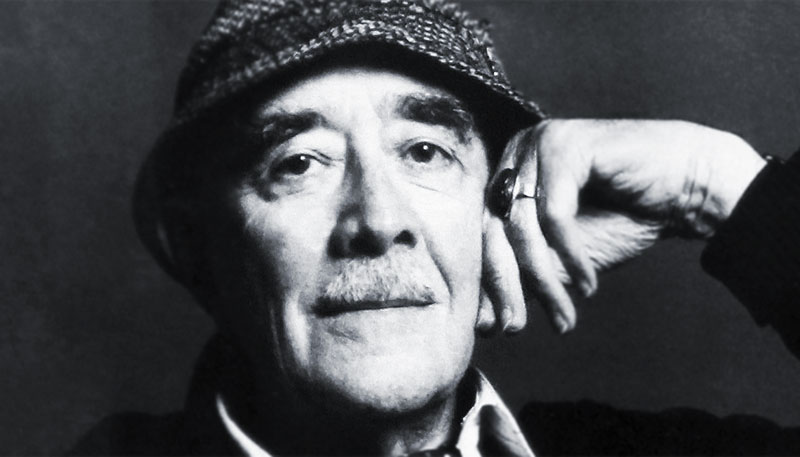

Manuel Mujica Láinez

Selección de cuentos

de Misteriosa Buenos Aires (1950)

Vínculo al texto original:

Vínculo a la segunda parte:

Manuel Mujica Láinez: Selección de cuentos de Misteriosa Buenos Aires (1950) (II)

Manuel Mujica Láinez

“A mí se me hace cuento que empezó Buenos Aires. / La juzgo tan eterna como el agua y el aire.” (Jorge Luis Borges, “Fundación mítica de Buenos Aires”). Puede resultar curioso introducir las traducciones de estos cuentos de Manuel Mujica Láinez con una cita de otro autor (aunque sea Borges, nada menos); pero creo que no hay mejor manera de describir el imaginario que me transmitieron cuando los leí por primera vez, hace tantos años. Hoy, tras descubrir con asombro que esta obra no ha sido traducida al inglés, vuelvo a ellos para hacerle justicia a su autor, con esta humilde traducción de unos poquitos cuentos. Tómese como el agradecimiento de un lector a un escritor, por haber regalado sus historias y sus fantasías.

Misteriosa Buenos Aires

I

The Hunger

1536

Around the uneven palisade that crowns the plateau facing the river, the Indians’ bonfires crackle day and night. In the starless darkness they are even more frightful. The Spaniards, carefully posted among the trunks, watch in the brilliance of the bonfires, unbraided by the wind’s madness, the dancing shadows of the savages. From time to time a gust of icy wind, penetrating the clay and straw hovels, brings along yells and war songs. And soon resumes the rain of flaming arrows, their comets illuminating the barren landscape. During the truces, the groans of the Adelantado, who never abandons his bed, add terror to the conquerors. They would have desired to take him out; to drag him on his litter, brandishing his sword like a madman, towards the ships nodding past the tufa beach, unfurl the sails and escape from this damned land; but the Indian siege prevents it. And when it is neither the besiegers’ cries nor Mendoza’s laments, it is the anguished begging of those eaten away by hunger, their complaint growing like the tide from below those other voices, the beating gusts, the discrete arquebus shots, the crackle and collapse of burning buildings.

Thus have passed many days; several days. They have ceased to keep count. Today there is no crust of bread to partake of. Everything has been snatched away, torn, ground: the meagre portions first, then rotten flour, rats, filthy bugs, the leather of boiled boots which they sucked on desperately. Now chiefs and soldiers lie all over the place, by weak fires or close to the defence stakes. It is hard to tell the living from the dead.

Don Pedro refuses to see his own swollen eyes and his lips like dry figs, but within his miserable, rich hut he is hounded by the ghost of those faces without torsos, creeping on the mocking luxury of the Guadix furniture, adhering to the large tapestry with the emblems of the Order of Santiago; they appear on the tables, close to the useless Erasmus and Virgil, among the disarrayed dishes that reveal, in their foodless gloss, the heraldic Ave Maria of the founder.

