Eduardo Gudiño Kieffer

Selected stories from

Fabulario (1969) (I)

Link to part II:

E. Gudiño Kieffer: Selected stories from “Fabulario” (1969) (II)

Link to my commentary on the translation:

Commentary on the translation of “Fabulario”, E. Gudiño Kieffer

Eduardo Gudiño Kieffer

Herein you shall find the stories I chose in their original language, followed in each case by my translation into English. I would specially like to thank translator and professor Magalí Libardi for her help in revising my translations. I recommend visiting her excellent and most interesting blog, Nota del traductor.

Fabulario

Otra versión de la Caída

Ellos, al fin, después de muchas experiencias antropomórficas frustradas, resultaron lúcidos y responsables; hermosos según los cánones de quien los había creado a su imagen y semejanza; inteligentes y libres y vagando a su antojo por el enorme jardín del Cuarto Cielo. Felices al ver el regocijante candor amarillo salpicado de flores oscuras que ostentaba mimosamente la pantera; felices bajo el encaje verde de los árboles, junto al azul lavanda de los estanques; mirando quizás los espléndidos dibujos de las nubes con sus dobladillos de nácar; jugando con cristales de cuarzo; metiendo los dedos en geodas de sílice o los pies en el barro; ignorando su dicotomía original; gozando sin saberlo de una plenitud fálica y tierna y desmesurada y sin dogmas ni versos ni veredictos. Felices sin conocer siquiera la palabra felicidad —cuando la felicidad es un hecho a nadie se le ocurre pensar en ella—. Además, ignoraban la comprometedora denominación de “homo sapiens” que alguien les adjudicaría más adelante, y esa ignorancia los eximía de verbos tan difíciles y odiosos como hacer, trabajar, razonar, orar o filosofar.

El primer hombre y la primera mujer —porque de ellos estamos hablando—, se alimentaban de ambrosía, néctar tan noble que, además de acariciarles melifluamente la garganta y el paladar, descendía en cascadas por sus gargantas, lea daba fuerzas, les conservaba la salud y no les causaba ni el menor trastorno gástrico o digestivo, puesto que se eliminaba a través de los poros, en aromadas ráfagas que iban a mezclarse con el opulento perfume de las rosas y la urgente fragancia de los jazmines. La vida era realmente perfecta y el cuerpo ámbito dé placeres siempre nuevos, siempre intensos, siempre vehementes, nunca molestos. Jamás picazón, estornudos o hemorroides. Pero —sí, aquí está el “pero” que todos aguardaban—, en el Jardín del Cuarto Cielo crecía un árbol, de cuyos frutos el primer hombre y la primera mujer tenían prohibido servirse. Posteriores y muy teológicas discusiones llenaron bibliotecas enteras de folios que trataban sobre la especie de aquel árbol. ¿Manzano, plátano, membrillo? Nada de eso: era un árbol de galletas. Doradas, tentadoras, crujientes galletas pendían de sus ramas. Galletas frescas, calentitas, con un olor que trastornaba la mente y el estómago… Y he aquí que el primer hombre y la primera mujer, cansados quizás de tanta inefable ambrosía, no pudieron resistir el impulso y comieron del fruto prohibido. Fue un inquietante estremecimiento, un mordisco primero taimado y después rotundo, una cosquilleante sensación en el filo de los dientes, en las encías; un insospechado modo de adquirir consciencia de la piel, de los huesos, de las uñas y de los pelos. Todo fue hermosísimo durante unas horas; aparentemente nada en el Jardín del Cuarto Cielo había cambiado —salvo que los árboles parecían un poco más verdes y los gritos de los monos y de los guacamayos más agudos—. El cambio, el verdadero cambio lo empezaron a notar cuando presintieron que las galletas no se eliminaban como la ambrosía, que el camino de los poros no parecía funcionar para un alimento tan sólido y prosaico. De pronto se encontraron dueños de la sabiduría, y la sabiduría misma les estaba diciendo que los ruidos que sentían en las cañerías internas del cuerpo, los gorgoteos y las flatulencias, presagiaban extraños acontecimientos; que las sonoras y fétidas emanaciones involuntarias no tenían nada que ver con el Jardín del Cuarto Cielo ni con lo que ellos habían sido hasta comer las galletas del Árbol de la Ciencia. El cuerpo, ese querido cuerpo tanto tiempo fiel, los traicionaba. Y sin querer empezaron a gritar palabras cuyo significado desconocían; ¡por favor un retrete, dónde está el excusado, watercloset, petit coin! Empezaron a correr profiriendo las palabras misteriosas, que provocaron rosados vuelos de flamencos y huir de liebres entre los setos. Así llegaron ante el Ángel de la Espada Flamígera y reclamaron eso que ellos mismos desconocían. El Ángel los miró con desprecio y conmiseración, y al tiempo que señalaba con la espada de fuego un lejano punto en el espacio, dijo: —¿Veis aquel pequeño planeta, grande como nada, que está a unos sesenta millones de kilómetros de aquí? Pues bien: es la Tierra, retrete del Universo. Id lo más rápido posible y quedaos allí; es el sitio que os corresponde…

