Alberto Laiseca

Tres cuentos de

Matando enanos a garrotazos (1982)

Vínculo al texto original:

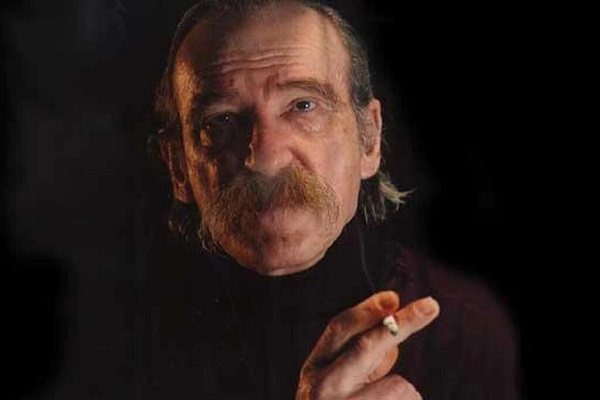

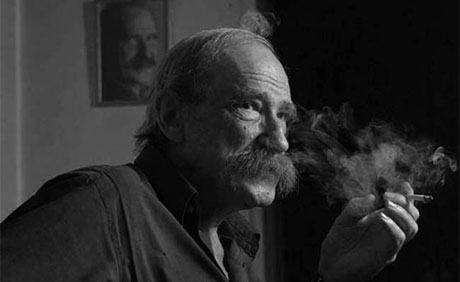

Alberto Laiseca

Es difícil entender un caso como el de Alberto Laiseca. Se trata de un autor cuya obra es tan vasta e imaginativa, un creador de mundos con una cultura de dimensión enciclopédica, un narrador cautivante, un artista que expresa con gracia tanto el terror como la belleza. Se trata nada menos que del padre de ese monstruo que es Los sorias, la novela más extensa de la literatura argentina y un libro que, para muchos, debe ubicarse a la altura de las más grandes obras de la literatura universal. Pero, cosa curiosa —y sumamente injusta—, no cuenta Alberto Laiseca con un público lector y una notoriedad que se corresponda, siquiera un poco, con la magnitud de su genio. (Sí debe decirse que quienes lo leen, lo admiran; y quienes lo admiran, lo hacen fervientemente). Una clara muestra de la incongruencia entre el peso específico de la obra de Laiseca y el lugar que ocupa es la escasa cantidad de libros suyos que han sido traducidos. Sirva como ejemplo la monumental Los sorias, su indiscutida obra maestra: ¡no ha sido traducida a ningún idioma!

No pretendo explayarme aquí sobre este tema, pero es imprescindible mencionarlo para entender por qué me atrevería a decir que traducir a este autor es un acto de justicia. Estos tres cuentos de su primer libro de cuentos cortos, Matando enanos a garrotazos, guardan estrecha relación con el mundo de Los sorias. De hecho, estos cuentos se publicaron en 1982, el mismo año en el que Laiseca terminó de escribir su novela, publicada 15 años más tarde. Mi intención al traducirlos al inglés es aportar al menos una pequeñísima ventana a esa mente genial que creó un realismo delirante. Ojalá que estos tres cuentos sean un paso hacia el descubrimiento de Alberto Laiseca en el mundo angloparlante y un pequeño acto de justicia para un genio poco reconocido (por ahora).

Por último, me gustaría aclarar que, antes de publicar estas traducciones, intenté ponerme en contacto con Julieta Laiseca, hija del escritor y titular de los derechos de su obra. Lamentablemente, no encontré todavía la manera de comunicarme con ella y por eso hago saber que, de existir algún problema de derechos por haber publicado estas traducciones, de inmediato haré lo que sea necesario para solucionarlo. Estaría encantado de poder comunicarme con Julieta para compartir con ella este breve trabajo y, en caso de que llegue a leerme, puede contactarme a través de mi correo electrónico.

Matando enanos a garrotazos

Tramp Beach Resort

Their learned Raggednesses, misters Moyaresmio and Crk Iseka, were resting that morning on the beach sand at Gazophylacium Bay; this place was located on the western Technocracy, by the Thracian Ocean, much further south the parallel that passed through Monitoria, the country’s capital.

This bay was virtually the last Garden before the great western desert, close to the Caliphal border, known as Satan’s Bronze.

As no one went to said paradise beach, for the tycoons had not discovered it in time, little by little it became a great tourist attraction for tramps. Bums and beggars from all over the Technocracy spent their holidays there, pitching sackcloth tents.

When the magnates and hierarchs realised what a place they had lost, it was too late. Who would dare —and by what means— to expel the poor little wretches, who numbered the hundreds and were protected by no less than the dreaded Benefactor himself (so was also called the Monitor or Head of State), with whom they had found grace?

Meanwhile the tramps, most chuffed with the situation, travelled all over the enormous country, doing whatever they pleased all year round and spending one or two summer months in Gazophylacium Bay.

They arrived at the beach attired in their costliest plumages, and sparkling with filth.

Misters Moyaresmio and Crk were comfortably settled under a parasol as faded as if drawn from the sea bottom. They wore shorts made out of curtain scraps, with stitched flowers cut from fashion magazines, and cardboard havaianas tied with twines.

