John Donne

Obsequies to Lord Harington (1614)

John Donne

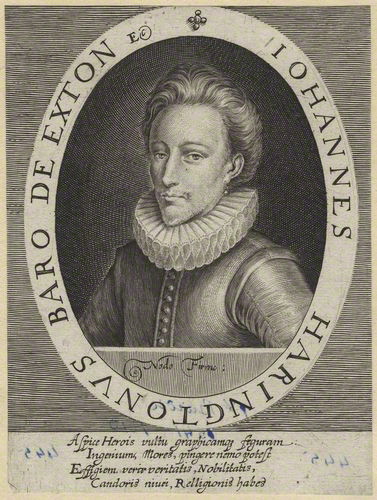

The great English poet John Donne (1571/1572-1631) composed this poem in 1614, after the death of John Harington, 2nd Baron Harington of Exton (1592–1614). This elegy, in typical Donne fashion, appeals profusely to metaphors and conceits based on philosophical, theological, scientific, historical, and mythological concepts. The poem is not only a lament, but also an extended meditation on worldly and religious matters.

Set in a classic form of English poetry, it comprises 258 verses in iambic pentameter rhyming couplets. In my poetic version, I sought to preserve, first and foremost, the depth and density of images and conceits in Donne’s poem, sticking to its discursive character. Then, I tried to imitate, though from a distance, the metric regularity and sonority of its verses. Thus, I chose the Spanish alexandrine, whose larger quantity of syllables gave room to preserve the semantic charge as far as possible (as appropriate for a decidedly philosophical poem). Besides, I chose an assonant rhyme for each couplet, which, though not as ‘perfect’ as the original’s consonant rhymes, lent flexibility to follow the discourse more closely, not foregoing, however, the binding sound effects of the rhymes.

I submitted this translation to the 2025 Premio de Traducción Paula de Roma of Universidad Nacional de Córdoba in Argentina, under the category “Unpublished poetry translation”. It was subsequently shortlisted by an immensely prestigious jury, along with other works by colleagues I personally admire. Let me thank the organisers and jury of said competition. Furthermore, “Obsequies to Lord Harington” is one of four funerary poems by John Donne which I translated and will be edited next year.

Exequias a Lord Harington

| FAIR soul, which wast not only, as all souls be, Then when thou wast infusèd, harmony, But didst continue so; and now dost bear A part in God’s great organ, this whole sphere: If looking up to God, or down to us, Thou find that any way is pervious ’Twixt Heav’n and Earth, and that men’s actions do Come to your knowledge, and affections too, See, and with joy, me to that good degree Of goodness grown, that I can study thee, And, by those meditatïons refined, Can unapparel and enlarge my mind, And so can make by this soft ecstasy, This place a map of Heav’n, myself of thee. Thou seest me here at midnight: now all rest; Time’s dead-low water; when all minds divest Tomorrow’s business, when the labourers have Such rest in bed, that their last churchyard grave, Subject to change, will scarce be a type of this; Now when the client, whose last hearing is Tomorrow, sleeps; when the condemnèd man (Who when he opens his eyes, must shut them then Again by death), although sad watch he keep, Doth practise dying by a little sleep— Thou, at this midnight, seest me, and as soon As that sun rises to me, midnight’s noon, All the world grows transparent, and I see Through all, both church and state, in seeing thee. And I discern by favour of this light Myself, the hardest object of the sight. God is the glass; as thou, when thou dost see Him who sees all, seest all concerning thee, So, yet unglorified, I comprehend All, in these mirrors of thy ways and end. Though God be truly our glass through which we see All, since the being of all things is he, Yet are the trunks which do to us derive Things in proportion fit by pèrspective Deeds of good men: for by their living here Virtues indeed remote seem to be near. But where can I affirm, or where arrest My thoughts on his deeds? which shall I call best? For fluid virtue cannot be looked on, Nor can endure a contemplatïon; As bodies change, and as I do not wear Those spirits, humours, blood I did last year, And, as if on a stream I fix mine eye, That drop on which I looked is presently Pushed with more waters from my sight, and gone, So in this sea of virtues, can no one Be insisted on: virtues, as rivers, pass, Yet still remains that virtuous man there was; And as if man feed on man’s