Y ellos vinieron. Y comprobaron que las cosas no eran como allá arriba. Hacía frío, hacía calor, llovía; los mosquitos se habían vuelto crueles; los leones los atacaban y los pájaros les temían. Pero pudieron expedir tranquilamente las galletas. Fue el vértigo, el éxtasis, la liberación, el delirio. Fue también el perpetuo deseo de repetir la experiencia.

“Gracias a la galleta entramos en la Historia. Y gracias al proceso digestivo de la galleta tenemos conciencia de nosotros mismos.”

Another account of the Fall

They, at last, after sundry frustrated anthropomorphic experiences, turned out to be lucid and accountable; beautiful by the canons of Him who had made them in His own image; intelligent and free and roaming at will the vast garden in the Fourth Heaven. Happy to see the panther, flaunting in cuddles its rejoicing yellow paleness splattered with dark flowers; happy below the green canopy of the trees, by the lavender blue ponds; perhaps regarding the splendid drawings in the clouds, with their nacre hems; toying with quartz crystals; sticking their fingers in silica geodes or their feet in the mud; ignoring their original dichotomy; unknowingly enjoying a fulfilment at once phallic and tender and unbridled and lacking dogma or verse or verdict. Happy without even knowing the word happiness —when happiness is a fact, nobody bothers to think of it—. They also ignored that compromising label of “homo sapiens”, which later on would be applied to them, their ignorance relieving them of such difficult and dreadful verbs as making, working, reasoning, praying, or philosophising.

The first man and the first woman —for it is them we are referring to—, lived on ambrosia, such a noble nectar that, besides mellifluously caressing throat and palate, cascaded down their throats, made them strong, kept them in good health and induced not the least gastric or digestive discomfort, since it was released through the pores, in scented gusts which melded with the lavish perfume of roses and the urgent fragrance of jasmines. Life was indeed perfect, and the body, a field for pleasures, always new, always intense, always vehement, never upsetting. Never an itch, a sneeze or haemorrhoids. But —yes, here is the “but” everyone was waiting for—, in the Garden of the Fourth Heaven there grew a tree, the fruits of which were forbidden for the first man and the first woman. Later and very theological discussions filled entire bookshelves with folios on the species of such tree. Apple, banana, quince tree? None of that: it was a cookie tree. Browned, tempting, crunchy cookies hanged on its branches. Fresh, warm cookies, with a mind- and stomach-disrupting smell… And so the first man and the first woman, tired perhaps of such unspeakable ambrosia, could not resist the impulse and ate the forbidden fruit. It was an unsettling thrill, a surreptitious bite first, outright afterwards, a ticklish feeling in the edge of the teeth, in the gums; an unexpected way of becoming conscious of the skin, of the bones, of the nails and of the hairs. Everything was most beautiful for a few hours; it seemed nothing had changed in the Garden of the Fourth Heaven —only the trees seemed somewhat greener, and the shouting of monkeys and macaws, shriller—. They noticed the change, the true change, when they felt that the cookies would not be expelled like ambrosia, that the pores seemed not to work for such a solid and prosaic food. All of a sudden, they possessed wisdom, and wisdom itself told them that the noises they felt in their inner, bodily waterworks, the gurgles and the flatulence, foretold of strange occurrences; that the audible and foul unintentional vapours had nothing to do with the Garden of the Fourth Heaven, nor with anything they had been until eating the cookies of the Tree of Wisdom. The body, that dear, long-faithful body, betrayed them. Inadvertently, they began yelling words the meaning of which they ignored: please a toilet, where is the latrine, water closet, petit coin! They dashed away uttering the mysterious words, which caused rosy flamingo flights and escaping hares among the bushes. Thus they arrived before the Angel with the Flaming Sword and asked for that which they ignored. The Angel regarded them with contempt and commiseration, and pointing at a distant spot in space, he said: —See ye that small planet, as big as nothing, some sixty million miles from this place? Well now: that is the Earth, the toilet of the Universe. Go as fast as ye can and remain there; that is where ye belong…

And so they came. And they noted that things were not as up there. It was cold, it was hot, it rained; the mosquitoes had become cruel; the lions attacked them and the birds feared them. But they could easily excrete the cookies. It was vertigo, ecstasy, liberation, delirium. It was also the perennial desire to repeat the experience.