The morning was very beautiful and not too hot; the water, a few metres from them, was clear and pure.

Said Mr. Moyaresmio, as he took a long sip of frozen white wine:

“There is nothing like natural life.”

While they drank, and thanks to an antediluvian phonograph with a tiny winding handle, adapted to 33 rpm and automatic sequencing, these two Enlightened despots of poverty listened to: Tales of Bavaria, The Beer March, Wenn der Toni mit der Vroni, Stachus Polka with Rudi Knabl on zither, Luisa the Shooter, and There’s a Beer Hall in Munich, with Otto Ebner and his wind orchestra[1].

Close to them there was a short train of stands selling sausages and hot-dogs, built with wood imported from Hindu huts, which grow like plants along the shore of the Ganges and came with worms and all; so rotten the planks that you could sink in a finger.

Around the beach ran numerous rickshaws for wealthy tramps, who paid the pullers with sugar and matches.

Naturally, there were lifeguards wearing football shirts full of holes, with two pin-held paper signs in their front and back:

LIFEGUARD

The lifeguards could not swim, of course; but neither was it necessary, since the tourists were allergic to water, for obvious reasons; to be considered reckless, it sufficed to bring one’s feet within splattering distance of the sea foam. Those who stood guard attended to giving fair warning to any potential eccentric. Dirt is washed away not with water but with sand baths, as everyone knows.

Despotic women in the abundance of their sagged flesh —and who on account of their age could well have been chamber maids to Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland— walked about most smugly, sporting impossibly tight thongs made of asbestos cloth, stolen from corners for storing extinguishers, grenades, and other stuff. Indeed, pure asbestos swimsuits were all the rage that year.

There were also, however, fairly young girls, elegantly dishevelled and sensually waddling about. No one could tell whether their swarthy complexion owed to the sun, their race, or dirt. I am sorry to say that not all of them were reputable; they felt particularly attracted by fat tramps who wore smoked glasses, drank mate with sugar, and never stooped to take a firebrand for their cigars, exclusively using matches instead. Astonished by such a squandering, the girls regarded these filthy rich men who lit hand-rolled cigarettes and threw away the barely burned, useless sticks, half-closing their eyes in self-satisfaction. These fat men, rotten with tobacco and white sugar, I insist, never smoked a cigarette until their fingers were overburned. They took 13 or 14 puffs and afterwards threw them away.

Hours later, through a twilight of reddish waters, having eaten exquisite blood puddings and sausages, and spicy cheeses roasted on improvised wire grills, these victuals generously sprinkled with a couple of 20 October 1983[2]

vintage wines, their Most Illustrious Wretchednesses, not before straightening their leaden tatters, belly-flopped onto the grass, quite close to the sand, smoking with a sort of pompousness only surpassed by caliphable emirs.

Said Mr. Moyaresmio, as he heaved a long sigh:

“These open-air parties, they remind me of the grimoires effected every now and then by magicians.”

Crk, somewhat drowsy:

“What’s a grimoire?”

“It is a sort of magical, ritual dinner. A great shindy alla grande thrown by the esotericists. There are fine delicacies, exquisite wines, sex, etc. Sometimes they eat nasty things, but they devour them with gusto and ask for more.

Classic grimoires… The only one, as far as I know, was that which another tramp told me about when I was a toddler. It is a long, complex story, of which the grimoire is but one of its incidents; so I do not know if…”

And Mr. Moyaresmio shrugged his shoulders, leaving his back exposed to the free play of the tensions of his filth.

Mr. Crk:

“Proceed, Illustrious. When you began speaking, I got ready to divert some time from my tremendous and overwhelming activities as a magical animal: that is what the Monitor calls us, right?”

“If you are one of those freaks, make a Turkish dancer appear before me.”

“Oh, of course,” promptly answered Mr. Crk, and he scattered a handful of sand into the air, as he said: “In nomine Gromine.”

Naturally, nothing happened. Besides, in a sudden change of wind, the sand fell on Mr. Moyaresmio, making him shed some tears.

Any uncultured man would have uttered an invective. Not Mr. Moyaresmio, who was a Bonapartist aristocrat. He confined himself to saying, as he cleaned up his eyes with a brown handkerchief:

“I have the impression, Mr. Crk, that your magic has failed. A mistake while exorcising, perhaps. Far from materialising what was requested, you provoked a vectorial variation on the sweet Zephyrus. If my judgement is incorrect, I pray that you do not hesitate to refute me.”

“You are absolutely right. I have actually been practising this profession of magical animal for barely forty years. I am still inexperienced.”

The other one, very kindly:

“I understand. It is such an inconvenience.”

“I am coping with it. But you were about to tell me…”

Then, Mr. Moyaresmio Iseka began narrating the “Great Fall of the Indecorous Old Hag.” A while later, this long-drawn story was cut short by Mr. Crk Iseka, who sighed:

“Illustrious…, please. I think it’s enough. When you egg yourself on, you just won’t stop.”

