Paula Pico Estrada

Libre albedrío, libertad cristiana

y misticismo

en el pensamiento temprano

de Martín Lutero (2020)

Vínculo al texto original:

Libre albedrío, libertad cristiana y misticismo en el pensamiento temprano de Martín Lutero

Vínculo a la primera parte:

San Agustín de Hipona, Gerard Seghers (atr.)

Paula Pico Estrada es doctora en filosofía especializada en filosofía medieval. Es profesora de Historia de la Filosofía Medieval en la Universidad del Salvador y directora de la carrera de Filosofía en la Universidad de San Martín. Entre otros tantos intereses académicos, es una destacada especialista en el pensamiento de Nicolás de Cusa (su obra más reciente, publicada en 2021 por Brill, se titula Nicholas of Cusa on the Trinitarian Structure of the Innate Criterion of Truth). La profesora Pico Estrada también es directora editorial de Ediciones Winograd, editorial independiente dedicada a la difusión de textos filosóficos y de humanidades en general, así como crónicas y relatos de viaje.

Hace unos meses, tuve el agrado de asistir a algunas clases de la profesora Pico Estrada. Entonces comprobé que, además de ser una gran investigadora de la historia de la filosofía, es una docente excelente y una persona sumamente amable. Quise traducir este texto suyo sobre el pensamiento de Martín Lutero no solo por resultarme muy interesante, sino también como un pequeño gesto de agradecimiento hacia ella, por toda la ayuda que me prestó. Para quienes deseen leer otros trabajos suyos, recomiendo visitar su perfil en Academia.edu (salvador.academia.edu/PaulaPicoEstrada).

Free Will, Christian Freedom and Mysticism

in Martin Luther’s Early Thought

2. FREEDOM

2.1 FREEDOM ACCORDING TO SAINT AUGUSTINE

If we collect the Augustinian quotes used by Luther throughout the quaestio, the result will be a doctrinal summary. The precepts of the law cannot be kept without love for God and for the neighbour. This love, called caritas, presupposes faith in Christ and is received by the mercy of God, which no one deserves. Whoever has not received this gift, whoever has not received the grace of hearing about the Christian revelation, shall burn in Hell, even those who keep the precepts of the law. The reason why some receive this saving grace and others do not is beyond our understanding. Our entire capacity regarding good and righteousness, then, comes from God, not only to according to them, but even to think and desire them. Free will is not free to make good but to make evil, which means that, unless it is freed by Freedom, will is bonded. In summary: human beings need grace to be saved, but no one can earn any merit to obtain it because anything made without grace is sin. Does this set of claims mean that neither Augustine nor Martin Luther believed in freedom?

To understand the deeper sense of Luther’s stance in the 1516 quaestio, it is necessary to take into account the Augustinian distinction between free will (liberum arbitrium) and freedom (libertas). Such distinction pervades Augustine’s entire treatment of the matter, from De Libero Arbitrio (388-391) to De Civitate Dei (413-426), including the anti-Pelagian epistles and treatises (approximately between 411 and 429). To avoid expanding too much on this subject, I will choose two passages: one from De Libero Arbitrio (On Free Choice of the Will) and the other from De Civitate Dei (The City of God), i.e., one from his earliest and one from his latest systematic treatises.

As is well known, On Free Choice of the Will is a dialogue between Augustine and an interlocutor called Evodius, who are seeking the answer to a contradiction. If God, supreme goodness, is the Creator of all things, even human will, why is He not responsible for the origin of the evil we commit? The research developed in Book I comprises various stages. One of the first is the realisation that our will makes evil when it is led by the weight of desire towards those things we can lose unwillingly (Augustine uses libidine and cupiditas interchangeably to allude to this kind of desire).[37] Given that one of the examples used is that of killing (as one who kills when his life is threatened, in an attempt to preserve it), and that human law does not punish killing if it is done in self-defence, the discussion turns to the relationship between temporal law and eternal law. It is in this context (paragraph 32 of Chapter 15 from Book I) that Augustine enumerates the temporal goods, freedom among them.

