María Carman

Tensiones entre vidas animales

y humanas (2020)

Vínculo al texto original:

Este artículo se publicó originalmente en la Revista Nueva Sociedad (NUSO) N.° 288, julio-agosto 2020, y se puede leer además en la versión en línea (ver el vínculo al texto original). Les debo mi agradecimiento tanto a los editores de la revista como a la autora, María Carman, por permitirme traducir y publicar este escrito. Además, la ilustración que figura como portada también se publicó originalmente junto con este texto en la misma revista, y es obra de una queridísima amiga mía, Ana Lignelli, quien me permitió usarla en el blog. Vale recomendar aquí también su página personal: flickr.com/photos/der_baum.

La autora de este artículo, María Carman, es antropóloga y novelista. Es investigadora principal del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet) de Argentina y profesora de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA). Coordina el equipo «Antropología, ciudad y naturaleza» del Área de Estudios Urbanos del Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani (UBA). Para conocer más sobre su obra, recomiendo visitar su perfil en Academia.edu (uba.academia.edu/MaríaCarman). Le agradezco una vez más por dar su apoyo a esta traducción.

Tensions between animal and human lives

The prevailing rhetoric among the movements against the use of animal-drawn vehicles oscillates between an exaltation of the horse, the zeal for his health and freedom, and the condemnation of the purported aggressors: the cartoneros, or cardboard scavengers, who use them to work. Contrasting these dissimilar attributions of dignity makes for an explanation not only of hegemonic classification systems, but also of how the borders and moralities of humanness and animalness are defined in different conflicts within our societies.

Introduction

In this article, I address the modes of identification and relation devised by some conservationist movements in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, in Argentina, particularly those seeking to forbid the use of horses by scavengers of recyclable products, known as cartoneros1. Which groups endowed with which attributes are included in a moral community and which are left out? Which are the processes of production, promotion and reception for the dominant representations of a human “close to beastliness” —whose actions are meant to be corrected— and an animal close to humanness, whose very being would merit remedy and protection?

The prevailing rhetoric in pro-horse movements oscillates between an exaltation of the horse, the zeal for his health and freedom, and the purported aggressors’ condemnation. While the horse’s agency is increasingly vindicated, the carter’s2 is only highlighted in terms of aggression or exploitation. If the horses’ personality is profiled as an aggregate of positive attributes, the cardboard scavengers’ nature is likewise deserving of an emphatic negative characterisation, generating a set of opposites.

My purpose in contrasting these dissimilar attributions of dignity is to explain not only how hegemonic classification systems work, but also how the borders and moralities of humanness and animalness are defined in different conflicts within our societies.

The horse advocates determine a hierarchical system for animals and humans as worthy of moral attention or not. By establishing a caring and healing bond with the horses, their relationship with the rest of the human community is basically divided into two attitudes: proselytism —towards those who can be converted—, or else, condemnation for those who are deemed as exploitative and, as per such classification, irredeemable.

María Carman

Restoring the horse’s dignity

Increasingly and in different regions of the Western world, conservationist organisations seek to restore a fuller life for those animal species abused by humans. In their opinion, animals shall be redeemed in their subjectivity not only when their singularity, agency or dignity becomes recognised, but also once their rights are safeguarded.

The advocates of the animal person3 draw upon antispeciesist slogans disputing the superiority of the Homo sapiens species and demand that every animal be given the same treatment as humans. Those who support these ethics without species —or interspecies ethics— emphasise that physical differences between humans and animals should not be a reason to discriminate upon the treatment of non-human animals, given the significant similarities as regards the capability to feel pain, pleasure and other kinds of emotions. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian doctrine, Peter Singer has been one of the foremost proponents of this doctrine, ever since the publishing of his influential book, Animal Liberation, in the 1970s. One of the antispeciesist tenets bears on extending the basic principle of equality among humans to sentient animals. Such equality, argues Singer, depends not on intelligence, physical strength or other features, but is a moral idea4.