flesh, and so Part of his body to another owe, Yet at the last two perfect bodies rise, Because God knows where every atom lies; So, if one knowledge were made of all those Who knew his minutes well, he might dispose His virtues into names, and ranks, but I Should injure nature, virtue and destiny, Should I divide and discontinue so Virtue which did in one entireness grow. For as he that would say ‘Spirits are framed Of all the purest parts that can be named’ Honours not spirits half so much as he Which says ‘They have no parts, but simple be’, So is’t of virtue; for a point and one Are much entirer than a million. And had Fate meant to have his virtues told, It would have let him live to have been old, So then that virtue in season and then this We might have seen, and said that now he is Witty, now wise, now temperate, now just: In good short lives, virtues are fain to thrust, And to be sure betimes to get a place, When they would exercise, lack time and space. So was it in this person, forced to be For lack of time, his own epitome, So to exhibit in few years as much As all the long-breathed chronicles can touch. As when an angel down from Heav’n doth fly, Our quick thought cannot keep him company: We cannot think ‘Now he is at the Sun, Now through the Moon, now he through th’air doth run’, Yet when he’s come, we know he did repair To all ’twixt Heav’n and Earth, Sun, Moon, and air, And as this angel in an instant knows, And yet we know, this sudden knowledge grows By quick amassing several forms of things, Which he successively to order brings; When they, whose slow-paced, lame thoughts cannot go So fast as he, think that he doth not so; Just as a perfect reader doth not dwell, On every syllable, nor stay to spell, Yet without doubt, he doth distinctly see, And lay together every A and B; So in short-lived good men’s not understood Each several virtue but the compound good. For they all virtues’ paths in that pace tread As angels go and know, and as men read. O why should then these men, these lumps of balm Sent hither this world’s tempests to becalm, Before by deeds they are diffused and spread, And so make us alive, themselves be dead? O soul, O circle, why so quickly be Thy ends, thy birth and death closed up in thee? Since one foot of thy compass still was placed In Heav’n, the other might securely’ve paced In the most large extent through every path Which the whole world or man, th’abridgement, hath. Thou knewst that though the tropic circles have (Yea, and those small ones which the poles engrave) All the same roundness, evenness, and all The endlessness of th’equinoctial, Yet when we come to measure distances, How here, how there the Sun affected is, Where he doth faintly work, and where prevail, Only great circles then can be our scale: So, though thy circle to thyself express All, tending to thine endless happiness, And we by our good use of that may try Both how to live well young and how to die, Yet, since we must be old, and age endures His torrid zone at Court, and calentures Of hot ambitions, irreligion’s ice, Zeal’s agues, and hydroptic avarice (Infirmities which need the scale of truth As well as lust and ignorance of youth), Why didst thou not for those give medicines too And by thy doing tell us what to do? Though, as small pocket-clocks, whose every wheel Doth each mismotion and distemper feel, Whose hand gets shaking palsies, and whose string (His sinews) slackens, and whose soul, the spring, Expires or languishes, whose pulse, the fly, Either beats not, or beats unevenly, Whose voice, the bell, doth rattle or grow dumb Or idle, as men which to their last hours come, If these clocks be not wound, or be wound still, Or be not set, or set at every will, So youth be easiest to destructïon If then we follow all, or follow none; Yet, as in great clocks which in steeples chime, Placed to inform whole towns to employ their time, An error doth more harm, being general, When small clocks’ faults only on th’wearer fall, So work the faults of age, on which the eye Of children, servants, or the state rely. Why wouldst not