Then, freedom, which is undoubtedly not true unless it resembles that of the blessed and of those who adhere to eternal law: but I do not mean now that freedom whereby those without a lord consider themselves free, likewise desired by those who wish to become free from their human lords.[38]

This passage distinguishes the notion of true freedom from another kind of freedom which implies the possibility to choose, given the absence of compulsion or necessity. This is a key distinction. The second kind of freedom is what is properly called “free will”. As we have seen in the previous section, according to the Augustinian conception, free will always chooses between hierarchically different goods, and although it has been given to us to choose always for the sake of supreme Good and thus attain happiness, which is salvation, the fallen state of our nature makes it impossible to do so without intervening grace. Now, said notion of free will presupposes another dependent notion. This is freedom, the “true freedom” discussed by Augustine in On Free Choice of the Will I.15.32.

True freedom is that which belongs to the blessed and those who obey the eternal law. Although the et used in this short enumeration could be understood as being epexegetic, I have preferred not to overtranslate it, given that this is an early text by Augustine in which he argues against the Manicheans, not the Pelagians. But if, instead, I had translated the phrase as “freedom, which is undoubtedly not true unless it resembles that of the blessed, that is, of those who adhere to eternal law”, I would not have distorted the ultimate sense of the term “freedom” as Saint Augustine understands it. Indeed, true freedom only belongs, strictly speaking, to the blessed, because they are the only ones who can adhere to the eternal law without straying from it. They behold God and their will is no longer attracted by lesser goods; they possess true freedom, which is nothing else than Jesus Christ. In Book II of On Free Choice of the Will, after having identified Truth with Wisdom and established that blessed life consists in contemplating it, Augustine makes a further identification. Truth, which is Wisdom, is true freedom, which is nothing else than Jesus Christ:

This is our freedom, with it we submit to truth: that is, it is our God, Who makes us free from death, which is the state of sin. For Truth itself, It too a man who spoke with men, said to those who believed in it: If ye continue in my word, then are ye my disciples indeed; and ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free. The soul rejoices in nothing freely except for that in which it rejoices safely.[39]

The same conception of freedom appears in one of the final paragraphs of The City of God, where it is also linked to free will:

Not because they [the blessed] cannot delight in sins shall they cease to have free will. On the contrary, this will shall be freer, released from the delight of sinning towards the unwavering delight of not sinning. For the first free will, given to man when he was first created righteous, could abstain from sinning, but could also sin: the new one, however, shall be so much more powerful that it shall not be able to sin. Incidentally, this also comes from God, not from the possibilities of its own nature. Since it is one thing to be God, another to take part in God. God cannot sin by nature, but he who takes part in God receives from Him the impossibility to sin. It was necessary that there should exist degrees in the divine gifts, so that first that free will were given whereby man could avoid sinning, and then the new one, whereby he could no longer sin. The former, to seek merit; the latter, to prize those who deserved it.[40]

This passage makes us understand that free will is human participation in divine Freedom. Given our fallen state, this participation tends to become reduced as we yield to the lure of the lesser goods and to increase as we use those goods as steps towards attaining the supreme Good. It is interesting to note that in this passage written in 425, when the polemic against the Pelagians had already been raging for more than a decade, Augustine does not exclude merit. In any case, free will becomes freedom only in the state of blessedness. Freedom is identified with a free will which cannot sin.

Now, the previous development suggests that what we call “free will” is always —paradoxically— bonded. When human beings are in via, free will is bonded to sin, unless it is freed and assisted by grace. When it finds itself in patria, it is bonded to Truth, and hence finally free. In other words, the only way to obtain freedom is by submitting to the revelation of Jesus Christ. This Augustinian notion of freedom is found, as we shall see, in Theologia Germanica.