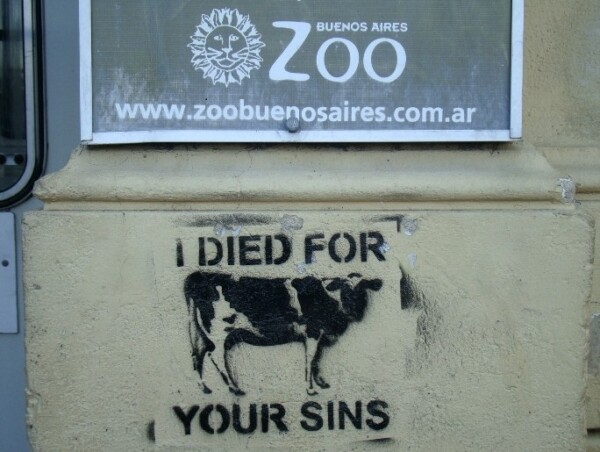

The activities undertaken by conservationist movements in Argentine cities are linked to denunciation campaigns or demonstrations against keeping species in captivity, abusing, neglecting or killing domestic animals, and scientific experimentation on any kind of animal. For instance, some vegan groups painted graffities on the walls of Buenos Aires’s Zoo when it was still open, calling on to release the animals held in captivity there and promoting a meat-free diet as a lifestyle. Other activists take action upon the suffering of an emblematic animal, such as the polar bear in the zoo of Mendoza or the orangutan Sandra in the old zoo of Buenos Aires, declared a non-human subject of law in a 2014 court decision5.

In this context, empathy towards horses is ever-increasing and finds new means of expression, both within animal protection organisations and among other people with no specific affiliation. Activists do not only make demonstrations against horse abuse during traditional festivities in the country’s inner provinces —horse taming festivals, rodeos, gaucho parades—, but also against their labour exploitation in urban contexts. The movements against animal-drawn vehicles, proliferating in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires and other regions of the country, struggle for cardboard scavengers to cease using horses in their work activities.

These groups seek to transform a relationship of allegedly undue appropriation —the horse’s exploitation by the carter— into a relationship of protection: if they get to recover that animal, then they will be able to heal it, to give it a new life. Along with veterinary doctors, lawyers and other professionals, these movements train independent rescuers to identify horses abused by carters. They use different means —talks, pamphlets and social media— to communicate the necessary steps to seize an injured horse: filing a complaint, pursuing the carter and informing the police on its location; summoning a veterinary doctor to certify the injuries; taking photographs for the criminal complaint to succeed; contacting an NGO not only to assist the abused horse, but also to take over the lawsuit and provide evidence. Particular emphasis is placed on the fact that the rescuer must not try to be a hero and attempt to take the horse away from the carters, since the latter are usually violent. In consonance with this appraisal, the rescuers tend to express their fear of being attacked by the carters: “I place myself beside the horse to see if it’s alright —one of them tells me—. Someday I’ll get lashed or they’ll try to run me over with the cart”.

During an awareness talk, a lawyer pictured the cardboard scavengers as people who “try to take a loaf of bread home and are not fit to ride a horse”. Using terms identical to the vocabulary used for human adoptions, the speakers at these talks or at the NGO web pages comment on the happy path of Zamba, Marito or Luján: horses rescued thanks to these complaints, which are now under custody, live a family life or have secured new ownerships.

According to estimates by the NGO Basta de Tracción a Sangre, some 70,000 horses and 1,500,000 people are linked, directly or indirectly, to garbage collection in Argentine urban zones6. The “Basta de TAS” campaign, led by the homonymous NGO, proposes to restore dignity to animals as well as scavengers by replacing the former with motor vehicles or electric bicycles and establishing a horse sanctuary to place them up for adoption. The pioneering case in horses replaced by motor vehicles took place in the Cordobese city of Río Cuarto, where this NGO worked together with the municipality.

In contrast with the apparent abuse by the carters, the horse sanctuary proposal is set out as an altruistic and selfless action: the horses are not forced to yield anything in return for their freedom. In the Edenic nature of a sanctuary, the horse is to recover its wild spirit; herein lies the moral imaginary of many animalist groups.

The wild horse also constitutes an archetype of freedom in our societies7. The horse in the sanctuary may never become fully wild, but at least it shall be free from the slavery of the cart. The institutional video of the Proyecto Caballos Libres [Free Horses Project] displays precisely this passage from exploitation to freedom. The harsh term chosen to depict the working use of the horse seems to connote not so much an individual or familial survival strategy as a large-scale capitalistic practice. From the conservationist perspective, the horse is not in the world to be abused, for it has a certain autonomy that must be respected. The ideal is that the animal may find in sanctuaries, or else in refuges, a place to flourish, to develop its true being8.