thou then, which hadst such a soul, A clock so true, as might the Sun control, And daily hadst from him who gave it thee Instructions such as it could never be Disordered, stay here as a general And great sundial, to have set us all? Oh why wouldst thou be any instrument To this unnatural course, or why consent To this not miracle but prodigy: That where the ebbs longer than flowings be, Virtue, whose flood did with thy youth begin, Should so much faster ebb out than flow in? Though her flood were blown in by thy first breath, All is at once sunk in the whirlpool death, Which word I would not name, but that I see Death, else a desert, grown a court by thee. Now I am sure, that if a man would have Good company, his entry is a grave. Methinks all cities, now, but anthills be, Where, when the sev’ral labourers I see For children, house, provision, taking pain, They’re all but ants, carrying eggs, straw, and grain; And churchyards are our cities, unto which The most repair that are in goodness rich. There is the best concourse and confluence, There are the holy suburbs, and from thence Begins God’s city, New Jerusalem, Which doth extend her utmost gates to them; At that gate then, triumphant soul, dost thou Begin thy triumph. But, since laws allow That at the triumph day the people may All that they will ’gainst the triumpher say, Let me here use that freedom, and express My grief, though not to make thy triumph less. By law, to triumph none admitted be Till they as magistrates get victory: Though then to thy force, all youth’s foes did yield, Yet till fit time had brought thee to that field To which thy rank in this state destined thee, That there thy counsels might get victory And so in that capacity remove All jealousies ’twixt prince and subjects’ love, Thou couldst no title to this triumph have. Thou didst intrude on death, usurped’st a grave. Then (though victoriously) thou’dst fought as yet But with thine own affections, with the heat Of youth’s desires, and colds of ignorance; But till thou shouldst successfully advance Thine arms ’gainst foreign enemies, which are Both envy and acclamations popular (For both these engines equally defeat, Though by a divers mine, those which are great), Till then thy war was but a civil war, For which to triumph none admitted are; No more are they who, though with good success, In a defensive war their power express. Before men triumph, the dominïon Must be enlarged, and not preserved alone. Why shouldst thou, then, whose battles were to win Thyself from those straits Nature put thee in, And to deliver up to God that state Of which he gave thee the vicariate (Which is thy soul and body) as entire As he, who takes endeavours, doth require, But didst not stay to1enlarge his kingdom too, By making others what thou didst to do; Why shouldst thou triumph now, when Heav’n no more Hath got, by getting thee, than’t had before? For Heav’n and thou, ev’n when thou livedst here, Of one another in possession were; But this from triumph most disables thee: That that place which is conquerèd must be Left safe from present war and likely doubt Of imminent commotions to break out. And hath he left us so? or can it be His territory was no more but he? No, we were all his charge: the diocese Of ev’ry exemplar man the whole world is, And he was joinèd in commissïon With tutelar angels, sent to everyone. But though this freedom to upbraid and chide Him who triumphed were lawful, it was tied With this: that it might never reference have Unto the Senate, who this triumph gave; Men might at Pompey jest, but they might not At that authority by which he got Leave to triumph before by age he might; So though, triumphant soul, I dare to write, Moved with a reverential anger, thus, That thou so early wouldst abandon us, Yet am I far from daring to dispute With that great sovereignty whose absolute Prerogative hath thus dispensed for thee ’Gainst nature’s laws, which just impugners be Of early triumphs; And I (though with pain) Lessen our loss to magnify thy gain Of triumph, when I say it was more fit That all men should lack thee than thou lack it. Though then in our time be not sufferèd That testimony of love unto the dead, To die with them, and in their graves be hid, As Saxon wives, and French soldurii did; And though in no degree I can express, Grief in great Alexander’s great excess, Who at his friend’s death made whole towns divest Their walls and bulwarks which became them best: Do not, fair soul, this sacrifice refuse, That in thy grave I do inter my Muse, Who, by my grief, great as thy worth, being cast Behindhand, yet hath spoke, and spoke her last. |