The Triumph of Saint Augustine, Claudio Coello

2.2 FREEDOM ACCORDING TO THEOLOGIA GERMANICA

Theologia Germanica —of which the connection with Rhineland theology has been extensively commented (see for example VANNINI 2008, pp. 26-33)— presents the characteristic combination of Neoplatonic and Christian elements discussed in the first section. In Theologia Germanica, God is the fullness which comprehends and includes everything in itself and in its being. All things have their being in Him, because He is the being of all things. Outside of God, there is no true being and the creature proceeds from His fullness just as radiance flows forth from the Sun. Along with this absolute ontological pre-eminence of God comes his unknowability:

What is complete is unknowable, incomprehensible and unspeakable for any creature as creature. Thus it is not fully named, because it is none of this. The creature as creature cannot know it nor comprehend it, name it nor think it.[41]

These two classical notes of Neoplatonism, ontological pre-eminence and unknowability, are accompanied by the notions of procession and return to the source. In fact, for the Frankfurt Anonymous, Adam’s original sin entails a fall in time and matter, and the return of the soul implies a restoration of human nature which is fulfilled only through obedience to Christ.[42]

However, the differences between this basic structure and the complex Dionysian hierarchical system (adding also the idea that Scripture has a hidden sense which must be penetrated) are many. The Neoplatonic traits of Theologia Germanica, just like those of Augustine of Hippo’s philosophy, do not clash with its distinctive feature, which is its Christology. The treatise returns time and again to the need of living Christ’s life, of conforming to his obedience and of foregoing or emptying one’s own will to align it with divine will. The latter point is closely related to the Augustinian conception of freedom shared by Luther.

The guiding thread in Theologia Germanica’s argument is that the Fall, which brought death to mankind, was due to Adam’s disobedience, and that true obedience, that is, Christ’s, resurrects the life which died with Adam. Hence, the path to obtaining life is adhering to true obedience, which means renouncing one’s own will. Freedom lies in this true obedience.

But what is true obedience? I say: that man should remain completely free from himself and his things, that is, free from be-ness and I-ness, so that he may not seek or consider himself and his things in all things, as if he did not exist […] This is true obedience to truth, and so shall it be in blessed eternity. Therein nothing is sought or thought nor loved except for what is one, and nothing is valued except for what is one.[43]

Disobedience, in turn, consists in believing that one is someone who has knowledge and can do things. It does not occur only when we commit the kind of actions commonly reputed as evil, but also when we indulge in our own virtue and think we have attained some state of obedience, which would become manifest —for instance— in a certain temperance of spirit, indifferent to the whims of fortune. The Anonymous is strict:

No, in fact it is not so, it is as previously written; it would be so if all men were in obedience. But this is not so, and hence neither is that so.[44]

The life of Christ is certainly not obtained by listening to sermons, reading or studying. As long as someone clings to himself, he will consider only what suits his own interests to be good.

This attachment to one’s own is what makes it evil to use of free will, an expression avoided by the treatise, which prefers instead the expression “false freedom” (falsche freiheit: VON HINTEN, p. 103). In the origin of disobedience —it is said in Chapter 25— there are two twin fruits born from the seed of evil. One is spiritual pride and the other is false freedom, that is, a disordered freedom (ungeordente, falsche freiheit: VON HINTEN, p. 103). Spiritual pride becomes manifest as an illusory peace arising from self-satisfaction. “The devil breathes into man to make him believe and think that he has reached the highest and nearest point, and that he no longer needs Scripture[45].” This state leads man to believe he is the lord of all creatures and, in summary, to act as he pleases. In terms of the Quaestio de viribus, by using his free will he “subjects any creature he uses to his vanity”. (See the first conclusion, cited in the second section.) Furthermore, the notion of disorder brings to mind the Augustinian conception of evil.

If pride and false freedom are the origins of disobedience, poverty of spirit and true humility are the way towards obedience and, hence, liberation. Said attitudes are proper to the man who knows that he is nothing, that he has nothing and that he is only capable of weakness and evil. These notions of the treatise are not so far from the Saint Augustine who writes in the epistles against the Pelagians: “Why do you defend free will, which is not free to work justice unless you become a sheep?” (cited in the second section). By contrast, the man with a poor and humble spirit, conscious of his own leaning towards evil and sin, correctly understands that his inclination is common to mankind and thus makes customs, laws and precepts necessary.