The hour of abolitionism

Movements against animal-drawn vehicles not only place different social segments under the same intersectional banner in defence of horses, but also identify a common adversary from the lower classes. Carters are seen as an obscene body within the public space: an overweight for the horse and a visual hindrance offensive to the eyes. Interviewed activists and pro-horse movements’ blogs concur in describing animal drawing as an uncivilised, inhuman and savage act that brings to mind long-past stages in the history of humanity, such as the dark Middle Ages. If these poor animals have been treated as slaves, then the hour of abolitionism has come.

An environment official from a southern municipality of the Greater Buenos Aires laughingly tells me how he perceives the activists against draught animals: “Some of them are somewhat extremist. If they could shoot him [the carter] in the public square, they would do so… Or they would strangle him. Or they would place him on an electric chair”. The typical emotional rhetoric of the authorised, anonymous advocates does not hesitate to characterise the carters in the harshest of terms. Those who ride horses as part of their work are seen as aggressors who cause suffering upon the person they defend: the horse.

Carters embody the worst conceivable combination: living off wastes and using a noble animal for a vile purpose. “They [the carters] are insensitive, for them it [the horse] is disposable: it is just something which moves their products from one place to another”9. These people’s interiority is never discussed, as if it were structurally deficient or only expressed in the acts of sacrificing or subduing other living beings. I quote another fragment from that interview to illustrate this point: “Now you see, a new subspecies has arisen: people with no culture, no sensitivity”.

Notice the paradox between proclaiming an ethic common to all species —a characteristic of animalism— and alluding to the poor as a subspecies, as if there were a capricious side in their human condition10: one is sometimes human, sometimes a beast. This group’s ontological status would thus become —in Judith Butler’s words— compromised and suspended11. Such degraded humanity contributes to stressing the “undesirables’” apparently unpredictable and dangerous nature.

I feel such anger, such despair… I feel disappointed by the state. No abuser serves time in prison: it’s not a serious offence. (…) We call the police [to seize the carters’ horses], but they don’t assist us. (…) Sometimes I feel like killing everyone. I‘m here to demand more severe punishments, to have the abusers go to prison.

The horse is dignity, as a symbol. And that’s what we must restore in society, such dignity12.

They act surreptitiously, like cockroaches. (…) But being poor doesn’t give you the right to be cruel. They were punished and will be cruel not only towards the poor angel [the horse], but also towards their wives, their children. They won’t stop. (…) Buenos Aires is filthy13.

It’s been proved —there’s an FBI investigation— that those who are violent towards animals are also violent towards women and children14.

Television reporter: (…) With the animal abuser, there is a brain which is no longer functioning. It is wrong.

A: Yes, some of them [carters] can’t be recovered.

R: Their cognitive level no longer sets right from wrong. He is like possessed!

A: (Opening her arms) That’s something which is beyond us.

R: (…) The channel’s telephone is on fire! There are lots of outraged people calling and insulting the carters, with expletives I cannot reproduce here. (…) Those who are violent towards animals are the same with any human being. Every spiritual guide says so. And horses are our brothers! Like trees or plants! (…) Something happens when you come into contact (with the recovered horse) which is like light: you have to experience that! It is like love. We’re not mad; this is something which happened to us. This is what makes you a better person, a better neighbour.

A: Yes, adopting [a horse] changes your life, it makes you a better person. (…) That’s why we urge you to call 911; citizens should learn how to proceed with the rescue15.

The horse advocates feel no proximity with the carters’ universe of experience, and some of them even consider that animal abuse is just a first step towards other kinds of violence. Many conservationist groups affirm in their outreach web pages this alleged link between animal cruelty and cruelty towards people, with a mantle of authority provided by quoting psychiatrists or criminologists. The empathy towards animals felt by these activists is not often translated into an equivalent measure of humanity towards those fellow humans who have been less favoured in capitalistic society’s wealth distribution; whether they are carters, homeless or other kinds of destitute people. In this context, a classical antispeciesist slogan, marking an interchangeability of positions between humans and animals (animals suffer, just like us), may be coupled with this one: I don’t care whether they [the scavengers] work themselves to death; I care about the horse. In the words of Marilyn Strathern, only that which is perceived as similar produces solidarity16.

These pro-horse groups’ peculiarities do not exhaust, of course, the wide spectrum of philosophical and political positions within animalism. Let us see an example: the same antispeciesist slogans are taken up by other groups with greater emancipatory power. Many Latin American ecofeminist groups mark a correlation between animal and human exploitation —in their terms, an intersectionality in the patterns of oppression—, as this banner summarises: Every female of every species is exploited. Against capitalism, patriarchy, speciesism and any kind of authority. Animal, human and Earth liberation.