“Thanks to the cookie, History was born. And thanks to the digestive process of the cookie, we are conscious of ourselves.”

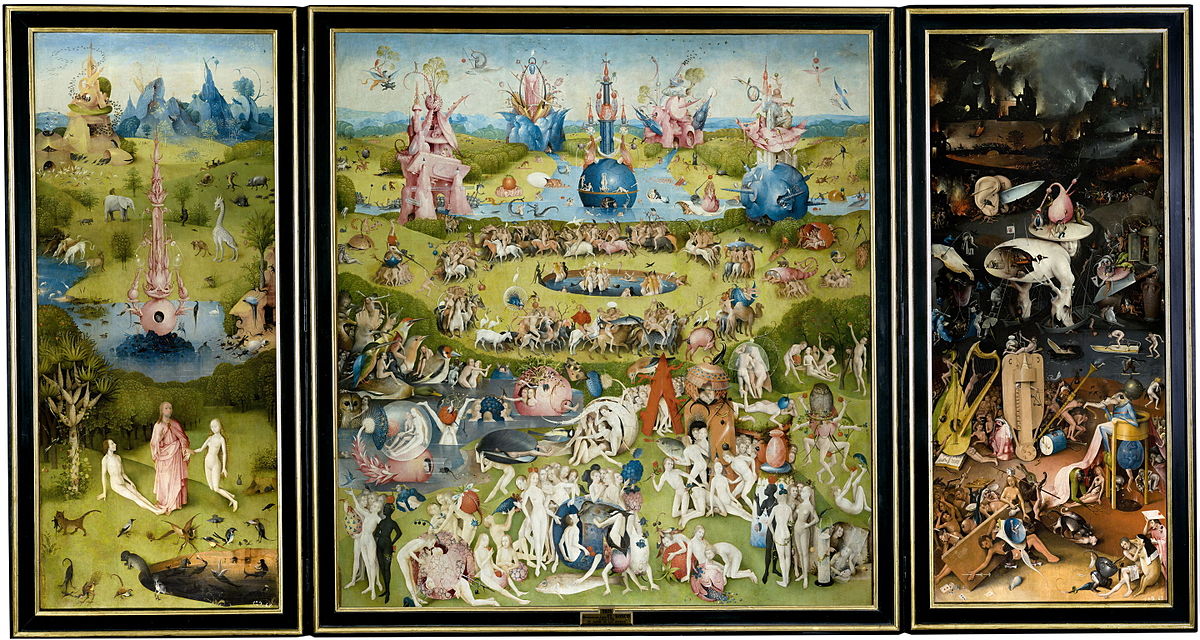

The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymus Bosch

El Faunito

Mientras el Faunito vivió sin vislumbrar la vida (tocando la siringa, comiendo uvas silvestres y durmiendo al sol), todo fue maravilloso. Una corona de pámpanos bastaba para embellecer la jomada. ¡Y era tan inquietante correr por los vericuetos del bosque persiguiendo su propia sombra; o tratando de atrapar la idea de una idea, concretada a veces en cabellera al viento, risa de agua, muslo terso o silueta fugitiva! Sí, el Faunito era feliz. Feliz porque sí, feliz sobre todo cuando tocaba el instrumento que él mismo había construido con unas cañas cortadas junto a la fuente de Castalia: la siringa de la que arrancaba lamentos, arrullos, voces y hasta palabras (o quizás todo lo que no podían decir las palabras). Tan arrebatadora era la música del Faunito, que para escucharla los peces salían del agua junto a las náyades húmedas, las dríades abrían los troncos de las encinas milenarias, las lobas amamantaban a los corderos, de entre mirtos y laureles asomaban silvanos desmelenados. Pero (no sólo lógica sino también mitológicamente) felicidad que dura… deja de ser felicidad. Un día Filomela, estremecida por la música del Faunito, voló tan alto que chocó contra el carro de Apolo: —“¿Qué haces aquí, tan lejos de tus bosques?” —preguntó el dios.— “¡Vuelo en alas de la música del Faunito!” La respuesta, por supuesto, desagradó a Apolo, que tomó su lira de oro y descendió hasta el umbrío lugar donde un simple faunito se permitía hacer música que impulsaba a los pájaros al cielo. ¡Ah! ¡Hubierais debido estar allí para escuchar tan formidable contrapunto! Al primer acorde de la lira, los árboles temblaron. Pero al primer gemido de la siringa derramaron lágrimas verdes. Al primer acorde de la lira las fuentes enmudecieron, pero al primer gemido de la siringa dejaron de manar. Euro llevó los sones al Olimpo. Al escucharse la lira de Apolo se interrumpió uno de los divinos banquetes. Pero cuando se oyó la siringa Ganimedes volcó la copa sobre la túnica de Zeus, que por azar no estaba en ese instante transformado en animal para seducir a alguien. Apolo acabó por darse cuenta de que la música del Faunito era muy superior a la suya. Y decidió vengarse como sólo los dioses saben hacerlo. Dejó caer la lira con desgano, y señalando los pies del Faunito empezó a reír a carcajadas. Los dioses, asomados a balcones de nubes, miraron hacia donde señalaba Apolo y rieron también. Y rieron las ninfas y las dríades y las náyades y las lobas y los corderos y los pájaros y los árboles y las piedras. El mundo estalló en una infame risotada. El Faunito bajó los ojos. Recién entonces descubrió que tenía patas de chivo.