The sick man writhes as if possessed. His right hand, with the wooden rosary coiled around, grips the bed’s tassels. He tugs angrily, as if to drag the damask canopy and bury himself under its embroidered allegories. But even there the troop’s groaning would have reached him. Even there would have slid the spectral voice of Osorio, whom he had assassinated at the beach of Janeiro, and so the voice of his brother don Diego, murdered by the Querandí on the day of Corpus Christi, and the other voices, more distant, of those he led during the sack of Rome, when the Pope and his cardinals had to take refuge in the castle of Sant Angelo. And had that dreadful wail of tongueless mouths not reached him, he would never have evaded the persecution of rotten flesh, whose stink invades the room and is stronger than that of medicines. Oh!, there is no need to lean out of the window to remember that outside, at the very centre of the camp, are the oscillating corpses of the three Spaniards he had hanged for stealing and eating a horse. He imagines them, dismembered, for he knows that other companions have devoured their thighs.

When will Ayolas return, Virgin of Buen Aire? When will those who went to Brazil for supplies return? When will this martyrdom come to an end and when will they set off for the land of metals and pearls? He bites his lips, but they release the frightening roar. And his blurred vision returns to the plates painted with the Marquess of Santillana’s coat of arms, resembling in his delirium a red and green fruit.

Baitos, the crossbowman, also imagines. Curled up in a corner of his tent, on the hard soil, he thinks that the Adelantado and his captains are indulging in marvellous feasts, while he perishes with his entrails scratched by hunger. His hatred towards the chiefs becomes more and more frenzied. That anger nurtures him, feeds him, prevents him from lying down to die. Nothing justifies such hatred, but in his life devoid of fervour it acts as a violent incentive. In Morón de la Frontera he detested the lords. He came to America believing that gentlemen and peasant alike would become rich, that there would be no differences. How wrong was he! No armada sent by Spain to the Indies had been as noble as that which anchored at the River Plate. Everyone put on airs of a duke. On the bridges and within the chambers they conversed as if in a palace. Baitos has spied on them with his small eyes, squinting under his bushy eyebrows. He had some esteem for only one of them, who would sometimes approach the commoner soldiers, and that was Juan Osorio; his fate is well-known: he was assassinated in Janeiro. The lords had him killed out of fear and envy. Oh, he hates them so, so much, with their ceremony and their airs and graces! As if all were not born the same way! And even more angry is he when they affect a sweeter tone, speaking to the sailors as equals. Lie, lies! He is tempted to rejoice after the foundation’s disaster, which has dealt such a harsh blow to those false princes’ ambitions. Yes! And why not rejoice?

Hunger clouds his mind and makes him delirious. Now he blames the chiefs for the situation. Hunger! Hunger! Oh! To bite into a piece of meat! But there is not… There is not… Just today, with his brother Francisco, holding up each other, he searched the camp. There is nothing left to steal. His brother has offered to no avail, in exchange for an armadillo, for a snake, for some leather, for a bite, the only jewel he possesses: that silver ring with a wrought cross his mother gave him before setting sail from San Lúcar. But even if he had offered a mountain of gold, it would have been in vain, for there is not, there is not. There is nothing left but tighten their pain-punctured stomach and double up and shiver in a corner of the tent.

The wind spreads the stench of the hanged. Baitos opens his eyes and licks his deformed lips. The hanged! Tonight is his brother’s turn to stand guard by the gallows. He must be there now, with the crossbow. Why not crawl towards him? Together they could take one of the bodies down and then…

He takes his wide hunting knife and comes out staggering.

It is a freezing June night. The wan moon turns pale the huts, the tents and the scarce fires. It would seem that for a few hours there will be peace with the Indians, themselves also starving, since the attack has waned. Baitos gropes blindly among the bushes, towards the gallows. It must be this way. Yes, there, there they are, like three grotesque pendula, the three mutilated corpses. They hang, armless, legless… A few more steps and he shall reach them. His brother must be nearby. A few more steps…

But suddenly, four shadows arise out of the night. They approach one of the bonfires and the crossbowman feels his anger revive, poked by the untimely presences. Now he sees them. They are four lords, four chiefs: the teenager don Francisco de Mendoza, former steward to don Fernando, King of the Romans; the very young don Diego Barba, knight of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem; Carlos Dubrin, milk-brother of our lord Charles V; and Bernardo Centurión, the Genoese, former captain of four of prince Andrea Doria’s galleys.