We are not to explore here the continuities and discontinuities between different kinds of animalism; their thorough analysis would merit another work. Suffice it to note that animalist movements may either incorporate a social critique of capitalism as a hegemonic mode of production, or remain —as in the case of draught animals analysed here— perfectly immune to it. In any case, the construction of interchangeability between animals and humans —whether in its “light” version or openly contesting the neoliberal statu quo— constitutes one of the new signs of the ongoing blurring of the animality/humanity border within our Western societies.

“My only tool thing is the horse”

In contrast with the far-off sanctuaries or the refuges in which pro-horse movements seek to save the horses, the cardboard scavengers build ad hoc spaces for their horses in the vicinity of their habitat. In 2012, a popular library-stable was inaugurated in Villa La Cárcova, in the Greater Buenos Aires. On this small space, made from materials recovered by cardboard scavengers, the children gathered to read and receive educational support; meanwhile, next to them, a small horse retired from the cart rested.

In some lower-class residential complexes inaugurated in the south of the City of Buenos Aires, the inhabitants of riverside slums —now relocated— moved their horses to a place adjacent to their houses: a small garden near the playgrounds. Both the officials of the City’s Housing Institute and the very neighbours who were not cardboard scavengers judged this custom to be an undue use of communal areas within the residential complex. One neighbour, for instance, a bricklayer, considered cardboard collecting to be an especially illegitimate activity in this new complex: having left the slum, the scavengers should change their habits and improve. Other neighbours rejected the horses because of the potential health issues caused by the presence of dung and flies near the green area. Indeed, the carters felt morally rejected by their neighbours:

Ever since we moved here, everybody’s become snotty because everything bothers them. This’s a snobbish slum. We’re all from the slums! All of a sudden, nobody talks to you, they’re against scavengers. How many years did we live in the slum?17

However, after a series of meetings promoted by a team of social workers from the Housing Institute, the neighbours endorsed a project to build a stable in a nearby workroom so that carters could keep their source of livelihood. In the context of these tensions, Bernardo defined the horse as an essential instrument for his work:

I’ve had him [Coco, his horse] for two years. (…) I don’t use him much, just twice a week. (…) My only tool thing is the horse. I haven’t studied anything. I depend on this. I need to live, I need to eat. We live on cardboard. I need to depend on scavenging to support my children.

Alfonso too defends his trade, and he distances himself from those who practise it irresponsibly.

The horse is a human being who brings you the money, and you must have him well. We give him everything: parasites every three months, alfalfa, good grass. (…) I put some burnt oil on their hooves. And people look at me: “See how he has those horses!” (…) At Puente La Noria, the horses are full of holes like this. When I see them getting whipped for no reason, I say: “Hey, you thug, don’t beat that horse!” “Mind your own business, geezer”, they reply. (…) Now that it is summer, they pretty much need to wear a cap. I make a cap for my horse (…). I’m 63 [years old]: almost my entire life with cart and horses.

Carters usually distance themselves, each in its own way, from that which they are often blamed for: purported animal abuse. Some carters wear vests provided by the Government of the City of Buenos Aires, so that —in their own words— they are not discriminated against while scavenging.

Like other carters, Alfonso is illiterate and has worked his whole life collecting recyclable materials in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires. He defines the perils of using human-drawn vehicles from his own experience and that of his milieu: “The human being has nothing else than the handcart, because otherwise, what can he live off? Human beings need to eat. A handcart is human-drawing, because there is a body dragging”.

When Alfonso was asked some years ago by Housing Institute professionals about the possibility to have his horse replaced with an electric cart, he emphatically rejected the idea. Just like other carters, Alfonso describes the horse as part of his family. In the words of a veterinary doctor:

Some cardboard scavengers love their horses above anything else. They may lack diapers for their children, but never food for the horses. Fabián says: “I have no money for diapers, but here’s the bag with oats and corn”. (…) I chide him because he gives her [mare] too much food and she’s fat (…). He doesn’t use her when it’s hot, at noon, nor in winter, so that she doesn’t get soaked with dew.

(…) There’s the fanatic who takes care of it [the horse] just like a member of his family. (…) Marcelo’s mare gave birth the same day as his wife: he assisted to his mare’s delivery, not his wife’s18.