Moyaresmio Iseka:

“It is truly a pity that you have interrupted me. The Sultan did not cut Scheherazade’s head, after all.”

“It’s true. But he did postpone it for the following day.”

“OK, alright,” admitted Mr. Moyaresmio. “In any case, I have spoken much about the qadi already. Enough for you to have an idea.”

“Or many.”

“Notwithstanding, it is a pity. The sacred dogs appear at last, and they gobble —in the famous grimoire— the despicable, arrogant, filthy, nosy old hag. What caviar could be compared to the flesh of a sulphurous chichi, the latter word meaning bad person in my lexicon? Only an allegory may devour another allegory.”

Noticing that his friend remained unyielding and said nothing, Mr. Moyaresmio continued after a gloomy sigh:

“Well, well, alright. Your loss. Unimagined secrets of the grimoire are revealed, on the occasion of the judgement, punishment and obsequies of the astral double of the softened old hag —at last caught red-handed—, when… But anyway, let us leave that aside. In any case —and I warn you, I shall be inflexible on this—, the most I can agree to is waiting until tomorrow, after breakfast, to tell you the surprising and marvellous story N. 948, entitled ‘The clavichord mummy’.”

Reassured to know that he would be saddled with the drag only after a refreshing sleep, Mr. Crk Iseka did resign himself.

Some masses of clouds floated over the sea. Only a few, but dense and white-coloured; increasingly grey within. On the opposite side, from the centre of the Technocratic land, it was dawning. The Sun attempted to rise from behind a far conic tree; surrounded by clouds, rosy with blue fringes, the latter resembled a dessert.

An hour passed. The tree was now an ice-cream crystalled in icy blue and spectral lemon stripes.

Mr. Moyaresmio woke up. He regarded the sky and the horizon with esteem. He lit a fire with a bunch of sticks he had gathered and heated water to drink some mates.

“Mr. Crk… Mr. Crk…”

“Mh.”

“A mate, perhaps? A doughnut with lots of sugar, maybe?”, and in parallel to the offered infusion, he extended with his other hand a disgusting paper sack with shiny contents.

Mr. Crk, taking the mate and a doughnut:

“Saying no to you would be a discourtesy you do not deserve, Mr. Moyaresmio.”

The latter regarded the sky again, for the second time in the day:

“Have you ever thought, Mr. Crk, that certain dawns resemble twilights and some twilights are identical to dawns?”

Teasingly:

“Illustrious… Take no offence, please, but… That phrase was unoriginal even when someone uttered it for the first time. It sounds a lot like: ‘Now the Sun sinks in the twilight’; ‘The clouds swirling like a turbulence of shrouds trying to byyychck!’; ‘The pitcher goes so often to the well that etcetera’; and others.”

“So you find me unoriginal?”

“Absolutely not, Illustrious… But then: if you avoided the cumbersome sequences and went straight to the narration you promised yesterday…”

But Mr. Moyaresmio had his head somewhere else. He even forgot to keep preparing mate, and said absent-mindedly:

“Wait, wait.”

He lit an Egyptian cigarette, held it delicately and decadently with his left hand, and used a stick to draw a tiny rifle on the sand. Then he raised his eagle eyes and noticed an evolving sparrow in the forest of its tree. With the rifle he had just manufactured, he thought, that beautiful specimen of passer domesticus could go hunt some beetles. The coleoptera evolving like rhinoceros from another dimension, facing rifles for bigger game. Bullets ricocheting off the elytra. Bazooka launches harmlessly striking the armour of the Stalin III tank, in Korea: “Another attack like last week’s and they’ll end up jettisoning us into the sea, my sergeant. Take it easy, Benson. MacArthur will come and rescue us.”

“So? The story you were going to tell me?”, enquired Mr. Crk Iseka, drawing Mr. Moyaresmio out of his daydreaming.

“Decidedly, my dear friend, you lack any sense of opportunity. I found myself immersed in a delicious delirium; who knows what magnificent system of the mental arts or architectures it might have yielded.”

“I am sorry.”

“Oh, that is not important,” Mr. Moyaresmio turned his body and remained face up; he resembled a sun-dried clay pharaoh. Impressive, sovereign and majestic, sporting his Puertorimerican sackcloth guayabera and his short socks, made from Virgin Islands-imported silk and tied with telephone cables.

He began narrating, as he regarded the sky for the third time in the day[3]:

“I must warn you: what I will now refer is a tale only in part. With your characteristic perspicacity, I have no doubt that you will be able to discern the truth beyond the dislocation of exaggerations.

There was once a race in mental wheelchairs. They were the epileptics of humour: a shittily solemn bunch, in other words, since they lacked any flexibility for the minimal change of units that would allow them to adapt to anything new and enjoy it. They were like big, floating piles of excrement[4].

When they died, they plopped on the ground. Because I tell you, frigidity in any respect, whether sexual or mental, is a magical disease; just like epilepsy.

This was not a continuous race —like the Jews, Armenians, Baskes or Gypsies—, but a discreet one; their members born as if by mutation from all races. They had accomplished to form a nation, however, and therein they ruled.