Baitos hides behind a barrel. He is irritated to see that not even now, when everyone is assailed by death, have they lost any of their presence and their pride. At least he believes so. And holding on to the barrel to avoid falling, for he is almost depleted of strength, he confirms that the knight of Saint John still flaunts his red coat of arms, with the white, eight-pointed cross open like a flower on the left side, and that the Italian wears over his armour the huge otter-fur cloak that makes him so vain.

This Bernardo Centurión he execrates more than anyone else. Already in San Lúcar de Barrameda, upon setting sail, he stored up against him an aversion which has grown throughout the voyage. The soldiers’ tales about him fomented his animosity. He knows he has been the captain of four of Prince Doria’s galleys and that he has fought under his command at Naples and Greece. The Turkish slaves roared under his whip, chained to the oars. He also knows that the great admiral himself gave him that fur cloak the same day the Emperor granted him the grace of the Fleece. So what? Does that justify so much conceit, by chance? Anyone looking at him, while onboard the ship, could have thought it was Andrea Doria himself coming to America. He has a way of turning his swarthy, almost African head, making the gold earrings flash over the fur collar, that drives Baitos to clench his teeth and fists. Captain, captain of Prince Andrea Doria’s armada! So what? Is he less of a man, by any chance? He also counts two arms and two legs and everything necessary…

The lords chat by the light of the bonfire. Shiny are their palms and their rings when they move with the sobriety of courtesan gesture; shiny is the cross of Malta; shiny is the lace of the King of the Romans’ steward, over the tattered doublet; and the otter cloak opens, lavishly, when its owner places his hands on his hips. The Genoese turns his curly head with arrogance and his round earrings shake. Behind, the three corpses revolve between the wind’s fingers.

Hunger and hatred choke the crossbowman. He desires to shout but fails, and he falls in a faint, silently, on the short grass.

When he regained consciousness, the moon had hidden and the fire barely blinked, soon to extinguishing. The wind had become silent and instead there was the distant sound of the howling Indians. He stood up heavily and looked towards the gallows. He could hardly make out the executed. He saw everything as if covered in a thin fog. Someone moved, close by. He held his breath, and the captain of Doria’s otter cloak stood out, magnificent, by the red light of the embers. The others were no longer there. No one: not the King’s steward, not Carlos Dubrin, not the knight of Saint John. No one. He surveyed in the darkness. No one: not his brother, not even the lord don Rodrigo de Cepeda, who usually did his round at that hour, with his prayer book.

Bernardo Centurión stands between him and the corpses: only Bernardo Centurión, for the sentinels are far from there. And a few metres away, the maimed bodies, swinging. Hunger so tortures him that he knows he shall become mad if he does not mollify it soon. He bites his own arm until he feels, on his tongue, the warmth of blood. He would devour himself if he could. He would cut off that arm. And the three livid bodies hang, with their awful temptation… If only the Genoese went away for good… For good… And why not, truly, in the most terribly true sense, for good? Why not seize the occasion before him and eliminate him forever? No one will ever know. A single leap and the hunting knife will be buried in the Italian’s back. But can he, thus exhausted, jump so? In Morón de la Frontera he would have been sure of his adroitness, of his agility…

No, it was not a leap; it was the surge of a cornered hunter. He had to lift the hilt with both hands to stick the blade. And how it disappeared into the smoothness of the otters! How it became lost, on its way to the heart, into the flesh of that animal he is hunting and has reached at last! The beast falls with a muffled growl, shaken with convulsions, and he falls over and feels on his face, on his forehead, on his nose, on his cheeks, the caress of its skin. Twice, thrice he pulls out the knife. In his delirium he ignores whether he has killed the Prince of Doria’s captain or one of the tigers that prowl around the encampment. Until the death rattles cease. He searches under the cloak and stumbles upon the arm of the man he has just stabbed; he severs it with his knife and sinks in his hunger-sharpened teeth. He thinks not about the horror of what he is doing, but only about biting and sating. Only then does the embers’ crimson brushstroke reveal, further away, much further away, knocked down by the palisade, the Italian corsair. He has an arrow stuck between his glassy eyes. Baitos’s teeth come across his mother’s silver ring, the ring with a wrought cross, and he sees his brother’s crooked face, among those furs which Francisco took from the captain after his death, to wrap himself up.

