounded by a thousand unknown presences, a thousand supernatural Titinas who may come out of the water, out of the foliage or the arbours, with the red flared skirt and the white blouse, but also with a shadowy halo and empty eye sockets.

That’s it Belgrave, sit with your back to a trunk. If the shadows come forward, you’ll face them. Don’t be like that, it’s just a little wind, a little wind rocking the cypresses and the ironwoods. But how could you date your new conquest in this park? This was Titina’s place. “Good ol’ Titina,” as you’d call her. Alright, yes, Titina is no more, she has become less than a memory since you said enough, this can’t go on (go look for some other guy, chick, I ain’t one of those morons marrying cause they get a bint up the duff). Poor fool, Titina! It’s even rumoured that she died after taking who knows how many pills. Pills! Pills don’t kill, and by the way, anyone with a bit of class shoots herself or jumps from a fourth floor, at least. Isn’t it true, Belgrave? But it’s your fault, you blockhead, for deceiving a mere store employee, a vulgar commoner. You, Belgrave, with your good looks like Marcelo Mastroianni’s, you’re never wrong with women! Anyone would’ve been better than Titina, for sure. Just remember that snob, that Iturbe Whatshername. Or that Sunflower queen or something, so gringo but such a cutie. Anyone would’ve been better, you know. Oh, but when you get excited!… “Good ol’ Titina!”, you’d say all the time because you fancied her eyes and that decaying Bambi-like, tiny muzzle. She wasn’t ugly… but so skinny! Come on, as thin as a rake! And on top of that the neighbourhood and the fat mom and you on a relationship and ravioli each Sunday and she so honest I wish to stay pure but no my soul give me some proof of your love and then compromises and at the right time I’ll have a baby what shall I do. You were awesome, Belgrave, you truly know how many beans make five. You did well: marrying out of obligation is sentencing and being sentenced, serves you right for being a fool, Titina, I never spoke of red roses nor this and that, life is to live it and I’ve got thousands of opportunities, good ol’ Titina, you’ll see how you won’t remember me in a month, I’m not for you, I’m sort of a slacker and quite classy, forget me for your sake and a kiss on the forehead. So it turns out that two days later, while playing billiards, the guys tell you about that horrible thing. And you even see Titina’s cortege pass by. Oh, Belgrave! Such an awful thing, burials! And such an awful thing to think about burials when one’s in the park, waiting for a somewhat cute, somewhat easy girl! Come on, get up and walk towards the Rosedal. What? You’re going through the main avenue? But you can shorten the way through that winding path among the acacias, on your right! Are you afraid? No, I thought so. Sure, it’s a bit cold, it’s always shaded in here, look how many ferns and how dark is everything, covered in some sort of sticky fog. If you turn the jacket’s collar up, perhaps… But no! Not a soul around! What’s that? Why are you stopping, Belgrave? Was it the rub of a red flared skirt? Again Titina, Titina hiding behind the thick trunks, Titina among the ferns, Titina in the mist, Titina my Titina I look for you in, don’t run, Belgrave, the Rosedal is the other way and they’re waiting for you there, they’re waiting for you, they’ll wait for you in vain, Belgrave. In vain. For in a minute, just when blinded and running and seeking security in a café you get to cross the street, a huge, red truck will pass by and bye bye, Belgrave; tomorrow the newspapers will say sorrowful accident cuts young life short etcetera. But no one shall think of adding a small detail, a tiny detail: the phrase the happy driver has had painted in white letters, surrounded by garlands and flourishes, on the front of his truck. The phrase that sometimes brings a smile: “Good ol’ Titina.”

Rosedal park in Buenos Aires

Recomendaciones a Sebastián para la compra de un espejo

Mire, Sebastián, es en la calle Juncal. Venga, acérquese; voy a decirle el número al oído —es mejor que nadie lo sepa, hay secretos que conviene guardar muy bien—. Bueno. Usted entra en la boutique y pregunta por la señora Hipólita. Le dirán que no está. Pero no se aflija, Sebastián. Sugiera que va de parte de mistress Murphy y ponga cara de inteligente. Le harán un gesto de complicidad y lo llevarán a la trastienda. Abrirán una puertecita escondida entre los brillantes vestidos que cuelgan, inmóviles pero vivos, de una increíble cantidad de perchas doradas. Podrá entonces ingresar al cuarto de los espejos. La señora Hipólita, que adora a los muchachos desgarbados como usted, le ofrecerá un cigarrillo. Acéptelo, Sebastián, acéptelo y aspírelo con delectación, porque sin duda será un cigarrillo egipcio con una pizquita de opio. Después contemple atentamente la colección de espejos, emitiendo de vez en cuando una interjección oportuna y discreta. Nada de exclamaciones altisonantes, a pesar del asombro. Y tenga en cuenta que en ningún momento hay que pronunciar la palabra “mágico”, porque se supone que usted ya sabe que todos los espejos lo son, y en especial los de la señora Hipólita.