Besides, in this spiritual poverty and humility, it is understood and found that all men answer to themselves and are inclined and turned towards vice and evil, and that thereby it is necessary and useful to have orders and knowledge, laws and commandments […].[46]

The man who has understood this, the truly humble man, only desires to annihilate himself and become empty of self-will, so that the eternal will may live in him and rule him without any impediment from another will, so that it can be done through him. In God —holds the treatise— the divine will is an essence dissociated from any work and any action; it is the duty of the human creature, then, to translate the divine will into works. This is what we have been created for. The will is not ours, but God’s. If this emptying of the self

came to pass truly and freely in a man, nothing would be desired by the man, but everything by God, and the will would not be his own nor would he wish anything else than what God wishes.[47]

The model of this absolute adherence to the divine will is Christ. Consequently, Christ’s humanity was the freest creature, given that this adherence represents true freedom, which the treatise calls “divine”. The other, which is linked to self-will, is a diabolic and false freedom; in fact, Hell is characteristically inhabited by self-wills. In turn, “what is free does not belong to anyone, and he who makes it his own commits an iniquity” (was frey ist, das ist nymants eigen, und wer den eygen macht, der thut unrecht: VON HINTEN, p.145). In line with this conception, the description of Paradise brings again to mind some notions expressed by Saint Augustine, in this case, in the final paragraphs from The City of God, cited in the previous section. For Theologia Germanica, blessedness consists in setting the will free, that is, emptying it from any self-desire so that it may become complete with the eternal will.

But he who leaves his will in its free condition obtains satisfaction, peace, blessedness, in time and in eternity. If man does not make will his own, but preserves it in its noble freedom, he becomes and is a true man, free, unbound, the creature of which Christ says “Truth shall make you free”; and immediately after: “If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed”.[48]

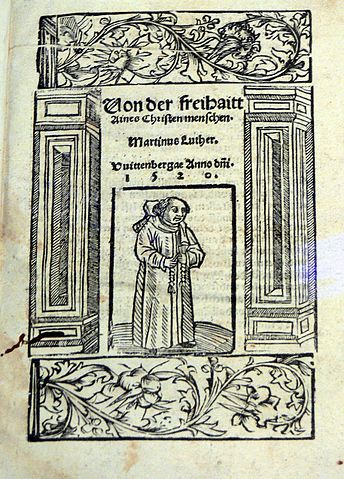

2.3 FREEDOM ACCORDING TO ON THE FREEDOM OF A CHRISTIAN

10 December 1520 was the deadline fixed by Pope Leo X in his bull Exsurge Domine for Luther to recant from a set of propositions. The Reformer’s tacit answer was three treatises, written and published between June and November that year: On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, To the Christian Nobility of a German Nation and On the Freedom of a Christian. Known as “the writings of the Reformation”, they laid the theological and political foundations of the new Church. Far from the bitter diatribes characteristic of the other two opuscules, On the Freedom of a Christian is a text in which Luther expresses himself with unusual sweetness, still influenced by Theologia Germanica. (A new edition of the latter appeared in 1520, including commentaries in German, possibly by Luther himself. If this were the case, it would prove that he was still revising the text by that year.)

On the Freedom of a Christian is a text deliberately built upon two contradictory statements traced by Luther to Saint Paul (1 Cor. 9, Rom. 13, Gal. 4, Phil. 2:6-7). The first is “The Christian is a free man, lord of everything and not subject to anyone”; the second is “The Christian is a slave [servus], at the service of everything and subject to everyone”. Together they constitute a paradox which Luther intends to defend, so that we may fully know what it means to be a Christian and “how one must act with regards to the freedom which Christ has conquered and given”. That is, the contradiction is solved if we understand what is the particularly Christian freedom. We need not delve into the text to foresee that Luther will put forward —just like Saint Augustine and Theologia Germanica— that free will or self-will must become the slave of the divine will to attain freedom.

