Commentary on the translation of

“Metaphysics and

the Philosophy of Mind”,

G. E. M. Anscombe

Link to the original text:

Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind

Link to part I:

Link to part II:

Link to part III:

G.E.M. Anscombe: “Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind” (1981), chapter 3: Substance (III)

Somerville College, Oxford

Translating Elizabeth Anscombe is so difficult! Honestly, I could not come up with anything else to say to begin writing about it. During the past weeks, I posted in three parts the translation of chapters 1 and 3 of her book Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind (1981), but actually, I had translated them more than a year ago. In fact, those were among the first translations I undertook, once I had conceived the idea of this blog. Then as well as now, upon revising them, I get a feeling of uncertainty (insecurity?) upon asking myself whether I truly understood what she meant to say, whether my translation truly expresses what she meant to express. (By the way, upon revising more than a year later, I found many things to correct and clarify; I take it as auspicious: I must have learnt something…)

Such self-imposed effort makes me think that this time, before delving into how to translate Elizabeth Anscombe, it is necessary to ask: why translate Elizabeth Anscombe? It does not seem difficult to answer. After all, Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe (1919-2001) is one of the most prominent figures of 20th century thought, a brilliant philosopher who became an unquestionable landmark in the development of Analytic philosophy, but also in the revival of ancient (I dare say, perennial) theories, such as virtue ethics. As is well-known, she was the only female student of the great Ludwig Wittgenstein, with whom she always kept a close relationship, holding mutual intellectual and personal respect. So much so that, before dying, the Austrian asked her (and American philosopher Rush Rhees) to edit and translate into English his unpublished writings, among them no more and no less a work as Philosophical Investigations.

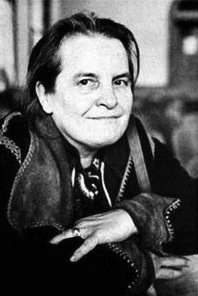

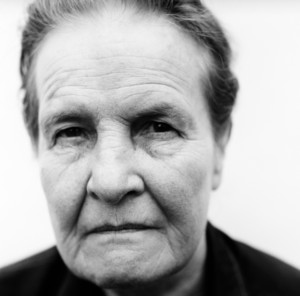

However, Elizabeth Anscombe was never content to be “the disciple of”; on the contrary, she characteristically always held very personal and strong opinions, even opposing the dominant views in the academia of her (and our) age. An example of this would be so famous an essay as Modern Moral Philosophy. We should not leave aside the fact that she grew and flourished at a time when the place of women in philosophy was yet much further than today from being equal. But she paid attention to none of that. Looking at any photograph of the elder Anscombe makes me feel just like I do when reading her writings: I see a stern woman, with a penetrating gaze, and a rocky intellectual solidity (but not rigidity). She is a person whose appearance says nothing extraordinary and, at the same time, says everything; we regard a woman who is both simple and imposing in her humanity. She is strict, indeed; she conveys that feeling even while smiling. And yet, behind that strictness she conceals the warm assurance that her whole thought is devoted to unravelling that truth which may allow the human being to develop his full goodness, to pursue that εύδαιμονία Aristotle referred to.

Academic and intellectual reasons to translate Anscombe are abundant. We should add that she is not precisely a “forgotten” author at all: in the Anglosphere, her stature and influence are well-recognised; meanwhile, within the sphere of Continental philosophy, although perhaps not with as much impact as in her own language, many of her works have been translated into various languages. Spanish, indeed, is not an exception. Therefore, maybe I should redefine my question: why did I translate Elizabeth Anscombe? Well, the most obvious answer would be that this work in particular, Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind, has not been translated into Spanish (as far as I know). The second answer, as obvious as the first, would be that I thought it was an interesting text, period; as I have already explained elsewhere, the only aim of this page is sharing interesting and mind-nourishing works.

A less schematic, but perhaps more precise answer is to be found in my personal experience. The truth is that Elizabeth Anscombe, for most of us, is not a household name. I am not a philosophy scholar (saying philosopher would be pretentious), even less a philosophy professor (I lack any kind of formal studies in this field), and I could at best consider myself an (attentive) reader of philosophy. Thus, it may be that the invisibility I sense regarding her figure is a consequence of my deficiency in this matter. My intuition, however, makes me hear an undesirable dissonance between the sheer importance of Anscombe’s intellectual work and the scarce attention she gets within the academia —not to mention general thought. This is question-begging. Actually, I confess to being unable to answer such a question. To be sure, even a superficial reading of her writings will make us see that her philosophical views are very different from the dominant views in the most prominent intelligentsia of our days. The sharpest contrast would undoubtedly be in the sphere of ethics. In my opinion, this mere divergence of opinion should not be reason enough to explain her absence, even more so in an environment which boasts of advocating diversity.

Nevertheless, as I said, It is not my place to give an answer to such a question, as much as it is not my place to analyse the content of Anscombe’s work; furthermore, it is worth remembering that the articles I translate do not necessarily reflect my own views on the topics at hand, nor my adherence to their authors’ thought. What is important here is that this great thinker’s work is not even close to holding the place it truly deserves. After all, this is more than enough reason to have chosen to translate this text of hers. The true question, in the end, should be: who would not like to translate Elizabeth Anscombe?