Their characteristics were most interesting. Some of them, for instance, became rotten instantaneously in the midst of a conversation, or upon a turn of phrase. See what consequences may have a misused word, or the discordant energy of flawed syntax! When the aforementioned event took place, the individuals of this chichi race went on living, sleeping, eating and copulating, thoroughly rotten, with worms, foul smell and all. Until their flesh began falling off in chunks: first the muscles, then the anatomical pieces comprising the inner organs. The most stubborn ones endured up to the very last moment, eventually collapsing; the small pile was then dragged off to some corner until someone took it away.

They ceased to exercise physical love quite early in their lives, as their sexual organs were the first to undergo annihilation. When the rot manifested —and this always took them by surprise—, they ran off to bed whatever came first, syphilis or leprosy notwithstanding, trying to make up in a few hours for what they had not done in their entire lives. Once castrated, they took to indoctrinating the youth —quite rotten too, for its part— on the virtues of asceticism.”

Crk:

“I have the impression, Illustrious, that you are talking about the Sorias.”[5]

“You delight in interrupting me.”

“What?”

“That you delight in interrupting me, I say.”

“But you are referring to them, right?”

“Maybe.”

Slightly teasing:

“You are a great authority in Soria affairs. I understand that, before calling yourself Iseka, your surname was Soria, right?”

Somewhat annoyed:

“You never miss an opportunity to remind me of my origins.”

Crk turned up the volume of his teasing, for he knew how far he could go:

“Well, they say that you can’t make a silk purse out of a Soria’s ear.”

If Mr. Moyaresmio felt offended, he did not show it:

“I shall repeat what a journalist from Camilo Aldao, a certain village I visited once, said: ‘I am sadly reliable’ to speak about all things Soria. Like I used to be a soria.”

Crk, vibrating his teasing to the continuo harpsichord:

“And are you sure that the Monitor has included you in the exception list, etc.? May I ask you for your metaphysical pardon, sir? Or have you lost it?”

Moyaresmio avoided a direct answer. He proceeded just as if he had not heard him:

“As it happens, if we were Sorias once and ceased to be so, we are not reverting to it. We know very well why we turned away from the chichi. On the contrary, those with the surname Iseka are the ones in grave danger of Soriatising.”

Laughing:

“Well, well. Don’t get me wrong.”

“I am not taking you wrong. I am saying it, that is all.”

“Resume your story, I beg of you.”

“Returning to the characteristics of those floating pieces of shit I spoke about: the primary existential goal of those partial derivatives of the Anti-Being was ruining their antipodes. Each individual in this country knew that in some place, either there or somewhere else, there was a human being whom they needed to —and could— piss off in a clever way, shape or form. When they achieved it at last, having lost the aim of their existence, they fell into an absolute apathy, hastening the process of organic destruction. It was as if the Anti-Being in person had begun to derive those monstrosities from itself, according to innumerable coordinate axes.

Clearly, since these pestilent cusses had very few true enemies, sometimes thousands of chichis had to gather before finding a single common antipode.”

But Mr. Crk Iseka, perhaps due to the heat or some other cause, had ceased to listen. He was raving within: “A Sagittarian dog jumped at my throat. As quick as lightning I gave him an Aries blow with the edge of my hand, and he dropped dead on the Aquarius. Screw you. Screw you per saecula. A Libra spider —its shape mimicked the scale, with oscillating plates around the fulcrum—, its ears adorned with some stolen Leo tassels, solar and refulgent, was approaching me. I prepared to defend myself with the Scorpion’s sting, when my companion yelled: ‘Come on! Shove an electric Pisces up its ass, Mr. Crk!’”

Mr. Moyaresmio Iseka, promptly realising that he was no longer heeded, became furious:

“You’ve stopped listening to me already! You must be thinking about something else!”— he gradually calmed down. “In all honesty, I fail to understand why you ask me to tell you marvellous stories,” he pauses. “And mind you: the swine in my narration always began their rotting like that, becoming inattentive and absent-minded. So, be careful!”, he added sardonically.

Mr. Crk Iseka, fluorescent purple with shame, promised to make up for it and asked his friend to forgive him at least on that occasion. But then he tried to manoeuvre in an uncultured fuchsia colour:

“I just think it would be convenient if you told me at once the surprising and marvellous story of the clavichord mummy, because I get lost with so many twists and turns.”

Moyaresmio:

“Stop making excuses. Apart from that, if I do not describe that people’s idiosyncrasy, you will not understand what happened with the mummy.

In that country, it was remarkable how the chichis sometimes performed acts of justice unwillingly, in spite of the system’s absurdity. It was as if the Being tried to capitalise favourably on misfortune. They went about using catch-all terms and set phrases, and so these became transformed at last into devouring allegories that eviscerated their own creators.

The shortcoming of allegories is that they tend to integrate with the members of the same species. If the addition has enough addends, it becomes the Ultimate Weapon that destroys every civilisation. The only way to put an end to such a state of affairs would be to counter this tumour of diabolical slime with another allegory, stronger and opposite in sign. But that is not possible in a world dominated by the Anti-Being, who kills any opposing allegory in its cradle.”