Once established these theses, Luther refers respectively to the two natures proper of a Christian, the spiritual and the bodily. So, this very short treatise is divided into two sections: one dedicated to the spiritual or inner man, and the other to the bodily or external man. It is evident —he argues— that nothing external can justify the inner man or make him free, since neither his goodness and freedom nor his wickedness and captivity are bodily realities. This simple claim conceals a criticism of the teaching that good works may afford merit, and that this merit is significant in terms of salvation. Afterwards, Luther makes it explicit:

None of these things is pertinent to the freedom or slavery of the soul. Thereby, it will be of no benefit whatsoever if the body is adorned with sacred vestments, in the manner of the consecrated, or if it proceeds towards sacred places or looks after the sacred offices or prays, fasts or abstains from certain foods and does some work through the body or which could be made in the body: very different are the works necessary to attain a righteous and free soul, given that what has been said could well be performed by any impious man, and applying these things yields nothing but hypocrites.[49]

Nothing makes the soul righteous, free and Christian but the Word of God. Anything else is dispensable. This Word is no other than the Gospel preached by Christ, but to accept it, it is necessary to have experienced that our life and works mean nothing before God. This is the purpose of the Law imposed by the Old Testament, i.e., making humankind humble due to the impossibility of keeping it. The idea is key in Luther’s intellectual revolution between 1517 and 1520: the sheer humiliation brought about by experiencing the impossibility of keeping the law leads to a surrendering of self-will, which can only be achieved through faith in the Word of the Gospel (see his own account in LUTHER WT 2, p. 1681). “There is only one thing which counts as works for Christian life, righteousness and freedom. It is the sacrosanct Word of God, the Gospel of Christ.”[50]

Luther appeals to the aforementioned idea to reconcile his teaching that only faith justifies with the fact that in Scripture there are multiple laws and commandments: the sole aim of the law is to make evident for human beings their powerlessness for good, compelling them to learn not to trust in themselves and to seek help elsewhere to keep the commandments and thus avoid eternal damnation. And so, when man “has truly humiliated himself, has annihilated himself before his own eyes, and finds nothing in himself by which he may be justified and saved”[51], there arrives help through the divine promise that grace, justification, peace and freedom are given in Christ.

This way, only through faith, without works, by the Word of God, the soul is made righteous, holy, true, peaceful, free, and abundant in every good, and fulfilled as a true daughter of God, as says John, 1:12: “But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name”.[52]

Now, does this freedom, resulting from the complete annihilation of self-will and the adherence to the Gospel through faith, imply that the human being thus liberated is separated from the world? This is the perspective which the reader may expect to find in the second section of the treatise, where Luther discusses the treatment of the external man. The foreseeable conclusion, in fact, would be that if the inner man, justified by faith, is free, then the external man, being chained to the weight of the body, is a slave. However, this is not what the author says. The external man’s slavery is not the slavery of sin, but that of serving the neighbour.

Thus, the second section is divided into two parts. The first part is dedicated to the works needed to temper the bodily appetites. Luther is not going back here regarding his conviction that only faith in the divine Word justifies, but rather understands that these works depend on faith. It is faith which makes works good, and if they were done without faith, they would have no value whatsoever. The second part deals with the works which must be done regarding others. The reasoning is similar to the previous part, and the message is summarised by the idea that the sole intent of all works should be to serve others; the neighbour’s needs are the only aim (LUTHER, WA 7, p. 64). As we can see, the second section shows that the two contradictory statements at the beginning of the treatise may be united in a single one: precisely because the Christian is free and is no longer bound to anything, he can and must be a slave to all. Thus, the treatise On the Freedom of a Christian completes the 1516 Disputatio, incorporating the then-used notion of free will to the notion of freedom on which it depends. Both ideas belong to Augustine of Hippo.

First German edition of On the freedom of a Christian

CONCLUSION

The aim of this article was to investigate the reasons behind Luther’s sustained interest in Theologia Germanica in 1520. Indeed, that same year the Reformer published two treatises which we might be inclined to consider incongruous. In The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, he accuses the Pseudo-Dionysius of being more Platonist than Christian. At the same time, the notion of freedom displayed in On the Freedom of a Christian is indebted to the developments of Theologia Germanica, a treatise where we can discern, as in a large part of the Christian mystical literature, the traces of the Neoplatonist tradition. In this article, we argued that the apparent incongruence can be solved if, on the one side, we acknowledge that the notion of freedom in Theologia Germanica evinces the influence of Augustine of Hippo, and, on the other side, we prove the dependence of the Lutheran notions of free will and freedom on Augustinian thought. With that aim in mind, the article was divided into two sections: one dedicated to the notion of free will and the other to the notion of freedom.