“No desafíes a los dioses, so pena de descubrir que tienes patas de chivo.”

The little Faun

While the little Faun lived without discerning life (playing the syrinx, eating wild grapes and sleeping under the sun), everything was wonderful. A crown of grapes sufficed to embellish the day. And it was so unsettling to run around every turn of the woods, chasing his own shadow; or attempting to catch the idea of an idea, sometimes realised in hair in the wind, watery laughter, smooth thighs or fugitive contour! Yes, the little Faun was happy. Happy just because, happy more than ever when he played the instrument he had fashioned himself with a few cut reeds by the fountain of Castalia: the syrinx from which he would tear laments, lullabies, voices, even words (perhaps everything words spoke not). So enthralling was the little Faun’s music, that the fish and the wet naiads would come out of the water, the dryads would open the trunks of thousand-year-old oaks, the she-wolves would suckle the lambs, from among the myrtles and the laurels appeared sylvans with ruffled hair. Yet (not only logically, but also mythologically) enduring happiness… ceases to be happiness. One day, Philomel, shuddered by the little Faun’s music, flew to such heights that she bumped into Apollo’s chariot: “What are you doing here, so far from your woods?”, asked the god. “I fly upon the wings of the little Faun’s music!” Naturally, the answer upset Apollo, who took his gold lyre and descended to the shady place where a mere Faun dared make music which moved the birds in the sky. Oh! Had you been there to appreciate such an admirable counterpoint! At the first chord of the lyre, the trees shook. But at the first moan of the syrinx, they shed green tears. At the first chord of the lyre, the fountains fell silent, but at the first moan of the syrinx, they ceased to flow. Eurus took the sounds to Olympus. Upon the sound of Apollo’s lyre, one of the divine banquets was interrupted. But upon the sound of the syrinx, Ganymede spilt the glass on Zeus’s tunic, who, by chance, was not then transformed into some animal to seduce someone. Apollo came to realise that the little Faun’s music was outright superior to his. So he decided to take revenge as only the gods know. Reluctantly dropping the lyre, and pointing at the Faun’s feet, he burst into laughter. The gods, leaning on cloudy balconies, looked where Apollo pointed to and laughed too. And the nymphs and the dryads and the naiads and the she-wolves and the lambs and the birds and the trees and the stones laughed. The world burst into an infamous guffaw. The little Faun lowered his eyes. Only then did he discover his goat legs.

“Never defy the gods, lest you should discover you have goat legs.”

Diana and her Nymphs surprised by the Fauns, Peter Paul Rubens

Paracélsica

Quizás porque adivinaba la ambigüedad de la naturaleza, germen de transformaciones perpetuas y perpetua transformación en sí misma, Paracelso encontró a su propio yo en una estatua.

La historia comenzó en Basilea, bajo las frígidas estrellas azules, luego de una agotadora jornada quemando libros clásicos de medicina y gritando en alemán su esotérica teoría del “astrum in corpore”, tan difícil de aceptar para los burgueses y los escolásticos enceguecidos.