Mr. Moyaresmio took a break to eat half a salami. He was about to tell other anecdotes about the rottable cusses when he noticed that his friend was beginning to observe the Sun’s position to check the time, as someone raising his wrist to glimpse a gigantic watch. Then, he hastened to say:

“But it is time for me to tell the marvellous and incredible story N. 948, entitled ‘The clavichord mummy’.”

Crk:

“At last!”

[1] All songs and performers mentioned were extracted from the LP: Punto de reunión Munich. B.L.E. Telefunken.

[2] Since that was the day when the first atomic war began, the wine bottled on this date was much sought-after, as it had all the bouquet of the first radiations.

[3] In spite of this, Mr. Moyaresmio should not be taken for a spiritualist. He was observing only the earthly sky, with its twilights and dawns. Limits are the most elevated passion of man; this made of Moyaresmio a normal person, which is in itself a limit too.

[4] Definition of the word excrement, according to the Enciclopedia Sopena, vol. 1, p. 1080, fifth edition, Barcelona, 1933: “…in general, any filthy substance expelled by bodies in a natural way.”

[5] The Sorias were the inhabitants of Soria, a nation with which the Technocracy had been at war for five long years. Both countries’ worldviews were antagonistic. In Soria, everyone had the same surname: Soria, only differing in their first names. Likewise, the entirety of the Technocracy’s inhabitants were surnamed Iseka.

The clavichord mummy

Robert Prescott and Pedro Pecarí de los Galíndez Faisán were Egyptologists and belonged to the discontinuous race of rottable cusses. They were excavating the Valley of the Kings of Music, and also Gizeh. Their objective was to find the tomb of Tutanchaikovsky. They knew that, just like every funerary monument, either large or small, it had been looted by tomb raiders; in many cases, barely an hour after the priests had sealed them.

Legend said that although Tutanchaikovsky’s tomb had been defiled, the sacred objects knocked over, its gold and silver cups stolen —and even more uselessly and sacrilegious: the mummy burned by order of the Shepherd Kings—, it nevertheless contained an invaluable archaeological treasure which successive generations of thieves had left untouched, considering it negligible: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s clavichord.

As I have said, virtually no tomb had been left unvisited by these excellent people: Mendelssohn’s, Richard Strauss’s, Schumann’s. The latter composer’s hands had been cut with an ultrasound gun that emitted an obsessive A, and later the sorcerers bought them from the raiders to prepare magical potions.

Not even Richard Wagner could avoid depredation, despite the two-kilometre-high Great Pyramid he had built for himself, forcing his Nibelungs and the giants Fafner and Fasolt to work under the whip for twenty-seven years: almost the entire span of this autocrat’s reign. The dutiful thieves, with an ingenuity worthy of better purposes, had managed to dig a tunnel in the rock up to the King’s Chamber. They set their hands on the Phantom Solar Boat that pharaoh Wagner used to travel to the Land of the Setting Sun; they knocked his and Cosima’s mummies while dragging them along the galleries to throw them away on the desert. There, under the moonlight, they burned those solid fuels on the Phantom Boat itself.

Nietzsche, much to his chagrin, had been immured with Wagner as punishment for writing Ecce Homo. He was commissioned to guard the composer and defend him in his long journey. To avoid this penalty, he had put forward an ultimately unsuccessful parliamentary motion of obstruction. Before the last row of bricks had been placed, completely sealing off the niche where he lay wrapped in bandages like Christopher Lee, the priests handed him Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Nietzsche’s mummy protected the tomb for a long time. First, he eliminated a band of one thousand eight hundred seventy raiders; forty-four years later, he kicked the shit out of a further fourteen; but when twenty-five years later another thirty-nine guys entered the tomb, he was overcome and burst like a blown-up toad. His potentials had been depleted, and besides the horoscope did not favour the mummy that day. Notwithstanding, he scared the hell out of those who faced him.

The tomb plunderers stole absolutely everything —once triumphant—, and burned the rest. Only the monument and the great stone sarcophagus in the King’s Chamber remained.

Over at Tutanchaikovsky’s the matter was somewhat different, as I anticipated, for the defilers at least left the clavichord.

Robert Prescott and Pedro Pecarí de los Galíndez Faisán ordered their workers to sweep away all the sand from the entrance. Galíndez Faisán himself broke the priests’ seals; they were intact, as the raiders had entered from the other side.

Once inside, they could witness the havoc of looting: the broken tables, the statues shattered, the stone sarcophagus slashed by hammer blows, and above it, the ceiling blackened by the smoke of the burning mummy.

At the end of a dark corridor, partially obstructed by sphynx debris, was the hieroglyph-coated clavichord.

The two expedition leaders began reading:

On whosoever plays this clavichord, wanting in respect or worth, Tutanchaikovsky’s curse shall befall.

Robert Prescott and Pedro Pecarí de los Galíndez Faisán laughed their asses off. They did not believe in curses, in the first place; also: if the curse was so powerful, why did it fail to protect the tomb from the previous raiders? Besides, they wanted to become rich and famous with that clavichord. It had belonged to none other than Mozart himself!