Hence, in the first section we analysed the disputed question On the Power and Will of Man Apart from Grace and demonstrated the textual dependence of its arguments on many anti-Pelagian works by Saint Augustine. In the second section, we explained first the Augustinian concept of free will, which cannot be properly understood in isolation from the concept of freedom. Then, we compared the similarities between the Augustinian concept of freedom and the concept of mystical freedom which permeates the treatise Theologia Germanica. Finally, we showed the presence of this very concept in On the Freedom of a Christian. Thus, we achieved the objective of answering the question of Luther’s persistent interest in the anonymous treatise. His theoretical speculation regarding the freeness of will and grace, which led him to condemn the 1517 indulgences campaign, is linked to the notion of freedom as an emptying of the self, which, in 1520, formed the basis of On the Freedom of a Christian, a key text of the Reformation.

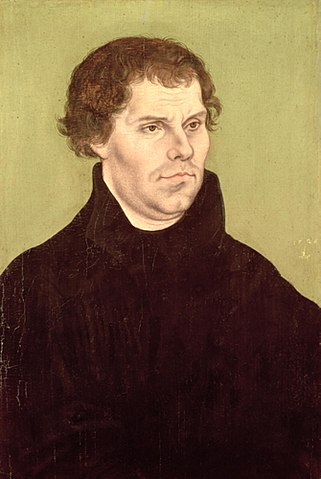

Portrait of Martin Luther, Lucas Cranach the Elder

NOTAS

[37] AUGUSTINUS, De Libero Arbitrio I.4.10: Cupere namque sine metu vivere, non tantum bonorum, sed etiam malorum omnium est: verum hoc interest, quod id boni appetunt avertendo amorem ab iis rebus, quae sine amittendi periculo nequeunt haberi; mali autem ut his fruendis cum securitate incuhent, removere impedimenta conantur. et propterea facinorosam sceleratamque vitam, quae mor melius vocatur, gerunt.

[38] AUGUSTINUS, De Libero Arbitrio I.15.32: “Deinde libertas, quae quidem nulla vera est, nisi beatorum, et legi aeternae adhaerentium: sed eam nunc libertatem commemoro, qua se liberos putant qui dominos homines non habent, et quam desiderant ii qui a dominis hominibus manumitti volunt.”

[39] AUGUSTINUS, De Libero Arbitrio II.13.37: “Haec est libertas nostra, cum iste subdimur veritati: et ipse est Deus noster qui nos liberat a morte, id est a conditione peccati. Ipsa enim Veritas etiam homo cum hominibus loquens, ait credentibus sibi: Si manseritis in verbo meo, vere discipuli mei estis, et cognoscetis veritatem, et veritas liberabit vos. Nulla enim re fruitur anima cum libertate, nisi qua fruitur cum securitate.”

[40] AUGUSTINUS, De Civitate Dei XXII.30.3: “Nec ideo liberum arbitrium non habebunt, quia peccata eos delectare non poterunt. Magis quippe erit liberum a delectatione peccandi usque ad delectationem non peccandi indeclinabilem liberatum. Nam primum liberum arbitrium, quod homini datum est, quando primum creatus est rectus, potuit non peccare, sed potuit et peccare: hoc autem novissimum, eo potentius erit, quo peccare non potuit; verum hoc quoque Dei munere, non suae possibilitate naturae. Aliud est enim esse Deum; aliud participem Dei. Deus natura peccare non potest; particeps vero Dei ab illo accipit, ut peccare non possit. Servandi autem gradus erant divini muneris, ut primum daretur liberum arbitrium, quo non peccare homo posset, novissimum, quo peccare non posset, atque illud ad comparandum meritum, hoc ad recipiendum praemium pertineret.”

[41] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter.(Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum I, pp. 71-72: “Das volkommende ist allen creaturen vnbekentlich, vnbegrifflich vnd vnsprechlich yn dem als creatur. Dar vmmb nennet man das volkommende nicht, wann eß ist disßer keyns. Die creatur als creatur magk diß nicht bekennen noch begriffen, genennen noch gedencken.”

[42] Cfr., for example, cc. 11-16. The subject, however, permeates the entire treatise.