Fíjese en ése, Sebastián. Sí, en ése, el ovalado con marco de plata. Todos los días a la siete de la tarde, refleja a la Rachel en su estupenda interpretación de “Phèdre”. Es magnífico, ¿eh? O aquel otro, tan profundo en el misterio de su azogue, tan rico en las volutas rococó que lo rodean. No niego que es maravilloso. Pero no se lo aconsejo, porque al sonar las doce campanadas de la medianoche muestra a un oficial de húsares de Grodno asesinado por su novia vampiro. ¡Brrr! Mejor es el que está a su derecha; menos morboso y sumamente eficiente. Hasta educativo: Imagínese: a las seis de la mañana deja ver a las damas mendocinas bordando una bandera. Es un espejo quizás demasiado madrugador, claro, pero tan patriótico como un discurso de fiesta cívica. En fin… hay que reconocer que la señora Hipólita tiene una colección fabulosa. Espejos teatrales, pasionales, históricos… También tiene los que reflejan el futuro, pero sólo los muestra previa presentación del certificado de buena salud, porque una vez tuvo problemas con el profesor N. El pobre era cardíaco y… bueno, usted sabe el resto, salió en todos los diarios.

Lo importante es que usted, Sebastián, puede comprar el espejo que más le interese. Los precios son exorbitantes, es cierto, pero no cualquiera puede darse el lujo de poseer cosas así. Además, si sonríe usted como está sonriendo justamente ahora, no dudo que la señora Hipólita le hará una rebaja o le dará facilidades. Es una mujer muy tierna, muy sensible, muy maternal a veces. Aunque tan arrugada que… pero eso no viene al caso. Elija el espejo que prefiera. Deje su dirección, y mañana mismo lo enviarán a su casa. ¿Un consejo? No lo coloque en el living ni en el escritorio ni en ningún lugar por donde pase mucha gente. Sobre todo porque sus amigos son muy convencionales, muy burgueses, y el espejo puede reflejar algo irritante, impropio para la gente decente. Suponga que se le ocurra comprar el espejo de Paolo y Francesca… ¿Qué diría su abuelita materna, Sebastián, que va a misa todos los domingos? No, hay que tener cuidado, hay que ser respetuoso de las convicciones y de la moral dé los demás. Yo le sugeriría (y perdóneme el atrevimiento), que ponga al espejo en el altillo, con otros trastos viejos. Más todavía que lo cubra con algún paño opaco. Y otra cosa aún, la más importante de todas: con los espejos de la señora Hipólita es imprescindible ser puntual. Puntualísimo. Si no llega usted á la hora exacta, no verá el espectáculo. Ni Rachel declamando, ni húsar sangrando, ni damas mendocinas bordando, ni Paolo y Francesca fornicando (perdón otra vez, hay palabras que realmente no suenan muy bien). Si llega tarde sólo verá su propia cara, la misma de siempre, Sebastián, tan angulosa, tan mística. Pero eso es lo de menos. Lo grave sucede cuando la curiosidad lo impulsa a apresurarse y lo obliga a llegar demasiado temprano, para averiguar cómo prepara el espejo su “mise en scène”. Eso puede ser fatal, porque los espejos no toleran la curiosidad. Y sucederá que, al arrancar el paño que lo cubre y enfrentarlo, se encontrará usted con que está vacío, con que no refleja nada, con que su imagen en el espejo no existe y por lo tanto, claro, usted tampoco. Es una platónica verdad. Al no verse en el espejo, sin duda se llevará usted las manos a la cabeza, en un gestó de terror y de asombro. Pero como usted no existe, descubrirá que no tiene manos ni cabeza. Intentará salir corriendo pero tampoco tendrá piernas. Y se quedará por siempre allí, atrapado en el espejo vacío que alguna vez retomará a la colección de la eterna señora Hipólita y reflejará, para otro cliente como usted, joven y desgarbado, la imagen ascética de Sebastián, oh Sebastián pálido de terror, sólo durante un minuto y a la hora en que se pone el sol.