How curious of the predators to have respected that object. Logically, it should have been destroyed with all the rest; at least for the sake of damage, if nothing else. The expeditionaries were unbelievably lucky.

Galíndez Faisán turned on his tape recorder and began playing on the ancient musical instrument.

People would pay in gold to have record plates with the sounds of the legendary clavichord. On it he would perform Mozart’s own compositions, after making some orchestral arrangements, under the slogan: “Mozart, but not for the exquisite.” He could imagine it: “Within the everyman’s reach, with popular arrangements; and besides… on the authentic clavichord, found after thousands of years in a desert-protected sepulchre!”

But what no one knew, neither the tomb raiders before nor the expeditionaries later on, was that inside the clavichord was Mozart’s mummy, stored as a secret weapon. The priests had given the magical order not to intervene, come what may, unless someone played the instrument; because then, whoever did would certainly pay for all. Hence the mummy, filled with rage and helplessness, had witnessed the successive defilements, even the burning of Tutanchaikovsky, without reacting. It awaited the lawful moment to set its hand on one of those guys and torture him endlessly, day and night; after all, that mission was the cause of its own deferred journey to the Land of the Setting Sun. With stiff arms folded over its chest, it prayed: “Oh, Osiris! Lord of the Amenti! Let the hour of vengeance come soon!”

The two chichis, snootified, left the tomb commanding that the clavichord should be kept safe, and making sure at all times that the carriers should not scratch the ideograms inscribed in the mahogany. But —and this was just the first in a long list of inexplicable events— Robert Prescott, who had lagged shortly behind, suddenly disappeared, swallowed by tons of sliding sand that covered the entrance. It was impossible to explain, since the excavation was well-scaffolded.

After said unfortunate slide of sand and rocks, a strange succession of catastrophes ensued. The expedition members died one after the other: mysterious diseases; suicides; guys who claimed to be haunted by mummies at night; others whose walls dripped blood and had to spend the whole night cleaning them, etc.

One of the assistants, Azafrano Capitular Mileto, deeply worried, went somewhere to have his astral chart drawn. According to the astrologist, the stars revealed that his death would be caused by a dog. Azafrano considered such a thing to be quite possible: he lived in a neighbourhood packed with those animals, all of them thoroughly wicked. To keep himself safe until he moved away, he fashioned a sprayer loaded with mineral oil and pepper. With it he felt secure.

One night —he was moving in a few hours and so took full precautions— he was returning home with the sprayer out of its holster, like Flash Gordon, since the next door belonged to a building with two dogs worse than Cerberus which had previously torn some pieces from his clothes. He proceeded, ready for action and blowing an imaginary whistle to signal his invisible troops forward (Kirk Douglas, Paths of Glory).

However, the unscrupulous canines gave no signs of life. They must have been taken to a doghouse or maybe they were sleeping.

Azafrano Capitular Mileto sighed with relief. Precisely when he said: “Ah! Thank God!”, a monstrous gargoyle broke off from a building and shattered his head. It is almost unnecessary for me to say that said gargoyle had the shape of a dog.

Pedro Pecarí de los Galíndez Faisán, for his part, had long ceased to laugh. Barely two months had passed since the opening of Tutanchaikovsky’s tomb, and he was the only one who remained alive. He donated the clavichord to a museum so that he might avoid the curse, but it was useless: at night, his mansion became full of groans and strange noises, like the gnashing of giant teeth or someone dragging a huge fork along the corridors. He did not know why, but he felt it was no other object than that.

The sale of record plates had made him rich and famous, though not everything was in his favour. He hired ten bodyguards to keep watch day and night; he had his car’s brakes and steering checked before driving, etc.

One midnight he had an abrupt awakening. He hallucinated that his bodyguards were sleeping. He got up to investigate and, indeed, he was right. So profound was the narcotic commotion of that magical sleep that kicking them was futile.

Utterly shit-scared, he tried to run to his bedroom and lock himself in. Yet those terror-infused jinxes made him trip over his own feet again and again, so it took him exceedingly long to arrive and close the door.

He had hardly sighed when he heard a whisper at his back. He turned around, suffocated, and from behind a red curtain appeared the bandage-wrapped Mozart, with all the might of his braid—the famous braid itself, with a large black bow, hanging from the nape and sticking out between the linen cloth. He was wielding a huge fork in his right hand, its tip somewhat tilted towards the floor, at rest, like a reposing god.

“I’ve been waiting so long to get you, motherfucker.”

After this phrase, he began plodding very slowly, calmly elevating the fork’s tines. The mummy seemed extremely tall, like three meters high, and yet it was no taller than when it was alive.