Two veterinary doctors who have filed more than 1000 clinical records on cart horses in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires concur that half of the cardboard scavengers take care of their horses, while the other half makes intensive use of their workforce at the expense of the animal’s health. The horses in the poorest condition, say the specialists, are those which are leased by neighbours. On the other hand, the conservationist groups consider that most carters abuse their horses: if the veterinary doctors heal the horses, then they are abetting the scavenger and protracting the animal’s agony. From this standpoint, animal-drawing always means exploitation. The following dialogue in the streets of La Plata illustrates different views:

Conservationist: (addressing a veterinary doctor who is healing a carter’s horse) You’re a horse murderer! (…) All you care for is the scavenger!

Veterinary doctor: But what do you think there’s running through their [the scavengers] veins and arteries?

Conservationist: (addressing the scavenger) They [the horses] can’t draw the cart. You have to do it!

Cardboard scavenger: Excuse me, ma’am, but we have blood too.

Philippe Descola summarises this kind of problems with the appropriate tact: “Many of the so-called ‘cultural’ misunderstandings —sometimes comical, sometimes tragic— are a consequence of the fact that the diverse groups populating the Earth do not truly understand the fundamental issues which impel other groups”19. We have just seen that, while conservationists seek to replace cart horses by reason of deeming them to be noble animals, carters raise the stakes by arguing that horses are part of their families. An apparently similar identification between animalists or carters and horses —summarised in considering the latter to be a relative— is coupled with different modes of relation: the former rescue the horses, the latter use them to work. In fact, a mode of identification does not define a priori a mode of relation, as Descola suggests:

Each of the ontological, cosmological and sociological formulas provided by identification are, in themselves, capable of lending support to many kinds of relation, which are not automatically derived, therefore, from the mere position held by the identified object nor from the properties assigned to it. For instance, considering an animal to be a person, and not a thing, in no way enables to prejudge on the relationship which is to develop with it, which may be associated just as much with depredation as with competition or protection20.

Conclusions

In this article, I explored an aspect of a metropolitan social group’s environmental experience: citizens who fight against urban animal-drawn vehicles. To a lesser extent, I discussed how cardboard scavengers contest these accusations and vindicate not only their work activity, but also their bond with the animal. In some cases, defining the horse as a tool is supplemented by considering the conceived animal as a friend or elder brother: animals with whom they share a bond of friendship21.

Additionally, animal protection movements take the horses’ suffering in order to come into existence as a group and give rise to protective measures realised in police reports, confiscating abused animals and creating sanctuaries or refuges. Besides, the suffering undergone by these beings makes them equal to each other. Hence, in the conservationist belief, the moral community encompasses certain sentient animals and the humans who truly understand them.

In the conflict regarding animal-drawn vehicles, this practice —deemed illegal or disruptive of the urban space— is attributed to an alleged lack of culture, or else, to straightforward bestiality, which brings to mind an evolutionist conception22 regarding less favoured groups. The capacity to symbolise or to generate culture within these subordinate sectors, placed in the lowest tiers in a scale of dignity, is permanently called into question. The animalists’ practice of seizing the carters’ horses is, in fact, inspired by an evolutionist conception. If the carters are —as some horse advocates believe— a subspecies devoid of feelings, the actions aimed at disciplining them will be a consequence of such conception of their problematic nature.

Indeed, a culture conceived as degraded would be doomed to repeating its behaviour. Suffice it to remember the belief that the carter, committing abuse on the horse, is bound by nature to make such violence extensive to his wife and children.

From an evolutionist conception, the body seems the only clear continuity which connects the “civilised” humans with those people whose humanity is underdeveloped. The accusation against “incomplete humans” does not just focus on their apparently deficient interiority, but also on their bodies: the carter is to be perceived as an obstacle for the proper functioning of urban life.

The game of mirrors also involves these dissimilar subjects’ destinies: if the urban horse is to be rescued and taken to a refuge or sanctuary, then, symmetrically speaking, the cardboard scavenger —if punishment were harsher and the laws were fairer, in terms of the activists— should be sentenced to prison. To each the shelter it is due, then, on the basis of their given dignity. According to this interpretation, horse and carter are but two sides of the same coin: victim and aggressor, innocent and guilty; a refuge for the noble being and prison for the criminal. As I have held in many ethnographies on contemporary urban life23, the evolutionist worldview is still the norm when judging and morally prescribing the popular customs and trades which are deemed to be improper, impudent or obscene.