I do not intend to ignore the reason why I chose to introduce this commentary with such an exclamation as I did. As anyone who has ever engaged with any of her works may attest, reading Anscombe poses a genuine challenge. It is not easy at all to keep up with someone who has such a degree of depth in her analysis. We must also admit that her tendency to leave the conclusions she wants to reach unexplained (I would almost say, hidden) is a peculiar feature which adds to that feeling of having slipped into a labyrinth. Admittedly, we should not leave aside the fact that the topics discussed are in themselves difficult. Reading the titles of chapters 1 and 3 is enough: “The Intentionality of Sensation” and “Substance”. Now, that is frightening! In my case, when I approached these chapters for the first time, a single reading was not enough to understand.

My impression is that the image which most faithfully represents these writings by Anscombe is that of a puzzle. Her text is not structured incrementally, like a building developing from a modest foundation, around a guiding thread; instead, it resembles a series of disjunct pieces which give a glimpse of an image. Perhaps such a structure owes to the method of Analytic philosophy: Anscombe’s aim is to decompose the key terms in the study of metaphysics and the philosophies of mind and perception (“intentionality”, “sensation”, “object”, “substance”, etc.), so as to find what they truly conceal. At the same time, she presents different conceptions about what each of these terms represents —take for instance the distinction between what Ancient philosophy understands by “object”, with what Modern philosophy understands by “object”.

However, the most striking feature of these texts is the apparent absence of conclusions. In the course of reading, you get a feeling of discovering first a piece, then another, then struggling to put these pieces together before discovering yet another piece. All of this not to mention that the pieces Anscombe offers the reader are mostly obtained after an immense effort of intellectual penetration. And just when you are expecting a conclusion which may put all of the puzzle pieces in their place, the text comes to an end. It is as though her intention was to leave such work to the reader: she only presents the tools and the instructions.

All these features, absolutely fascinating, indeed, are what make the stage of understanding so difficult. Without any doubt, when engaging with such a highly complex text as this, it is imperative for the translator to be familiar with the specific terminology; but it is also necessary to be willing to reflect upon the meaning of certain terms —even everyday ones— which, following the philosopher’s analysis, we should not take for granted. Once again, I take as an example the conceptions about the word “object”. In chapter 1, our attention is called to the diversity of meanings which can be given to such term; but, more importantly, to the metaphysical assumptions each of those meanings implies. Understanding the “object” as something which always bears on intention, as the Ancients do, is a whole different world from understanding it as an individual thing, as the Moderns do!

Regarding the stage of expression, the general fragmentary quality often seems to pervade Anscombe’s grammar. That is why some sentences may be confusing, whether they are semantically or grammatically complex, or because they show an apparent disconnectedness with previous sentences. In this sense, it is mandatory to know the content of the author’s arguments and paying much attention to the sense of the terms used, according to her analysis. Let me show an example. Take the following sentence: “When Descartes said that the cause of an idea must have at least as much formal reality as the idea had objective reality, he meant that the cause must have at least as much to it as what the idea was of would have, if what the idea was of actually existed.” Undoubtedly, a syntactically and semantically complex statement; in my case, at least, it was necessary more than a single reading to understand and replicate it. First of all, I had to apply a very detailed syntagmatic analysis to understand constructions such as “what the idea was of would have” within the whole context. Secondly, even once defined the syntagmas, how should we understand what she means by “he meant that the cause must have at least as much to it as what the idea was of would have”? Had I translated literally, I would have written something like “quería decir que la causa debía tener en sí al menos tanto como aquello de lo que era la idea”. In my opinion, an unsatisfactory result, for it is not at all clear what the cause “tiene en sí”. To be sure, the original text is not so evident about it either.

To reproduce Anscombe’s claim, my translation should answer the following question: what does the cause must have to it, according to the author’s explanation of Descartes’ theory? Well, my proposal was this: “quería decir que la causa debía tener al menos tanto sustento como aquello de lo que era la idea”. Why “sustento”, a word the author mentions not? Since Anscombe’s aim in this passage is to explore the old concept of “object”, which used to imply an intentional aspect (that is, the object is not understood as an individual thing, but as an “object of”), her approach is to explain Descartes’ statement in light of such conception. Both the formal reality of causes and the objective reality of ideas, then, cannot exist if not by means of something they are based on, “algo que las sustente” (literally, something which sustains them). Hence my choice.

Certainly, I think that having intervened so upon the text is having taken a considerable risk. On the one hand, I am in danger of compromising as vital a value as the translator’s invisibility (“not saying anything the original says not”). On the other hand, I also place myself in a situation quite open to mistakes. Is that what she truly meant? Would not that be excessive in interpretation? Even if it my interpretation was correct, is “sustento” the appropriate word? Numerous are the doubts in this respect…

No wonder I chose to begin writing about Elizabeth Anscombe’s translation with such an exclamation. And yet, after all, in spite of any uncertainty, something I have no doubts about is the immense value these texts have. They are edifying, illuminating, profound; they are everything that prompts me day after day to carry on, to keep finding new ways to travel in life. After beginning this text with a complaint, this thinker deserves me to conclude it thus: translating Elizabeth Anscombe is so gratifying!

Leave A Comment