The crossbowman screams inhumanly. Like a drunk man, he climbs the coral and willow trunk stockade and starts running downhill, towards the Indians’ bonfires. His eyes pop out of their sockets, as if his brother’s torn hand clasped his throat tighter and tighter.

“Buenas Aeres”, illustration from Ulrich Schmidl’s Vera Historia

III

The Mermaid

1541

Travelling through the great rivers, from the palisades of Buenos Aires to the fortress of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, there come the news about the white men, about their victories and despairs, their mad journeys and the treacherous passion with which they kill each other. The news are carried by the Indians in their canoes and pass from tribe to tribe, penetrating deep into the forests, scattering through the plains, becoming disfigured, confused, billowed. They are brought by ferocious or curious creatures: jaguars, pumas, vizcachas, armadillos, bespattered serpents, monkeys, parrots, and infinite hummingbirds. And they are also transmitted in the whirl of opposing winds: the South-eastern, blowing with the smell of water; the dusty Pampero; the Northern, pushing clouds of locusts; the Southern, its mouth rough with frost.

The Siren heard of them years ago, when the expeditions of Juan Díaz de Solís and Sebastián Caboto first appeared amazing the riverscape. She left her refuge in the lake of Itapuá just to see them. All of them she has seen, as she later saw those who came aboard the magnificent fleet of Don Pedro de Mendoza, the founder. And she has become anxious. Her companions questioned her, mockingly:

“Have you found? Have you found?”

And the Siren merely shook her head, sadly.

No, she had not found. So she told the Anta, with its mule ears and calf snout, who nurtures in its womb the mysterious bezoar stone; so she told the Carbuncle, who flaunts an ember on the forehead; so she told the Giant, who lives near the rumbling falls and fishes in the Peña Pobre, naked. She had not found. She had not found.

She never returned to the lake of Itapuá. As she swam idly, half-hidden by the fringes of the willows, the birds silenced their bustle to listen to her sing.

She traverses the patriarchal rivers from end to end, fearing neither the whirls nor the waterfalls that raise curtains of transparent rain; neither the winter’s harshness nor the summer’s flame. The water toys with her breasts and her hair; with her agile arms; with the blue-scaled tail, extended in thin, rainbow-coloured caudal fins. Sometimes she stays submerged for hours and sometimes she lies on the tranquil current, and a sun-ray reposes on the freshness of her torso. The yacares keep her company for a stretch; the ducks and the pigeons known as apicazú flutter around her, but soon they grow weary, and the Siren continues her journey, downstream, upstream, arched like a swan, her arms loose like braids, reminiscent of certain Renaissance jewels, with baroque pearls, enamels and rubies.

“Have you found? Have you found?”

The scorn: Have you found?

She sighs, feeling she shall never find. White men are like the natives: mere men. Their skin is finer and fairer, but they are that: mere men. And she cannot love a man. She cannot love a man who is merely man, nor a fish that is merely fish.

Now she swims along the River Plate, towards Mendoza’s village. The Giant has referred that some brigantines descended from Asunción, and the pheasants told her that their chiefs are ready to depopulate Buenos Aires. Precarious was life in the city. And sad. Only five years have passed since the Adelantado built the huts there. And it will be destroyed.

In the vagueness of twilight, the Siren discerns the three ships nodding in the Riachuelo. Further on, in the plateau, the fires blaze in the death-fated village.

She approaches cautiously. There is almost no one left on the brigantines. That allows her to come near. Never as today has she rubbed the bows with her delicate breast; never has she seen so close the square rigs that tremble with the passing breeze.

Those are old, badly caulked ships. The June night collapses over them. And the Siren gives silent strokes around the hulls. On the biggest one, high up on the stem, under the bowsprit, she notices an armed figure, and she immediately hides, fearing detection. Then she reappears, her dark hair wet, her dark lashes dripping.

Is it a man? Is it a man wielding a knife? Or no… Or is it not a man… Her heart leaps. She dives in again. Everything is covered by the night. Only the cold stars shine bright in the sky; and in the village, the fires of those preparing the journey. They have burnt the ship turned fortress, the chapel, the houses. Some men and women weep and refuse to embark, while the cows utter sonorous, desperate moos, sounding like melancholy horns in the desolate darkness.