Esa noche Paracelso vagaba sin rumbo, pensando en alquimia, panaceas y espíritus ígneos o acuáticos, y preguntándose si valía la pena convencer a los hombres de su estrecha relación con el orden cósmico total. Caminaba por una estrecha calle, cuando una puerta abierta le llamó la atención. Parecía que lo invitaba a entrar en el oscuro corredor. Y dejándose guiar por las fuerzas tenebrosas, Paracelso se internó en las sombras, tanteando las paredes para no tropezar en el piso desigual, hasta que divisó, luego de un recodo, la luz mortecina de las siete velas de un candelabro. El candelabro estaba en una habitación cuadrada, alta y sin ventanas. La amarilla luz temblequeante mostraba una estatua, quizás modelada en cera, en la que Paracelso reconoció cada uno de sus rasgos, sus propios ojos alucinados, las venas verdosas que surcaban sus largas manos flacas. No se sorprendió: todo podía suceder y, sin duda, todo sucedía. Se dedicó pues a examinar con atención la estatua, vestida también como él, con un ropón basto y humilde. Forzando la vista notó que sobre la frente, escritas como por la levísima punta de un alfiler, se destacaban unas palabras: “phantasia, imaginatio, speculatio, agnata fides”. Siguió observando minuciosamente y en el dorso de la mano que la estatua tendía pudo descifrar algo más: “Soy tan grande como Dios; Él es tan pequeño como yo; no puede nada sobre mí; yo bajo Él nada soy”. Paracelso leyó la frase una, dos y tres veces. Después alzó los ojos, porque presentía que la sonrisa de la estatua le estaba dirigida. Y, al sonreír a su vez, aceptó la transmutación; sintió entonces cómo su cuerpo se iba enfriando, endureciendo e inmovilizando, y vio como el que fuera estatua cobraba vida y se alejaba hasta desaparecer por el largo corredor, llevándose para siempre sus dudas y sus convicciones, dejándolo solo y mudo y por fin eternamente unido a sí mismo.

Los que después fueron sus discípulos, los que lo amaron, los que lo odiaron, los que lo vilipendiaron, los que lo ensalzaron, nunca supieron que el verdadero maestro era una estatua inmóvil en una casa secreta de Basilea, y que quien les brindaba tanta filosofía sagaz, tanta inquietud astrológica, tanta magia y tanta sabiduría… era nada más y nada menos que una estatua de cera atormentada y tal vez mortal.

“Alterius non sit, qui suus esse potest.”

Paracelsica

Perhaps because he surmised nature’s ambiguity, origin of perpetual transformations and perpetual transformation in itself, Paracelsus found his own self in a statue.

The story began in Basel, under the freezing blue stars, after an exhausting day burning classical medicine books and crying in German his esoteric “astrum in corpore” theory, so hard to accept for the bourgeois and the blind Scholastics.

That night Paracelsus wandered aimlessly, pondering on alchemy, panaceae and fiery or watery spirits, and doubting the worth of persuading men about their intimate relationship with the entire cosmic order. He was strolling along a narrow street, when an open door caught his attention. It seemed as though it invited him into the dark corridor. And letting dismal forces guide him, Paracelsus penetrated the shadows, feeling his way to avoid tripping on the uneven floor, until he glimpsed, past a bend, the dim light of the seven candles of a candelabrum. The candelabrum was in a tall, windowless square room. The trembling yellow light showed a statue, perhaps made of wax, in which Paracelsus reckoned each of his features, his own delirious eyes, the greenish veins traversing his long, skinny hands. Surprised he was not: everything could happen, and indeed, everything did happen. He took, then, to closely examining the statue, also dressed just like him, with a humble, coarse robe. Squinting his eyes, he noticed on the forehead some recognizable words, written as with the minute tip of a pin: “phantasia, imaginatio, speculatio, agnata fides”. He kept carefully looking and, on the back of the statue’s outstretched hand, he could decipher something else: “I am as great as God; He is as little as me; He can do nothing above me; I am nothing below Him.” Paracelsus read the phrase once, twice, thrice. Then he raised his eyes, for he felt that the statue’s smile was dedicated to him. And by smiling back, he accepted the transmutation; hence, he felt his body become cool, stiff and immobile, and saw him who was a statue become alive and go away until disappearing along the corridor, taking forever his doubts and certainties, leaving him alone and mute and at last eternally joined to himself.

Those who would afterwards be his disciples, those who loved him, those who hated him, those who vituperated him, those who praised him, never knew that the true master was a motionless statue within a secret house in Basel, and that him who brought them such a shrewd philosophy, such astrological restlessness, such magic and such wisdom… was nothing but a tormented, and perhaps mortal, wax statue.

“Alterius non sit, qui suus esse potest.”

Leave A Comment