Bella alma, que no solo fuiste al ser infundida, cual toda alma es entonces, armonía, sino que lo seguiste siendo; y ahora albergas parte de aquel gran órgano de Dios, toda esta esfera: si a Dios alzas la vista o hacia nosotros cae y descubres alguna vía que sea permeable entre el Cielo y la Tierra, y llega a tu intelecto cada acto de los hombres y también cada afecto, cura, y con alegría, de que el buen grado alcance de bondad para yo poder así estudiarte, y meditando en esto, que quede yo acendrado para desataviar mi mente y darle espacio, y que este suave éxtasis me lleve a convertir este lugar en mapa del Cielo y yo de ti. Me ves a medianoche: todo aquí ya reposa, la bajamar del tiempo; las mentes se despojan del quehacer de mañana; en la cama el obrero goza de tal descanso, que el final tras su entierro, sujeto a cambio, apenas será un émulo de este; cuando, antes de su última audiencia, el cliente duerme hasta la mañana; cuando el ya condenado, quien al abrir los ojos pronto habrá de cerrarlos otra vez en la muerte, aunque triste desvelo guarde, ensaya el morir con un poco de sueño; tú, en esta medianoche, me ves, y así como ese sol, de esta medianoche mediodía, aparece para mí, transparenta el mundo entero, y miro Iglesia, Estado y todo en viéndote a ti mismo. Y por favor de aquella luz a mí me discierno, yo que soy a la vista tan difícil objeto. Dios es el vidrio; así como tú, al ver a Aquel que lo ve todo, todo lo que te atañe ves, así yo, todavía sin gloria, lo comprendo todo sobre tus sendas y fin en ese espejo. Aunque en verdad sea Dios nuestro vidrio que toda vista exhibe, pues es el ser de cada cosa, aun así, son las trompas que las cosas nos muestran, obra de perspectiva, en la proporción nuestra, los hechos de los buenos hombres: pues aquí moran, y así parecen cerca las virtudes remotas. Pero ¿dónde afirmar o apuntar mis ideas sobre sus actos? ¿Cuál diré que más supera? Pues la virtud fluida no se abre a la visión, no puede soportar una contemplación; como cambian los cuerpos, y como yo no traigo los humores, espíritus, sangre de años pasados; y así como en un río yo fijo el ojo y esa gota a la que observo ya al momento la empellan más aguas que la apartan de mi vista y se pierde, así en ninguna de este mar de virtudes puede insistirse: cual ríos, las virtudes circulan, pero el hombre virtuoso que fue aún perdura; y cual si un hombre come la carne de otro hombre y parte de su cuerpo al otro corresponde, pero al fin se levantan dos cuerpos acabados porque Dios sabe dónde se encuentra cada átomo; así, de hacerse un solo saber con el de todos los que bien conocieron sus minutos, él solo dispondría sus virtudes por nombre y jerarquía; pero a virtud, destino, natura insultaría si yo así dividiera y discontinua hiciera a la virtud que en una integridad creciera. Pues tal como el que afirma que el espíritu enmárcase entre todas las partes más puras designables ni de cerca los honra tanto como el que dice que ellos no tienen partes, sino más bien son simples, tal es con la virtud, puesto que un solo punto y uno son más enteros que un millón y por mucho. Y de haber el Destino deseado que contaran sus virtudes, le hubiera dado el que alcanzara la vejez, y así aquella virtud en madurez y luego esto hubiéramos visto y dicho que él es ya ingenioso, ya sabio, ya templado, ya ecuánime: las buenas vidas breves tienden a abarrotarse de virtudes, y pronto su buen lugar obtienen, si bien de espacio y tiempo para ejercer carecen. Fue así en esta persona, forzada a ser su propio epítome por