At dawn, the brigantines are still being loaded. They are to depart today. In what used to be Buenos Aires, only a letter remains, with instructions for whosoever arrives at the port, advising on how to guard against the Indians and promising Paradise in Asunción, where Christians have seven hundred slave women to serve them.

The ships sail up the river, among the islands of the delta. The Siren follows them from a distance, balancing on the swing of the foamy wakes.

Is it a man? Is it a man wielding a knife?

She had to wait for the afternoon’s indecisive light to see him. He had not abandoned his lookout post. With a trident in his right and a buckler in his arm, he guarded the bowsprit, tugged by the foresails with the slightest rocking. No, he was not a man. He was a being like her, of her own ambiguous caste, only half his body a man; for the rest of it, from waist to feet, was transformed into a corbel attached to the ship. A stiff, triangular beard divided his breast. A small crown surrounded his forehead. And so, half-man, half-capital, entirely dark, tanned, grooved by the storms, he seemed to drag the ship by the impulse of his robust torso.

The Siren gasped. The soldiers’ heads emerged on the board. And she hid. She dived in so deep that her hands became entangled in strange, colourless plants, and the waves filled with bubbles.

The night sets up again its gloomy tents, and the daughter of the Sea risks approaching the prow and sliding up to the bowsprit, avoiding the yellow stains of the lit lanterns. In their brightness, the Figurehead is even more beautiful. Light climbs his Ocean god’s beard, up to his eyes gazing into the horizon.

The Siren calls him in a whisper. She calls him, and so soft is her voice that the nocturnal animals, roaring and laughing in the nearby thickets, become quiet at once.

But the Figurehead with the sharp trident answers not, and there is no sound but the water splashing against the brigantine’s sides and the psalmody of the page, announcing the hour by the hourglass.

Now the Siren sings to seduce the impassive one, and the boards of the three ships become populated with marvelled heads. Even Domingo Martínez de Irala, the violent chief, bursts in the bridge. And they all imagine a bird singing in the verdant grove and survey the trees’ darkness. The Siren sings and the men remember their Spanish villages, the familiar rivers murmuring in the gardens, the country houses, the erect stone towers before the flight of the swallows. And they remember their distant loves, their far-off youths, the women they caressed under the shade of wide oaks, to the sound of tabors and flutes and of bees making the fields drowsy with their buzz. They smell the fragrance of hay and wine mixing with the hum of fast distaves. It is as if a waft of air from Castile, from Andalusia, from Extremadura, rocked the sails and the King’s banners.

The Figurehead is the only one unaffected by that outlandish voice.

And the men go away, one by one, when the song ceases. They plunge into their beds or into the rope reels, and dream. One would say that the three brigantines have suddenly blossomed, that there are garlands hanging from the sails, with so many dreams.

The Siren stretches in the quiet water. Slowly, anxiously, she ties herself to the old prow. Her tail beats against the worn-out boards. With nails and fins, she begins ascending towards the Figurehead, who points from above to treasure-filled ways. Now she girdles the broken corbel. Now she embraces the wooden waist. Now she presses her desperation against the insensitive trunk.

She kisses the carved lips, the painted eyes.

She hugs him, she hugs him, and down her cheeks roll the tears she could never cry. She feels a pain so sweet and terrible, for the short trident has pierced her breast and her pale blood flows from the wound, over the Figurehead’s slender body.

Then, a plaintive cry is heard and the statue snaps off the bowsprit. They fall into the river, embraced in a single form, and they sink, inseparable, among the silvery escape of silversides, of prochilods, of sorubims.

A Mermaid, John William Waterhouse

VI

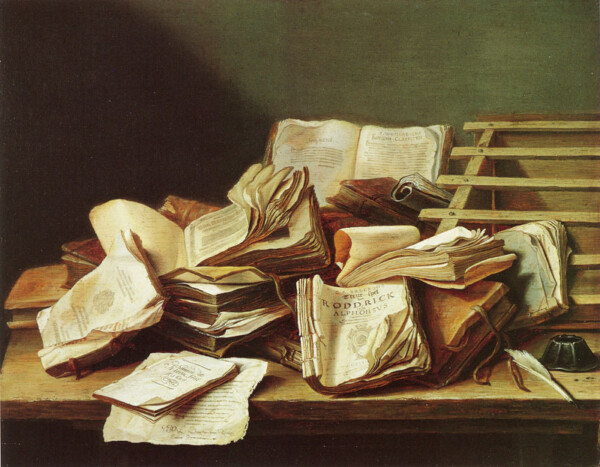

The Book

1605

“A pair of black velvet slippers!”