Pedro Pecarí de los Galíndez Faisán let out a moan, hampered by brakes and exhaustions he could not manage to explain. It was as if the air had turned into a viscous fluid filled with ground glass, imposing friction and strong bonds. Walking felt painful. Most uncomfortably, with delay and tardiness, he reached at last the stairs connecting to the ground floor. He descended without using the steps: smoothly floating over a thin layer of sticky air. He did move, but with each minute lasting longer than the one before. Now approaching the last steps, he stopped briefly to see his pursuer’s progress. That nightmare of a mummy was getting ready, right at that moment, to start after him. And so it came down just like the Pale One should, with its large naked feet and the long white shroud, heavy as the curtain of an opera theatre; sometimes it seemed to smile. The mirage of a smile was turned on and off intermittently, through the bandages’ alternating chiaroscuro. He saw the mummy in flotation, squalid and trotting on the wind, with the bare fork. It flew silently, similar to hovering roc birds impelling large air masses; or heavily pushing the waters, like a huge manta behind the frogman.

Pedro Pecarí Galíndez reached the last steps and floated like dust over the hall’s flooring, resuming his clumsy lunar walk. The very invisible vapours that sustained him at a height oscillating between five and ten centimetres made him sticky, hindering his march.

He drifted aimlessly, in geometric figures. If he traced an ellipse, the mummy —always hounding him— drew a parabola arm. If he designed a sine wave, the mummy limited it between the two parts of a hyperbola. A cardioid was immediately answered by a perfect, lethal circumference. It was like the ending of Don Giovanni, but the other way round; instead of the stone guest coming in search of the lover, the allegory was inverted here: Don Juan’s statue was approaching to kill the evil and prejudiced Commendatore, just when the latter was in the business of ingesting various tasty victuals.

At moments, during his marches and contredanses, Pecarí Galíndez Faisán stooped to the ground; but it was worse then: it felt like wearing metal shoes on a floor with some powerful electromagnetic field. By no means could he lift his footwear then. He was barely able to shuffle his feet pitifully.

He tried to find the entrance door, but it was blocked by a white wall that bounced him off with each attempted approach.

He stepped back, tremulous and convulsed, always confusingly linked to the ground. His grotesque puppet legs did not cease to pester him with their clumsiness, as the enemy doubled his monstrously and materially obsessive harassment.

Coming out of the hall, he reached other regions of the house.

In slow motions he wandered around the corridors, transformed into formidable avenues. All of their labyrinthine, spiralled turns did nothing but bring him back into the entrance hall, at the foot of the staircase. He went up again, always chased by that Minotaur.

The short three-metre stretch between his bedroom and the staircase resembled an appalling motorway bursting with cars. He crept along, moist as a toad, semi-paralysed and panting. Just about to close the door, he confirmed once more what by now he knew for sure: seeking refuge there was useless, as the dazzling mirror of death was waiting inside. The end-tree lost its crystals, slowly torn down to luminous shreds. These, its last days, sank deep into the bejewelled borders and lavish limits of the sarcophagus of eternal discontinuity. The princely, military poverty of Death raised martial oriflammes, austere war banners and bellicose black flags. The waters of consummation rose. The batrachian fled, chased by harsh crane flapping white. Androgynous splashed from one puddle into another, now resplendent tiger’s four fangs too close. Squashy fat one tender and flaccid, trotting over a thin film of astral dust; extended over him dazzling snowy heavy hand. Before him reverberated iridescent mortuary reflections as of a shutting trap. He felt as if stepping on steppe lichen or the orients of frozen jewels.

Once again he floated downstairs, on a rectilinear trajectory. The mummy, he understood, was waiting below, although it was behind but a few seconds before. Faisán descended over the tips of the four-tined fork, resembling a projectile whose course someone forgot to deviate. With a most violent effort, he modified his path slightly. He touched ground with his feet, after one skewer had gone a few millimetres past his thorax.

For a long while it went on like this, coming and going to and fro, with Faisán unable to get rid of his pursuer and the mummy unable to reach him.

He understood how absolute is the fact of dying for real. Notwithstanding, so wretched was he that somewhere in his soul he rejoiced. He was the man who had said some time ago: “Life is hard. Luckily, we have our own masochisms to keep ourselves entertained.”

Keep yourself entertained now, Soria.

Masochists are not eager to die, but to be castrated and dumped in a ditch. And to live for a very long time, whining at all times. Or to have their hands cut, or to be blinded. Or to get themselves killed, in any case, but dying a protracted death. That is why people should not be castrated, but stabbed with a fork.

“Quick deaths are the worst,” said Mozart, almost grazing him.

In an attempt to escape, in his despair, Faisán became fragmented into eight pheasants, so that at least one of them could flee. The entire flock fluttered inharmonically, stiffly, beset by eight mummies. Then he became divided into twenty, thirty-five, n Pedros Pecarí de los Galíndez Faisán, and there were n fierce mummies pursuing them.

Having arrived at the last wall, the definite wall, all the pheasants fused into the one true chichi again, transformed into an agitated, gasping chicken. And from remote sideral distances, lightyears away, the n distant mummies, each wielding a fork, gradually converged on this sole point, while in the vicinity of his chest they joined with each other, and so did the ethereal additive coordinates of the weapons until

they constituted but one solid, lethal object. The materialisation took place four centimetres away from Galíndez Faisán’s chest. And the fork came slowly closer, the tips penetrating painlessly at first, as if they were frozen humours.

The fork tines stabbed him like four magical words, or four operas.