falta de tiempo y, en muy pocos años, a mostrar tanto como todas las crónicas del más largo aliento expresan en sus nóminas. Como, al bajar volando un ángel desde el Cielo, no nos es suficiente el vivaz intelecto para seguirle el rastro, no podemos pensarlo: “Ya por el Sol, la Luna, ya en el aire va raudo”; pero cuando aquel llega, sabemos que pasó por todo el Cielo y Tierra, la Luna, el aire, el Sol, y así como este ángel conoce en un momento, y aun así sabemos que ese conocimiento repentino se hace agrupando diversas formas de cosas rápido, a las que él ordena en sucesión, y aquellos cuyo lento y pobre pensar no es tan veloz creen que no así él compone; así como un lector perfecto no se queda en las sílabas solas, ni todo deletrea, pero sin duda alguna distintamente ve y logra componer cada A y cada B; así en quien poco vive no se aprehende, si es bueno, cada virtud distinta, sino el bien cual compuesto. Pues por toda virtud van al ritmo que entienden y se mueven los ángeles y al que los hombres leen. ¡Ay! ¿Y por qué estos hombres, estas masas de bálsamo, a aplacar la tormenta del mundo aquí enviados, antes de difundirse y esparcirse en hazañas, para así darnos vida, ya están muertos? ¡Ay, alma, ay, círculo! ¿Por qué quedan así de rápido tus fines, nacimiento y muerte, en ti cerrados? Ya que fija tenía tu compás una pata en el Cielo, hubiera ido la otra confiada por la extensión más grande de todos los senderos que tiene el mundo entero o el hombre, su compendio. Sabes que, aunque los círculos de los trópicos tengan (y también los pequeños que los polos encierran) la misma redondez, uniformidad, todos la misma infinitud que aquel del equinoccio, aun así, si medimos distancias, cómo aquí se ve afectado el Sol o cómo incide allí, dónde obra débilmente, dónde se impone y gana, solo los grandes círculos pueden ser nuestra escala: siendo así, aunque tu círculo te exprese todo a ti, y te oriente a tu propia felicidad sin fin, y nosotros, usándolo bien, podamos probar el vivir bien de jóvenes y, aún así, expirar; como hemos de ser viejos, como la edad endura en la Corte su zona tórrida y calenturas de ardientes ambiciones, la irreligión cual hielo, la hidrópica avaricia y las fiebres del celo (enfermedades que urgen la verdad y su escala así como la joven lujuria e ignorancia), ¿por qué tú no nos diste también a ello remedio ni indicaste qué hacer a través de tus hechos? Aunque, como un reloj de bolsillo, que siente en cada rueda el mal movimiento y destemple; cuya cuerda se afloja cual si fueran tendones y tiembla en las manillas; cuya alma, el resorte, expira o languidece; cuyo pulso, el volante, bate sin proporción o ni siquiera bate; cuya voz, la campana, es muda o carraspea, o delira, cual hombre que a su última hora llega; y como estos relojes, si están faltos o ahítos de cuerda o no se ajustan o lo hacen a capricho, así la juventud se hace más vulnerable a la ruina si sigue ya a todos, ya a nadie. Pero, así como un gran reloj, que en una aguja repica y marca a pueblos enteros cómo se usa el tiempo, hace más daño general con su error, mas el fallo del chico solo va al portador; así obran los errores de la edad, donde fijan los niños, los sirvientes y el estado la vista. ¿Por qué, entonces, tú, que tal alma tenías, reloj que, de tan cierto, al Sol regir podría, que Aquel que te la dio a diario te enviaba instrucciones, guardando que nunca te tocara el desorden, no aquí quedaste como gran reloj solar que a todos nos pudiera ajustar? Ay, ¿por qué fuiste tú instrumento de este curso antinatural, por qué consentir a ese no milagro, más bien prodigio: que el reflujo siendo más duradero siempre que el propio flujo, la virtud, que ya en ti siendo joven fluyó, menguara tan más pronto que por cuanto creció? Aunque en tu primer hálito su flujo inspirares, todo se hunde a la vez en la mortal vorágine, palabra que no habría de nombrar, pero crece rodeándote cual corte un desierto: la muerte. Ahora estoy seguro de que si un hombre gusta de buena compañía su entrada es una tumba. Se me hace, ya, que toda urbe es un hormiguero, en la que los