The pulpero raises them, like two large beetles, for the sun to highlight their luxury.

Under the eave, the four players look towards him. The notary keeps the card raised and exclaims:

“If I win, I shall buy them.”

And the pulpero’s daughter, in her affected voice:

“They are worthy of the Mister’s foot.”

The latter winks at her and the game proceeds, after the Flemish acting as banker calls them to order.

“Twelve yards of Netherlandish cloth! Two adorned bedspreads, with their fringes!”

Under the vine’s shade, Lope enters what is dictated, drawing his beautiful rounded script.

They are in the rammed earth courtyard. On one side, around a table sheltered by the eave, four men –the Flemish miller, the notary, a Dominican friar and a soldier– try their luck at lansquenet, the game invented in Germany during the times of Charles V or even before, when his grandfather Maximilian of Habsburg reigned; the game the troops took from one end of the imperial dominions to the other. Nearer, close to the vine, the pulpero’s daughter has sat on a chair, between two large jars. She would be pretty if she removed the layer of vermillion and ceruse with which she hopes to enhance her charm. Below so much cheap makeup, her wet eyes sparkle. She wears a very wide skirt, a farthingale, and she smoothes its plaits with her black-edged nails. The coloured glasses of a costume jewel shake on her chest, under the ruff. Sweating, with rolled sleeves, her father bustles about in the courtyard. A Negro helps him unnail and draw goods from some barrels and boxes, stealthily unloaded the night before. Those are smuggled packages from Porto Bello, on the other extreme of America, sent by Pedro Gonzalez Refolio, a Sevillian. Buenos Aires smuggles from the governor down, since it is the only way for commerce to survive, and so the grocer’s tone is barely demure as he dictates:

“Arquebuses! Seven arquebuses!”

The soldier turns towards him. His eyes leap at the sight of the matchlock guns and the hooks. The banker complains:

“Let us play, gentlemen!”

And he shuffles the cards, whose ace of golds boasts the shield of Castile and León and the double-headed eagle.

“A fine, three-broadloom carpet! Four sheets from Ruán!”

Lope keeps writing down on his notebook. Neither the pulpero nor his daughter can write, so the lad is in charge of accounting and copying. It bores him to death. The girl notices that; she leaves the packages for a while and approaches him with myriad flirtatious contrivances. She pours a glass of wine for him:

“For the writer.”

The writer sighs and drinks it in a gulp. Writer! He would certainly like to be that, not a wretched scribe. The girl devours him with her eyes. She leans to pick the glass and murmurs:

“Will you come tonight?”

The teenager has no time to answer, for the pulpero is now saying:

“It is over. One… Two… Three… Five yards of white satin for chasubles…”

He has unfolded them as he measured them, and now he emerges, sweatier and uglier than ever, from so much fragile purity overflowing the barrels.

“Huh, what is this?”

With his right hand he lifts a book that lay hidden deep inside the box. The merchant is startled:

“How the hell did this get here with the merchandise?”

He opens it clumsily, and since the letters mean nothing to him, he hurls it at the players. The notary catches it in mid-air. Holding the cards with one hand, he skims through with the other.

“This work has been published this year. Look, your Mercies: Madrid, 1605.”

The banker, beset by mosquitoes, loses his patience:

“What are we doing here? Reading or playing?”

On his left, he makes the Dominican cut the deck.

The friar takes the book in turn –it does not contain much: barely more than three hundred pages–, and declares, doctoral:

“Perhaps it is a dangerous traveller and we should submit it to the Holy Office.”

“None of that,” argues the pulperia owner. “They would start inquiring upon how it reached my hands.”

And the soldier: “It can be nothing bad, for it is dedicated to the Duke of Béjar.”

The notary cleans his glasses and puffs:

“For me, there is no duke but the Duke of Lerma.”

And so they all start arguing. Naming the favourite was enough to disturb the calm in the courtyard, as if a hundred wasps had broken in. For a moment, the characters lower their tone and glimpse around: the annoyed pulpero has said that lord Phillip III is the Duke’s slave and that that lofty man rules Spain at will. Above the different voices, the miller raises his own:

“Shall we play? Shall we play, then?”