Advice for Sebastián to buy a mirror

Look, Sebastián, it’s on Juncal street. Come, come close; I’ll whisper the number in your ear —no one else should know, it’s best to keep well certain secrets—. Alright. You go into the boutique and ask for Mrs. Hipólita. They’ll say she is not there. But don’t worry, Sebastián. Suggest you go on behalf of Mademoiselle Fleury and try to look smart. They’ll make a gesture of complicity and take you into the back room. They shall open a small door hidden among the scintillating dresses hanging, immobile yet alive, from an amazing number of golden hangers. Then, you may enter the room of mirrors. Mrs. Hipólita, who is so fond of ungainly boys like you, will offer you a cigarette. Accept it, Sebastián, accept it and puff with delight, for it will surely be an Egyptian cigarette with a tiny pinch of opium. Afterwards, regard the collection of mirrors with care, saying an appropriate and discreet interjection occasionally. No high-flown comments, in spite of the awe. And bear in mind not to mention the word “magical” at any time, since you’re meant to know already that all mirrors are, particularly Mrs. Hipolita’s.

Take a look at this one, Sebastián. Yes, that one, the oval with a silver frame. Every day at seven in the afternoon, it reflects Mlle. Rachel in her outstanding performance of “Phèdre”. Magnificent, eh? Or that one, so profound in the mystery of its coating, so rich in the rococo volutes around it. I won’t deny it’s wonderful. But I wouldn’t recommend it, for at the sound of the twelve strokes of midnight, it shows an officer of the Grodno hussars being murdered by his vampire girlfriend. Brrr! Better still is the one on your right; less gruesome and most efficient. Educational, even; just imagine: at six in the morning, you may see the Mendocenean ladies embroidering a flag. Perhaps it might be quite an early-rising mirror, of course, but as patriotic as a speech on a public holiday. Well… We must admit that Mrs. Hipólita has an outstanding collection. Theatrical, passionate, historical mirrors… She also has some which reflect the future, but these are shown only upon presenting a certificate of good health, because she had a problem once with Professor N. The poor soul was a heart patient and… Well, you know the rest, it appeared in all the newspapers.

What’s important is that you, Sebastián, can buy the mirror you like the most. The prices are astronomical, that’s true, but not everyone can afford to have something like this. Also, if you smile just like you’re smiling right now, I’m sure Mrs. Hipólita will offer you a discount or payment facilities. She’s a very tender woman, very sensitive, very motherly sometimes. But she’s so wrinkled that… Anyway, that’s not relevant now. Choose the mirror you like. Give them your address and they’ll send it home to you tomorrow. A piece of advice? Do not place it in the living room, in the study, nor in any place where too many people pass by. Above all because your friends are too conventional, too bourgeois, and the mirror may reflect something unpleasant, improper for respectable people. Imagine you wished to buy Paolo and Francesca’s mirror… What would your maternal grandma say, Sebastián, she who goes to church every Sunday? No, you must be careful, you must be respectful of other people’s principles and morals. I would suggest —and forgive my nerve— placing the mirror in the attic, together with other junk. Furthermore, I would cover it with some drab cloth. Yet another thing, the most important one: with Mrs. Hipólita’s mirrors it is mandatory to be punctual. Strictly punctual. If you don’t arrive at the exact time, you won’t see the show. No Mlle. Rachel reciting, no bleeding hussar, no Mendocenean ladies embroidering, no Paolo and Francesca fornicating (I apologise once again, some words just don’t sound well). If you’re late you’ll just see your own face, the same as always, Sebastián, so edgy, so mystical. But that’s the least of it. The serious thing occurs when curiosity impels you to hasten and makes you arrive too early, to find out how the mirror prepares its “mise en scène”. This can prove to be fatal, because mirrors do not tolerate curiosity. And it will happen that when you take off the cloth that covers it and face it, you shall find that it is empty, that it doesn’t reflect anything, that your own image in the mirror doesn’t exist and so, of course, neither do you. It’s a Platonic truth. When you don’t see yourself in the mirror, you’ll surely put your hands on your head, in a gesture of horror and amazement. But since you do not exist, you shall find you have no hands nor head. You’ll try to run away, but you won’t have legs either. And you’ll stay there forever, trapped inside the empty mirror that at some time shall return to the eternal Mrs. Hipólita’s collection and will reflect, for another client like you, young and ungainly, the ascetic image of Sebastián, oh Sebastián, pale with horror, just for a minute and at the time when the sun sets.

Leave A Comment