[43] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum 15, p. 89: “Was ist aber war gehorsam? Ich sprech: Der mensch solde also gar an sich selber steen vnd seyn, das ist, an selbheit vnd icheit, das er sich vnd das seyne also wenig suchte vnd meynete yn allen dingen, also ab er nicht were, noch seyne selbs als wenig entpfinden vnd von ym selbir vnd dem seynen also cleyne halden, also er nicht were, vnd als wenig von ym selber alß wenig von allen creaturen. Was ist danne das, daz do ist vnd da von zu halden ist? Ich sprich: alleyne eynes, das man got nennet. Sich, das ist war gehorsam yn der warheit vnd also ist eß yn der seligen ewikeit. Danne wirt nicht gesucht noch gemeynet ader gelibt danne das eyne, so wirt auch von nichte gehalden denne von dem eynen.”

[44] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum 17, p. 94: “Neyn czwar, ym ist nicht also; ym ist, als *vor geschriben ist; ym were wol also, weren alle menschen yn dem gehorsam. Aber nu ist eß nicht also, dar vmmb ist auch diß nicht alßo.”

[45] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum 25, p.103: “Der teufel bleßet dem menschen yn, das den so menschen duncket vnd wenet, er sey uff das hochste vnde uff das nehste kom men vnd durffe wider schrifft noch diß noch daß furbas mer vnd sey joch czumal durffloß wurden.”

[46] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum 26, p.106: “Auch wirt yn dißem geistlichen armut vnd demutikeit vorstanden vnd funden, das alle menschen kummen czumäl auff sich selber vnd joch uff vntogent vnde boßheit geneyget vnd gekeret seyn, vnnd das dar vmmb not vnd nutze ist, das ordenung vnd wiße vnd gesetze vnd gebot sint, das die blintheit da mit geleret werde vnd boßheit geczwungen werde czu ordenlicheit. Vnd were des nicht, die menschen worden vil boßer vnd vnordenlicher dan hund ader ander vihe. Vnd wirt auch manig mensch durch diße weiße vnnd ordenunge geczogen vnd gekeret czu der warheit, das anders nicht geschee.”

[47] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum 51, p.145: “Und wo das luterlich vnd gentzlich were ader 45 yn welchem menschen da wurde gewold nicht von dem menschen, sunder von got, vnd da were der wille nicht eygen wille vnd da wurde auch nicht anders gewold, den als got wil.”

[48] VON HINTEN, Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch), Capitulum 51, p.146: “Aber wer den willen yn seyner freyen art lesset, der hat genuge, fride, ruwe, selikeit yn der czeit vnd yn ewikeit. Wo vnd yn welchem menschen der wille nicht geeygent wirt, sundern das er bleibet yn seyner edeln freiheit, da wirt vnd ist eyn ware, frey, ledig mensch adder creatur, da von Cristus spricht : >Die warheit sal uch frey machen<, vnnd czuhant dar nach: >Wen der sone frey macht, der ist werlich frey<.

[49] LUTHER, Tractatus de Libertate Christiana. WA 7, p. 50. “Neutra harum rerum pertingit ad animae sive libertatem sive servitutem. Ita nihil profuerit, si corpus sacris vestibus more sacrorum ornetur aut locis sacris versetur aut officiis sacris occupetur aut oret, ieiunet, aut abstineat certis cibis et faciat opus quodcunque per corpus et in corpore fieri potest: longe alia re opus erit ad iustitiam et libertatem animae, cum ea quae dicta sunt geri possint a quovis irapio nee hiis studiis alii quam hypocritae evadant.”

[50] LUTHER, Tractatus de Libertate Christiana. WA 7, p. 50. “Una re eaque sola opus est ad vitam, iustitiam et libertatem Christianam. Ea est sacrosanctum verbum dei, Euangelium Christi.”

[51] LUTHER, Tractatus de Libertate Christiana. WA 7, pp. 52-53: “Ubi vero per praecepta doctus fuerit impotentiam suam et iam anxius factus, quo studio legi satisfaciat, cum legi satisfieri oporteat, ut ne iota quidem aut apex praetereat (alioquin sine ulla spe clamnabitur), tum vere humiliatus et in nihilum redactus coram oculis suis uon iuvenit iu seipso, quo iustiticetur et salvus fiat.”