From her hard chair, the girl claps and takes advantage of the confusion to settle a fiery gaze on Lope.

“Peace, gentlemen!” begs the Dominican. “I have been reading the beginning of this book and it deserves no fuss, I believe. It is a book of mockery.”

The notary shakes his head:

“What shall be of us with such foolish things as are now published? Just give me something like those books we used to read and delight in when we were boys. Las Sergas de Esplandián…”

“Lisuarte de Grecia…”

“Palmerín de Oliva…”

The players have become silent, for the sudden remembrance has brought them back to their youth and to the novels that made them dream, back in far-off Spain, in the quietness of the distant hamlets, in the provincial lodgings where, by candlelight, fantastic warriors appeared with a lady on the rump of their horses, delivering marvellous speeches to the clash of gold weapons.

Only the miller from Flanders, who has never read anything, insists with his complaint:

“If we are not playing, I am leaving.”

The rest calm down.

“We should give it to Lope,” concludes the notary. “Nothing new could appeal to us now, for we have been educated in the office of fine literature. Gentlemen, our race is becoming lost. The age of stupidity and leniency begins. Oh, don Duardos of Brittany, don Clarisel, don Lisuarte!”

The pulpero roars with a thick laughter and aligns the arquebuses under the vine.

“Another round of Guadalcanal wine!” And the book, almost unbound after so much tugging, flutters once again through the air, towards the meditative boy sharpening his quill.

Now the house is asleep, dark with shadows, white with infinite stars. The girl, tired of waiting for her listless lover, traverses the courtyard in tiptoe, towards his room. She peeps through the door and sees him, lying face down on the bed. By the light of a candle, he is reading the book, the damned book with butter-coloured covers. He laughs, engrossed, a thousand leagues from Buenos Aires, from the grocer, from the smell of fruit and garlic that overflows the house.

The pulpero’s daughter and her pride cannot stand it. She storms in and reproaches him in a low voice, in a hectic whisper, fearing her father might hear:

“You bastard! Why haven’t you come?”

Lope wants to reply, but he dares not raise his voice either. Then, a stifled dialogue ensues, between the girl whose flush strives to appear from below the vermillion mask, and the lad who defends himself with the volume, as if chasing flies away.

At last, she snatches the book from his hands so fiercely that he is left holding the parchment covers. And she flees, pressing it against her chest, furious, towards her room.

There, before the mirror, the familiar presence of vulgar jewels, ointment pots, and horn and shell combs soothes her, but does nothing to lower the fever of her disappointment. She begins to comb her fair hair. The book is left abandoned amid the vases. She speaks alone, grimacing, appraising the grace of her dimples, of her profile. She reproaches the absent lover for his indifference, his coldness. Her green eyes, clouded by tears, come to rest over the abandoned book, reviving her fury. She turns the pages, anxious. Some lines in the first pages do not cover the whole folio. She ignores that those are verses. She wishes she knew what they say, what those mysterious, inimical letters mean, their seduction so attractive and stronger than those charms only enjoyed by the impassive mirror.

And so, with deliberate slowness, she tears pages at random, she twists them, she bends them in ringlets and ties them into her own golden locks. She lies down, her hair transformed into a caricaturesque Medusa, among whose absurd curls appear, here and there, the torn fragments of Don Quixote de La Mancha. And she cries.

Books and Pamphlets, Jan Davidszoon de Heem

VIII

Miracle

1610

The brother porter opens his eyes, but this time it is not the brightness of dawn which, sliding into his cell, puts an end to his short sleep. There is still an hour left until sunrise and in the window the stars have not paled yet. The old man stirs on the hard bed, restless. He pricks up his ears and notices that he has been woken up not by light, but by some music coming from the convent’s gallery. The brother rubs his eyes and reaches the door in his room. Everything is silent, as if Buenos Aires were a city buried in sand for centuries. There is nothing alive but that singular, most sweet music, undulating within the Franciscan convent of the Eleven Thousand Virgins.