Horror and pain. Horror and pain for Faisán. And it pierced through him like a golden chicken, leaving him nailed against the now wooden entrance door, without the white wall, and which at some point had been impossible to open.

Thus he was found the following day. With that immense silver piece fastening him to the door.

The serpent Kundalini

Monitor, in his infinite wisdom, made a decision regarding some man. He had him tortured using the most expensive method that has ever existed.

Building the torture machine required extracting no less than fifty thousand million cubic metres of earth, sand, and rocks; that is, a little more than fifty cubic kilometres. Steel beams, high-pressure resistant planks, cables, cement, etc., comprised the body of the cavernous monstrosity.

Only the Technocratic power could achieve it, especially considering how much it took to work on its construction, which was under two years.

The device consisted, among other things, in a two-thousand-metre-deep pit; its bottom gave way to a long five-thousand-kilometre-long tunnel, characterised by becoming imperceptibly curved towards the left. Thus, its circuit finished right at the beginning, tracing a perfect circumference. It was like a serpent biting its own tail.

The walls, both the pit’s and the tunnel’s, were initially much larger, as it was necessary to set some space apart to lay reinforced concrete, beams and planks, meant to withstand the immense pressures.

To grasp the gallery’s giant dimensions, there is nothing better than imagining how damped its curvature was.

The tunnel was accessed by descending through the long pit in an elevator equipped with solar batteries. Whenever someone marched through the long five-thousand-kilometre passage, a set of lights turned on ahead and off behind. Thus, the walkers were constantly travelling within a hundred-metre-long, permanently mobile luminous volume.

The lamps had been so designed as to render the tormented unaware of the tunnel’s curvature, which would have been perceptible, however slight the deformation, if the lengthy expanse had been illuminated in its entirety.

Every few metres there were food and vessels with water. When the walker felt tired and drowsy, he could simply lie down and sleep in the torturing passage.

The condemned, though perfectly alone, felt the Monitor’s presence. Knowing him quite well, he had reason to suspect that, at a certain unknown point of the prolonged cavity, there would be some trap awaiting him: a fatal, hope-shattering cul-de-sac, or a torture chamber filled with eager executioners, or anything else.

All of this could be expected from the Monitor’s mentality, but in this case he felt it would not be exactly like that. “He’ll surely have me wandering for years, until I end up discovering that I’m once again at the beginning and become mad.” He had come up for the first time with the idea that he might be marching along the perimeter of a circumference. A dot moving along an elementary and inflexible succession of dots. By all accounts, he must have been less than an abstraction in the Monitor’s mind at that point.

This did coincide with his idea of the Head of State’s all-encompassing thought when he felt like being subtle.

“Every section of this sort of coal mine is the same; however, when I eat and drink I’ll leave marks,” he argued. He imagined himself much later, thinking upon seeing scraps on the floor: “Someone else seems to have been here months ago,” misunderstanding the building’s true character, just to discover, over time, something which no one but he could have left, as the exact nature of his punishment dawned on him with horror. All of this he supposed in a convulsion, no longer walking, immobile due to his membrane-covered atavistic fear.

Pretending to tie his shoelaces, he stealthily left his watch on the floor. If he happened to return, as suspected, he would find it. He tried to attract attention to himself and away from the watch, in case someone was observing him.

Each day he covered ten kilometres. Sometimes he lost his mind, goose-stepping in a fit of anger until he became exhausted. Other times, he broke into a run as if he were to be boiled alive: hurting himself against the walls like Professor Otto Lidenbrock’s nephew in Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth. So possessed was he by the memory of this book that he yelled, adding bump after bump on his head and foaming at the mouth: “Saknussemm! Saknussemm!”; collapsing at last, exhausted. “I adore you Graüben, why do you flee?”

Sometimes he flatly refused to keep going. Sitting on the floor, bursting with mental electricity and earthing, he set out to return to the starting point after some rest, or else remain there per saecula. On those occasions, he soon felt the inner warning that carrying on was his only prospect of salvation; falling prey to nihilism would entail his doom. Little by little he disciplined himself—something he had done only occasionally during his life. Besides, why go back if he had eaten and drunk the entire content of the vessels?

Perhaps they would be refilled in case he completed the entire revolution, but not if he turned back now. Not without reason the food and water vessels in each station contained exactly what he needed to become full, but nothing more.

He kept walking. A sole idea sustained him now: finding his watch to prove that the passage bit its own tail. That is, he managed to reverse the torture; what was meant to torment him became transformed, by virtue of his will, into his main support.

Five hundred days after setting out on his march, he found his watch. He did not think: “So now what?”; he did not ponder on the long tunnel, with steel planks like the scales of a serpent biting its own tail. He discovered, however, that he was in the house of some God. He sat on the floor and did the lotus position before his jewel. Bejewelled platinum measured the time; the last fraction of the definitive second was a coloured spiral over discontinuous white rails.

He attained the state of Samadi, or illumination.

Seeing him thus, the Monitor had him released and gave him a high office. Until the end of the war, he was his Minister of Propaganda.

Technocracy. Monitor. Triumph.

Leave A Comment