How can we reinvent animal rights in Latin American terms, within the framework of a broader ethic of care and of beings? On the one hand, it is necessary to repoliticise the animal question and to imagine an ensemble of human rights, animal rights and nature’s rights in a cosmopolitan and emancipatory direction, moving further —as Boaventura de Sousa Santos would say— in recognising others24.

On the other hand, ecofeminist research and actions have much to teach us on how to develop new caring relationships, not only in the sense of sustaining and repairing a world where humans and non-humans may live as well as possible within the same vital network, but also as regards the inclusion of those actors and matters which, until now, have not been successful in articulating their concerns25.

[1] On identification and relation as modes of structuring individual and collective experiences, see Philippe Descola: Más allá de naturaleza y cultura, Amorrortu, Buenos Aires, 2012, pp. 177-179 and 446-447.

[2] A term used in Argentina to refer to someone who uses a horse-drawn cart to collect recyclable material.

[3] The quotes in italics correspond to statements expressed by each agent in interviews, meetings and public speeches, or in documents, blogs, official web pages and pamphlets.

[4] P. Singer: Liberación animal, Taurus, Madrid, 2011, pp. 17-21.

[5] M. Carman and María Valeria Berros: “Ser o no ser un simio con derechos,” in Revista Direito GV vol. 14 N.o 3, 2018.

[6] This conservationist organisation made in 2012 the “Basta de TAS” national tour, aiming to abolish the use of animal-drawn vehicles in Argentina, “based on environmental, animal and human principles”. There are plenty of similar groups, such as the Asociación Contra el Maltrato Animal [Association Against Animal Abuse], the Asociación para la Defensa de los Derechos del Animal [Association for Animal Rights] and the Centro de Rescate y Rehabilitación Equino [Horse Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre].

[7] Elizabeth Lawrence: “Rodeo Horses: The Wild and the Tame”, in Roy Willis (ed.): Signifying Animals: Human Meaning in the Natural World, Routledge, London, 1994.

[8] Unlike sanctuaries —where animals are not visited by the public—, horse healing refuges have a veterinary staff and encourage activists to sponsor an animal. Additionally, they schedule group visits.

[9] Interview with the founder of Proyecto Caballos Libres, 2012.

[10] Interview with an activist, 2015.

[11] J. Butler: Marcos de guerra. Las vidas lloradas, Paidós, Buenos Aires, 2010, p. 51.

[12] Interview with a professional who works at a centre for horse rescue and rehabilitation, 2014.

[13] Interview with the founder of Proyecto Caballos Libres, 2012.

[14] Activist of the group Voluntarios por los Caballos.

[15] Crónica TV programme, 2016.

[16] Cited in Ciméa Barbato Bevilaqua: “Pessoas nao humanas: Sandra, Cecilia e a emergencia de novas formas de existencia jurídica,” in Mana vol. 25 N- 1, 2019, p. 59.

[17] Interview with Bernardo, Padre Mugica residential complex, 2013.

[18] Interview with a veterinary doctor who assists scavengers’ horses, 2013.

[19] P. Descola: op. cit., p. 409.

[20] Ibid., p. 178.

[21] See Émile Durkheim: Las formas elementales de la vida religiosa, FCE, Buenos Aires, 2012; and P. Descola: op. cit., pp. 25-65.

[22] We refer here to the intellectual current developed in the field of anthropology towards the end of the 19th century, influenced by Charles Darwin, and whose foremost exponents were Edward Burnett Tylor and Lewis Morgan. In his ruthless critique, Claude Lévi-Strauss renamed this anthropological current as a pseudo or false evolutionism.

[23] M. Carman: Las trampas de la cultura. Los intrusos y los nuevos usos del barrio de Gardel, Paidós, Buenos Aires, 2006; M. Carman: Las trampas de la naturaleza. Medio ambiente y segregación en Buenos Aires, FCE / Clacso, Buenos Aires, 2011; M. Carman: Las fronteras de lo humano. Cuando la vida humana pierde valor y la vida animal se dignifica, Siglo Veintiuno, Buenos Aires, 2017.

[24] B. de Sousa Santos: Para descolonizar occidente. Más allá del pensamiento abismal, CLACSO, Buenos Aires, 2010. For a deeper analysis on this topic, see M. Carman and M.V. Berros: op. cit.

[25] María Puig de la Bellacasa: “Matters of Care in Technoscience: Assembling Neglected Things,” in Social Studies of Science vol. 41 No 1, 2011, pp. 85-106.

Leave A Comment