[52] LUTHER, Tractatus de Libertate Christiana. WA 7, p. 53: “Hoc igitur modo anima per fidem solam, sine operibus, e verbo dei iustificatur, sauctificatur, verificatur, pacificatur, liberatur et omni bono repletur vereque filia dei efficitur, sicut Iohan. 1. Dicit ‘Dedit eis potestatem filios dei fieri, iis qui credunt in nomine eius’.”

REFERENCES

ANONIMO FRANCOFORTESE. Teologia Tedesca. Libretto della vita perfetta. A cura di Marco Vannini. Milan: Bompiani, 2009.

ANONYMOUS, Eyn geystlich edles Buchleynn von rechter vnderscheyd vnd vorstand was der alt vn new mensche sey. Was Adams/ vn was gottis kind sey. vn wie Adä lynn vns sterben vnnd Christus ersteen sall. Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, 1516.

ANONYMOUS, Eyn deutsch Theologia, das ist eyn edles Buchleyn von rechtem vorstand was Adam vnd Christus sey vnd wie Adam yn vns sterben vnd Christus ersteen sall. Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, 1518.

ANONYME DE FRANCFORT. Le petit livre de la vie parfaite. Traducteur: Gérard Pfister, préfacier: Alain de Libera. Orbey: Arfuyen, 2000.

ANONYMOUS, The Book of the Perfect Life: Theologia Deutsch — Theologia Germanica. Introduction and translation, David Blamires. Walnut Creek, California: Alta Mira Press, 2003.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, De spiritu et littera, eds. K. Urba & J. Zycha, CSEL 60, 1913.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Contra duas epistolas Pelagianorum, eds. K. Urba & J. Zycha, CSEL 60, 1913.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Epistulae ad Galatas expositio, ed. J. Divjak, CSEL 84, 1971.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Enchiridion ad Laurentium de fide, spe, et caritate, ed. 1969 Evans, CCSL 46, 1969.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Contra Iulianum, PL 44.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Contra Iulianum opus imperfectum, PL 45.

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, De gratia et libero arbitrio, PL 44.

BACKUS, Irena and GOUDRIAAN, Aza. “‘Semipelagianism’: The Origins of the Term and its Passage into the History of Heresy”, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 65, No. I (January 2004), 25-46.

BELLINI, Enzo. Introduzione en DIONIGI AREOPAGITA, Tutte le opere, traduzione di PIERO

SCAZZOSO. Milan: Rusconi, 1981.

ECK, Johann, Enchiridion locorum communium adversus Lutheranos et alios hostes ecclesiae (1525-1543). Mit den Zusätzen von Tilman Smeling o.p. (1529-1532). Herausgegeben von Pierre Fraenkel. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1979.

HAAS, Aloyse. Der Franckforter: Theologia Deutsch. Einsiedeln: Johannes Verlag, 1993.

HENRY, Paul. La vision d’Ostie. Sa place dans la Vie et l’Oeuvre de saint Augustin. Paris: Vrin, 1938.

LUTHER, Martin. La cautividad babilónica de la Iglesia (1520) in WA 6:562. Translation [into Spanish] by Rodolfo Obermüller in Obras de Martín Lutero. Tomo I. Buenos Aires: El escudo – Paidós, 1967.

LUTHER, Martin. D. Martin Luthers Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe. 73 vols. Weimar: Herman Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1883-2009.

MANDOUZE, André. L’écxtase d’Ostie: Possibilités et limites de la méthode des paralleles texuels in Augustinus Magister, vol. I. Paris: Études Augustiniennes, 1954.

MCGINN, Bernard. The Harvest of Mysticism in Medieval Germany (1300-1500). Vol. IV of The Presence of God: A History of Western Christian Mysticism. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2005.

MCGINN, Bernard. Mysticism in the Reformation (1500-1650). Vol. VI, Part One of The Presence of God: A History of Western Christian Mysticism. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2016.

VON HINTEN, Wolfgang. Der Franckforter (Theologia Deutsch): Kritische Ausgabe. Munich: Artemis, 1982.

Leave A Comment