The porter recognises it, or at least believes he does, yet at once understands himself to be mistaken. No, it cannot be Father Francisco Solano’s violin. Father Solano is now in Lima, more than seven hundred leagues away from the River Plate. And yet…! The brother made the journey from Spain along with him, twenty years ago, and has not forgotten the sound of that violin. Music by angels it seemed, when the holy man sat on the prow and caressed the strings with the bow. Some seamen assured that the fishes lifted their jaws and fins, to better listen to him, from within the ship’s foam. And one of them told that one night he had seen a siren, a true siren with a scaled tail and black lichen hair, who escorted the fleet for a long time, balancing on the waves to the violin’s rhythm.

But this music must be something else, because Father Francisco Solano is in Perú, and coming down from Perú to Buenos Aires, aboard the slow wagons, takes a lot of time. And yet, and yet…! Who plays the violin like that in this city? No one. No one knows, like Solano, how to produce the notes that make one sigh and smile, enrapturing the soul. The Indians in Tucumán laid down their arrows, clasped their hands together and came to his miraculous call. And the rainforest jaguars too, like those tigers in ancient paintings, yoked with garlands to triumphal chariots. The brother porter has been witness to such prodigies in San Miguel del Tucumán and in La Rioja, where the orange tree planted by the miracle-worker blossoms.

It is an ineffable music, most simple, most easy, which however brings to mind the celestial instruments and the choirs lined up around the divine Throne. It travels around the cloister in Buenos Aires, air-like, as a harmonious breeze, and the brother porter follows it with a beating heart.

In the courtyard where Fray Luis de Bolaños’s cypress stands, the enchanting spectacle stops the lay brother, who crosses himself. It is well into July, but the air becomes embalmed with spring-like fragrance and warmth. The entire tree is laden with immobile, attentive birds. The porter discerns the kiskadee’s yellow and the meadowlark’s red breasts, and the thrush’s mourning and the mockingbird’s grey feathers, and the cardinal’s crest and the flycatcher’s long tail. The convent of the Eleven Thousand Virgins has never seen so many birds. The lapwings are perched on a scaffolding, right where the works ordered by Fray Martín Ignacio de Loyola, bishop of Paraguay and nephew of the saint, have ensued. And there are horneros and woodpeckers in the scaffolding, and plovers and scarlet flycatchers and robins and hummingbirds and even a solemn owl. They are listening to the invisible violin, their round eyes crackling, their wings still. The cypress resembles an enchanted tree that gives birds as fruit.

The music swings round the gallery, and further on the brother comes across the convent’s cat and dog. Moving neither tail nor ear, like two Egyptian statues, they stand guard before Fray Luis de Bolaños’s cell. Between them, a hanging spider has quit working on its web to listen to that unique melody. And the brother porter observes that the little beasts that roam the cloister’s solitude at that hour are also standing, fascinated, like detained in their march by a higher order. There are little mousses, doctoral toads, a lizard, insects with brown and green carapaces, luminous worms and, in a corner, as if embalmed for a museum, a country vizcacha. Nothing moves, not an elytron, not an antenna, not a whisker. They are barely known to be alive by the slight tremor of their maws, by a quick wink.

The brother porter pinches himself to ascertain whether he is dreaming. But no, he is not dreaming. And the chords keep coming from Fray Luis’s cell.

The lay brother pushes the door and is stunned by a new marvel. A strange clamour overflows the bare chamber. In the middle, the esparto mat that serves as the Franciscan’s bed is silhouetted against the earthen floor. Fray Luis de Bolaños is in prayer, enraptured, and the marvel is that he is not touching the floor but floating several inches above it. His chaguar lace hangs in the air. Thus have the Indians seen him on other occasions, in his reductions of Itatí, of Baradero, of Caazapá, of Yaguarón. Around him, like a musical halo, the sounds of the violin itself coil their ring.

The brother porter falls on his knees, his forehead deep between his palms. All of a sudden, the hidden concert ceases. The brother raises his eyes and sees Fray Luis standing by his side, telling him:

“The holy Father Francisco Solano has died today in the Convent of Jesus, in Lima. Let us pray for him.”

“Pater Noster…” whispers the lay brother.

The cold of July comes in now through the cell’s window. When the violin becomes quiet, the silence that lulled Buenos Aires is broken by the clamour of wagons thundering the street, by the tolling bells, by the clicking heels of muffled-up women devoutly attending the first mass, by the voices of the slaves sluicing the courtyard in the neighbouring house. The birds have taken flight. They are not returning to Fray Luis’s cypress until spring.

Leave A Comment