muchísimos obreros que yo observo, poniendo tanto esfuerzo por hijos, casa, abasto, son hormigas que cargan huevos, briznas y granos; y son los cementerios como nuestras ciudades, donde más se repara el que es rico en bondades. Allí están la mejor confluencia y concurso, y allí nomás empieza, tras los santos suburbios, la ciudad de Dïos, la Jerusalén Nueva, que hasta ellos extiende sus puertas más externas. Ante esa puerta, alma triunfante, das principio, entonces, a tu triunfo. Pero, en tanto que es lícito que en el día del triunfo el pueblo sin tapujos exprese lo que quiera contra aquel que lo obtuvo, aquí, sin desdeñar el tuyo, he de expresar mi dolor apelando a aquella libertad. Según la ley, el triunfo podía ser otorgado solo a quienes vencieran siendo ellos magistrados: aunque todo enemigo juvenil a tu fuerza cediera, hasta que el tiempo justo te conscribiera al campo que tu estado y rango deparaban, tal que allí la victoria tus consejos ganaran, y que en tal dignidad, respecto del amor entre príncipe y súbditos, quitaras el rencor, no tenías ningún derecho a este triunfo. Tú usurpaste una tumba, tú, de la muerte intruso. Hasta entonces, si bien victorioso, tan solo habías combatido con tus afectos propios: el calor del deseo juvenil, la ignorancia gélida; pero hasta oponer con prestancia tus armas a enemigos extranjeros, que son la envidia popular y toda aclamación (pues ambas maquinarias derrotan por igual, socavando por vías varias al principal), tu guerra era tan solo una guerra civil, por la que a nadie un triunfo se le puede admitir; tampoco pueden más quienes, aunque exitosos, en guerra defensiva se muestran poderosos. Antes de dar un triunfo a un hombre, han de ensancharse los dominios y no apenas preservarse. Y entonces, ¿por qué a ti, que libraste tus luchas por salir del estrecho en donde la Natura te había cerrado y dar de vuelta aquel estado, del que Dios te entregara antes el vicariato (que son tu alma y tu cuerpo), ordenado y entero, tal como exige aquel que acepta los esfuerzos, pero no te quedaste a ensanchar más las lindes del Reino, instando a otros a hacer lo que tú hiciste; por qué otorgarte un triunfo ahora, si no tiene el Cielo más que antes por el solo tenerte? Porque cuando aún aquí vivías, tú y el Cielo se poseían mutuamente. Esta es, empero, la principal razón del triunfo a ti vedado: que ha de permanecer el lugar conquistado libre de actuales guerras y sin ningún temor a que súbitamente surja una conmoción. ¿Y él nos dejó así? ¿Pudo su territorio haber sido no más que sí mismo? No, todos estábamos a cargo de él; quien sirve de ejemplo recibe como diócesis para sí el mundo entero, y a él unidos iban en comisión los ángeles enviados a cada cual como tutelares. Y aunque fuera legítima aquella libertad de advertir e increpar al que entrara triunfal, debía atarse a esto: que nunca refiriera a aquel mismo Senado que el triunfo concediera; bien podían los hombres de Pompeyo burlarse, pero nunca de aquella autoridad que antes del tiempo estipulado le dio permiso al triunfo; así, alma triunfante, si bien yo me aventuro a escribir de esta forma, movido de un enojo reverencial, sintiendo tan pronto tu abandono, lejos de mí el querer a esa soberanía inmensa discutirle, cuya prerrogativa absoluta te dio a ti esta dispensa en contra de las leyes de la naturaleza, justas impugnadoras de los triunfos tempranos; y yo (aunque con dolor) nuestra resta rebajo para magnificar tu triunfo cuando digo: que los hombres no puedan tenerte es más digno que el que tú no lo tengas. Y aunque no admitan nuestros tiempos el testimonio de amor hacia los muertos que era morir con ellos y ocultarse en sus fosas, cual soldurii franceses, cual esposas sajonas; y aunque de ningún modo pueda expresar angustia como el gran Alejandro hizo en gran desmesura, quien, al morir su amigo, despojó de bastiones y muros bien ornantes a varias poblaciones; bella alma, no de este sacrificio rehúyas: que yo entierre también en tu tumba a mi Musa, que tarde echada a causa de mi pena, al valor tuyo igual, aun así, por vez última habló. |

Leave A Comment